Scientists across the Johns Hopkins enterprise have begun reopening laboratories after a university order in mid-March shut down nearly all research operations to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. As of June 15, laboratories were permitted to reopen with approved plans that reduce capacity and improve cleaning protocols. But as research resumes in a phased approach, these scientists are learning that returning to the lab doesn't quite mean a return to business as usual.

"Overall, the research community is excited to go back to work, but understandably everyone is concerned about doing so safely," says Denis Wirtz, a cancer researcher and vice provost for research at Johns Hopkins. "There is widespread awareness of new safety precautions, but as we return, we're also identifying new areas to improve safety and limit interactions between people. It's a process that's new for everyone, and we're being adaptive and adjusting our practices accordingly."

In order for research facilities to be reopened, individual departments must prepare and submit for review operating plans that establish new safety protocols and strategies for reducing traffic within buildings and lab spaces. In some cases, that means reducing the number of researchers working at a given time, or creating a rotating schedule if the space can only safely accommodate one person at a time. Department proposals are reviewed by a dedicated restart committee and approved on a rolling basis. Procedures are consistent with federal and state guidance. Undergraduate researchers are not returning at this time.

In Stephen Fried's chemistry lab in Remsen Hall, the new safety protocols mean only four of his seven graduate researchers can work at a time, and the team completes their data analysis work from home. Fried and one of his graduate assistants, Qi Xie, had a bit of head start in returning to their lab as they began working on a new RNA investigation related to the coronavirus. The rest of Fried's group returned last week.

"The concern, under these conditions, is distributing the resource of time equitably," Fried says. "One of the major core values of the restart committee is equity—not prioritizing projects or playing favorites, because every project is important to the grad student who is working on it. So I consider myself quite lucky to have a small team that can coordinate time efficiently so everyone has a chance to spend time in the lab."

The question of equity is especially important to budding scientists, for whom time spent working in a lab is valuable experience. Organic chemist Rebekka Klausen, whose laboratory is also in Remsen Hall, has had to split her team in half in order to resume their research on applying the principles of organic chemistry to create new types of sustainable materials. One of her concerns is maintaining a culture of collaboration among her group while also observing social distancing.

"I have some grad students who only joined the group in January, so they're still integrating with the team," Klausen says. "How do I reimagine the ways the team interacts in the lab? How do I create that team spirit? They have group lunches together over Zoom, but these are some of the questions that contribute to my feeling of trepidation."

