- Name

- Roberto Molar Candanosa

- rmolarc1@jh.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-0258

- Cell phone

- 443-938-1944

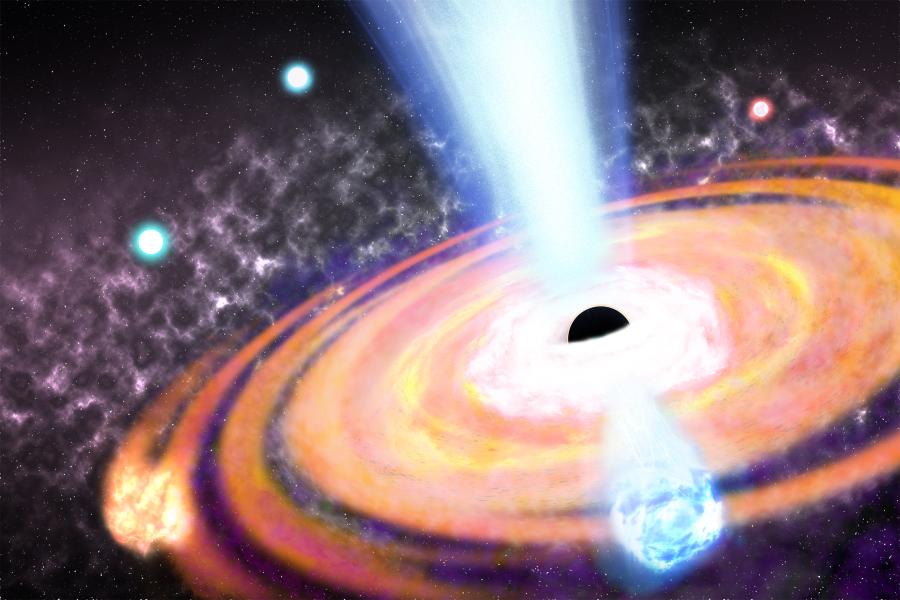

Black holes not only existed at the dawn of time, they birthed new stars and supercharged galaxy formation, a new analysis of James Webb Space Telescope data suggests.

The insights upend theories of how black holes shape the cosmos, challenging classical understanding that they formed after the first stars and galaxies emerged. Instead, black holes might have dramatically accelerated the birth of new stars during the first 50 million years of the universe, a fleeting period within its 13.8 billion-year history.

"We know these monster black holes exist at the center of galaxies near our Milky Way, but the big surprise now is that they were present at the beginning of the universe as well and were almost like building blocks or seeds for early galaxies," said lead author Joseph Silk, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins University and at Institute of Astrophysics, Paris, Sorbonne University. "They really boosted everything, like gigantic amplifiers of star formation, which is a whole turnaround of what we thought possible before—so much so that this could completely shake up our understanding of how galaxies form."

The work is newly published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Distant galaxies from the very early universe, observed through the Webb telescope, appear much brighter than scientists predicted and reveal unusually high numbers of young stars and supermassive black holes, Silk said.

Conventional wisdom holds that black holes formed after the collapse of supermassive stars and that galaxies formed after the first stars lit up the dark early universe. But the analysis by Silk's team suggests that black holes and galaxies coexisted and influenced each other's fate during the first 100 million years. If the entire history of the universe were a 12-month calendar, those years would be like the first days of January, Silk said.

"We're arguing that black hole outflows crushed gas clouds, turning them into stars and greatly accelerating the rate of star formation," Silk said. "Otherwise, it's very hard to understand where these bright galaxies came from because they're typically smaller in the early universe. Why on earth should they be making stars so rapidly?"

Black holes are regions in space where gravity is so strong that nothing can escape their pull, not even light. Because of this force, they generate powerful magnetic fields that make violent storms, ejecting turbulent plasma and ultimately acting like enormous particle accelerators, Silk said. This process, he said, is likely why Webb's detectors have spotted more of these black holes and bright galaxies than scientists anticipated.

"We can't quite see these violent winds or jets far, far away, but we know they must be present because we see many black holes early on in the universe," Silk explained. "These enormous winds coming from the black holes crush nearby gas clouds and turn them into stars. That's the missing link that explains why these first galaxies are so much brighter than we expected."

Silk's team predicts the young universe had two phases. During the first phase, high-speed outflows from black holes accelerated star formation, and then, in a second phase, the outflows slowed down. A few hundred million years after the big bang, gas clouds collapsed because of supermassive black hole magnetic storms, and new stars were born at a rate far exceeding that observed billions of years later in normal galaxies, Silk said. The creation of stars slowed down because these powerful outflows transitioned into a state of energy conservation, he said, reducing the gas available to form stars in galaxies.

"We thought that in the beginning, galaxies formed when a giant gas cloud collapsed," Silk explained. "The big surprise is that there was a seed in the middle of that cloud—a big black hole—and that helped rapidly turn the inner part of that cloud into stars at a rate much greater than we ever expected. And so the first galaxies are incredibly bright."

The team expects future Webb telescope observations, with more precise counts of stars and supermassive black holes in the early universe, will help confirm their calculations. Silk expects these observations will also help scientists piece together more clues about the evolution of the universe.

"The big question is, what were our beginnings? The sun is one star in 100 billion in the Milky Way galaxy, and there's a massive black hole sitting in the middle, too. What's the connection between the two?" he said. "Within a year we'll have so much better data, and a lot of our questions will begin to get answers."

Authors include Colin Norman and Rosemary F. G. Wyse of Johns Hopkins; Mitchell C. Begelman of University of Colorado and National Institute of Standards and Technology; and Adi Nusser of the Israel Institute of Technology.

The team is supported by the Israel Science Foundation and the Asher Space Research Institute, as well as Eric and Wendy Schmidt by recommendation of the Schmidt Futures program.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged astronomy, astrophysics, black holes, physics and astronomy