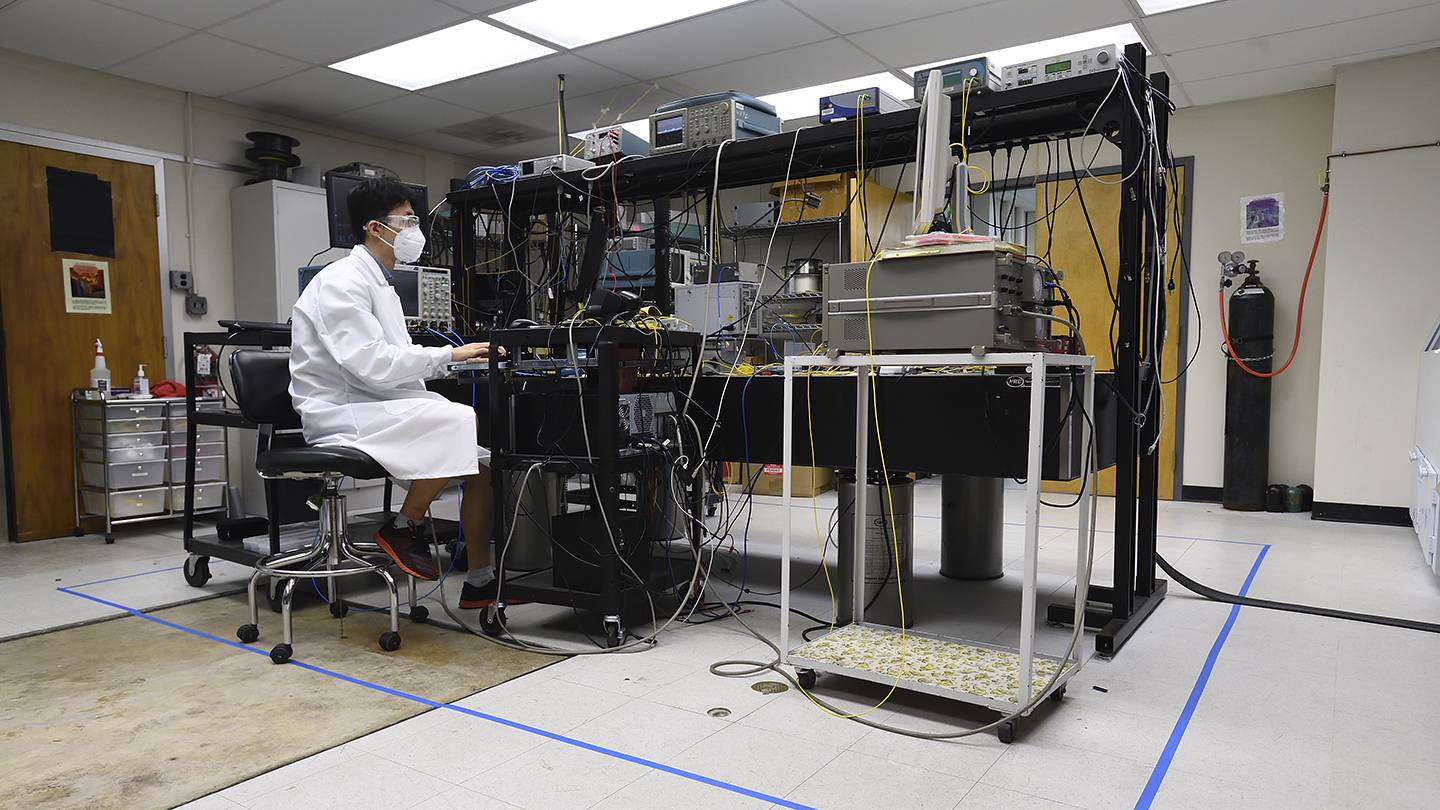

Image caption: Ruidong Xue, a graduate student in Amy Foster's Electrical and Computer Engineering lab, resumes research in June, 2020. On the floor of the lab, blue tape outlines new boundaries for researchers within the lab space.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

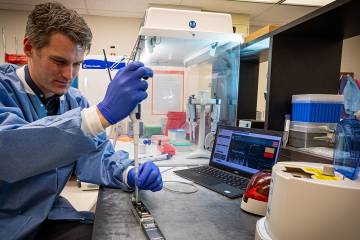

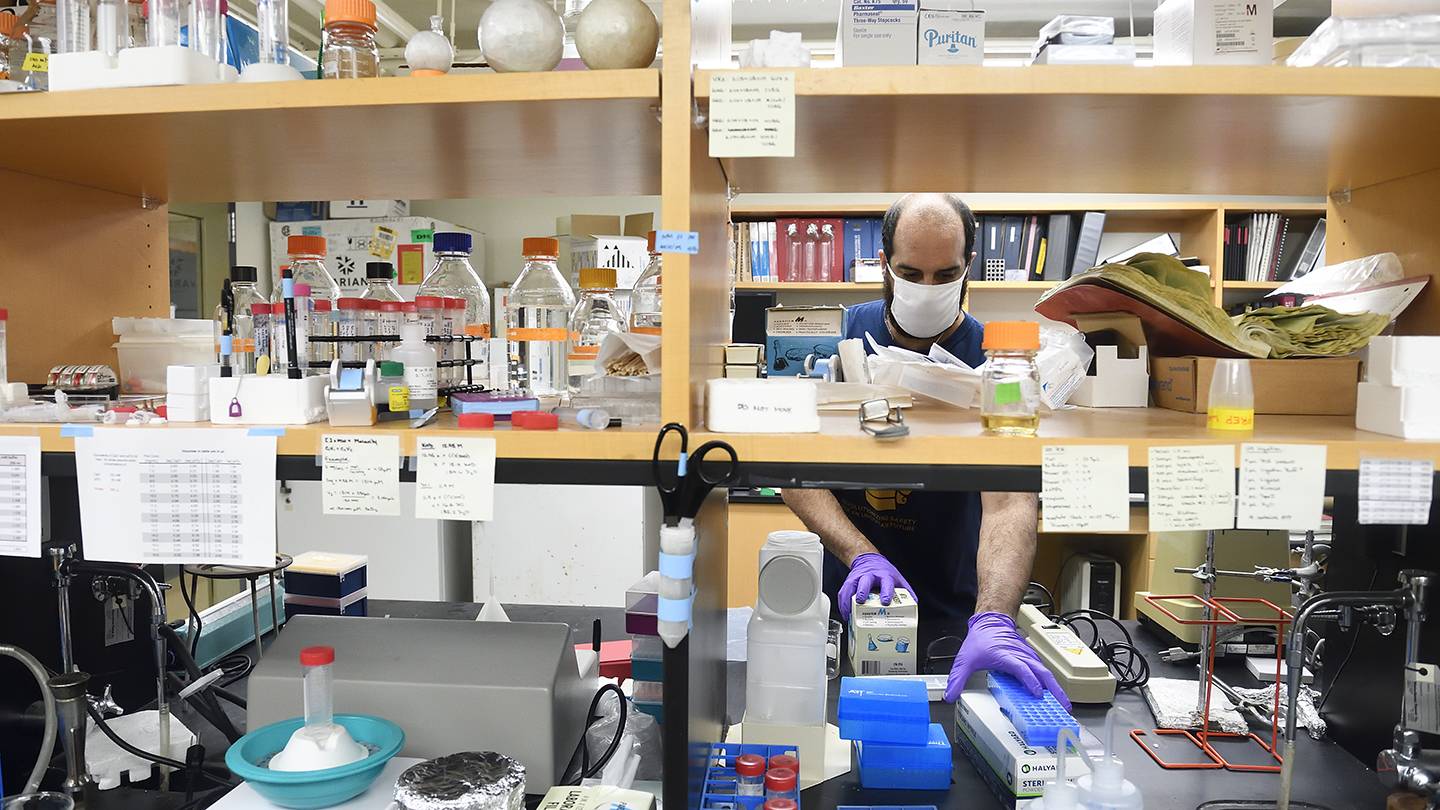

Image caption: Reopening facilities means cleaning surfaces, establishing new lab safety protocols, and inventorying stock. Here, postdoctoral fellow Aaron Robinson of the Department of Biophysics organizes lab equipment and materials.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Chemist Steven Rokita, who studies a group of elements called halogens in his laboratory in Remsen Hall, counts himself lucky that the majority of his group's work was hibernated in a specialized deep freezer, so there wasn't too much material that was lost during the shutdown. But in addition to rethinking the physical space of the lab and how the people inside it interact safely, Rokita is also considering new ways to conduct collaborative research with other laboratories—a hallmark of his interdisciplinary work.

"We are experimental scientists, so there is a limited amount of work that can be done outside the lab, but we also can't do all of our research in just our own labs," Rokita says. "There's a lot of coordination in the department for our core facilities. All of our students are dependent on communal equipment, so that's been a challenge."

He says he's grateful for the collaboration and coordination shown among members of the Department of Chemistry while operations ramp back up. His team of seven grad students is looking forward to making up for lost time. "It was hard, psychologically, for my students," he says. "The shutdown meant their professional advancement was put on hold, and that's always very frustrating."

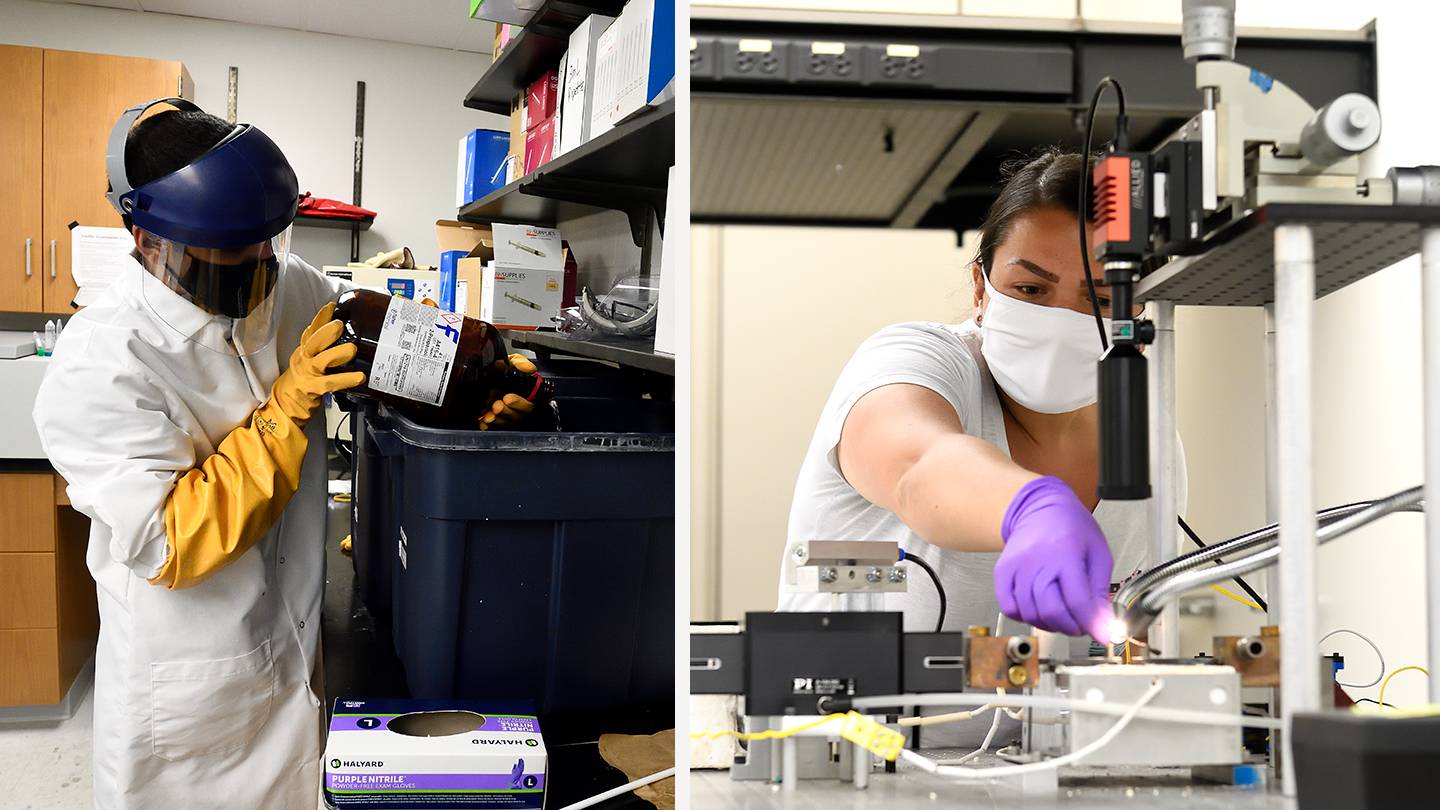

Image caption: Left: Sreyas Chintapalli, a graduate student in Susanna Thon's Electrical and Computer Engineering lab, prepares acid and base baths as the lab reopens after three months. Right: Postdoctoral fellow Gianna Valentino, a member of Kevin Hemker's mechanical engineering lab, sets up experiments as the lab reopens.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

For some students, the reopening of labs comes as an enormous relief—and not just because it provides important professional development. When Mohit Singhala's laboratory reopens in July, he'll be able to reclaim his living space, rather than using it as makeshift laboratory.

"I cannot wait to return to the Robotorium machine shop and the HAMR lab space," says Singhala, a mechanical engineering doctoral student. "I really miss having access to all the machines, tools, and supplies that we take for granted in our everyday research."

Image caption: Mechanical Engineer Louis Whitcomb fills his hydrodynamic test tank in Krieger Hall, where he conducts research on underwater robotics for oceanographic exploration. During the campus shutdown, nearly a foot of water evaporated from the tank.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

His supervisor, Jeremy Brown, had allowed him to take a microscope and 3D printer home. Two weeks later, Youseph Yazdi and Ryan Bell from the Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design called on him to help two New York hospitals find a way to replenish their dialysis fluid. Supplies were running out after COVID-19 patients unexpectedly presented with serious kidney problems, and members of the hospital had reached out to Johns Hopkins for help. With materials purchased on Amazon, Singhala used common household items to develop a small composite adapter that would help hospitals siphon newly developed dialysate solution into the dialysis machines. The manual for constructing and printing the adapter is available free online.

To test for leaks, Singhala used watercolor paints and his microscope, and while waiting for laboratory results of how the device would handle sterilization, he decided to obtain an informal approximation of how two different materials he was considering might behave in the lab's steam autoclave by placing prototypes into a pressure cooker—an appliance his parents had given him nearly four years ago and that he had never used.

"That was the first thing I've cooked in it," Singhala says. "It's now a running joke in my family."

Still others approach reopening with mixed feelings. Graduate student Omkar Bhatavdekar spent part of last week preparing to reopen his laboratory in Croft Hall, where he conducts cancer research for the Johns Hopkins Institute for NanoBioTechnology. Despite being kept from his lab for exactly three months, Bhatavdekar, a PhD student in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, says he has kept busy.

The time he spent under stay-at-home orders helped him think about new creative avenues for his future work while also conducting data analysis and preparing manuscripts for publication. Academic research typically involves such detailed and consuming work that it doesn't often afford the researchers time to take a step back and view their work from a different perspective, he says.

He's also taken the time for personal enrichment. While home, he volunteered remotely with a nongovernmental organization he's worked with for years, Sevali Seva Trust, which provides financial assistance to families in India. He also took advantage of the recently expanded catalog of free Coursera courses offered by Johns Hopkins, completing specialized courses on deep learning, epidemiology, and mathematics. When he did venture from home, Bhatavdekar volunteered with the Johns Hopkins Medicine Incident Command to deliver personal protective equipment to health care workers at Hopkins medical facilities in the Baltimore-Washington area.

After such a fulfilling and restorative break from the lab, it perhaps makes sense that Bhatavdekar views returning to the lab with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. He's also quickly realizing that things won't quite be like they used to be in the labs.

"There's excitement of course, but things aren't hunky-dory like they were before," he says. "We're interacting with our lab mates and in our spaces in a new way. It's maybe not a major challenge, but it's a big part of the experience in the first days of reopening."

Doug Donovan and Will Kirk contributed to this report.

Posted in Science+Technology, University News

Tagged graduate research, research, coronavirus, covid-19