Johns Hopkins men's basketball coach Josh Loeffler felt uneasy. In three days, his team—ranked No. 6 nationally and in the midst of a historic season—would host Penn State Harrisburg in the first round of the NCAA Division III men's basketball tournament.

In another time and place, Loeffler would be in single-minded coach mode, locked in on a game plan for his opponent. But on that Tuesday in early March sitting in his office, Loeffler didn't know what news the next hour would bring. Word had just come that a student at Yeshiva University in New York, one of four schools set to play at Homewood campus that weekend, had tested positive for COVID-19. Loeffler and his players, who dropped by his office or texted him, wondered if their game would be played. Would there even be a tournament? Over the course of the next two days, a Yeshiva professor was diagnosed, and the first COVID-19 cases in Maryland were reported. What should have been a meaningful game of postseason basketball under normal circumstance now, in light of recent events, bordered on meaningless. Players' parents worried about the health risk. The Blue Jays practices suffered noticeably in the days leading up to the game, Loeffler says. They lacked the usual crispness and urgency. Players and coaches were clearly distracted; the news cycle and anxiety impossible to block out.

"I was in meetings constantly about what was going on," Loeffler told me during a Zoom call in May. "We thought we had one answer about playing, and the situation changed. It was the strangest week of my life as a basketball coach. And I'm sure it was a strange week for every one of my players. We just kept seeing the situation evolve and grow, along with our understanding of what was going on in the rest of the country and the virus itself."

Athletics Department staff checked in regularly that week with Jonathan Links, the university's vice provost and chief risk and compliance officer. Links, an expert in crisis management, was part of a core group of university and Johns Hopkins Medicine leaders closely monitoring the emerging outbreak and advising President Ronald J. Daniels and other key decision makers on next steps. What particularly troubled Links, director of the Center for Public Health Preparedness at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, was the thought of more than 1,000 fans packing Goldfarb Gym, given so many unknowns about how the novel coronavirus spreads and how pervasive it was in the U.S.

On that Friday, March 6, the day of the game, Johns Hopkins announced that it would not admit spectators to the tournament games, a shocking and symbolic step amid the evolving outbreak. Loeffler says he learned the news a little before midnight and immediately told his players, who were initially upset, though they understood the reasoning. The decision was based on new guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on large gatherings, including sporting events, which warned they could introduce the virus to new communities. The previous day, Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency in the state. Fans, family members, and friends, some who traveled from several states away to attend the weekend's games at Homewood and were already in Baltimore, were told to stay off campus.

There would be no wall of "Go Hop!" cheers. The home court advantage lost. The Blue Jays opening round game was instead played with just players, coaches, referees, and a handful of Athletics staff in the 1,100-capacity gym. Loeffler described the atmosphere as "eerie," more a closed-door scrimmage, with sneaker-screeching the loudest noise. Johns Hopkins would lose to Penn State Harrisburg in double overtime, but as heartbreaking as the defeat was for the players, the real story was the empty bleachers. The next morning, ESPN's SportsCenter led with the news, reported widely in the media as the first U.S. sports event held without fans because of the new coronavirus. Less than a week later, all major U.S. sports—college and professional—would suspend their seasons.

Given what was known at the time, and even more so in hindsight, Links says, the university made the right decision.

"This was a pure matter of public health," he says. "We asked ourselves: 'What's the right thing to do?' And having a packed gym was not right, and certainly not worth the risk."

What followed was a cascade of monumental steps by the university to slow the spread of COVID-19 and protect not just Johns Hopkins students, faculty, and staff but the public at large. By mid-March, just a week after the fanless basketball game, the university transitioned to remote learning as students were told to return home; nonessential staff were first encouraged to telework, a policy that later became mandatory; and on a massive scale, laboratories and research programs across the university were ordered to suspend their operations. The university didn't grind to a halt, but the brakes were firmly applied.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins needed to lead by example, Links says, even if that meant being more aggressive with social distancing measures than its peers—and more restrictive than what the CDC recommended at the time. The basketball game, he says, probably sent a message.

"We have the No. 1 school of public health, and very early on in this we relied heavily on our own experts and expertise for decision making, and that is what still mostly guides us," says Links, a medical physicist and deputy director of the Office of Critical Event Preparedness and Response. "Obviously, executive orders and directives at the federal and state level are critical, and we would never do anything against those. But in terms of going further than those, that's something we're always open to from a public health perspective. We have our own sense of the health sciences and what the right thing to do is."

In a story I wrote about Links eight years ago, the headline dubbed him Johns Hopkins' unofficial chief worrywart. Speaking to me on Zoom, Links says he still gets called that now and again, and the description is apt. He is paid to worry. For going on two decades, Links has been the instrumental go-to man on emergency and crisis planning. Name the event—H1N1 outbreak, gunman at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, earthquake, 2015 protests—and Links has played a role directly or indirectly in the response, as well as the hindsight thinking that followed. His fingerprints can be found on nearly every crisis-related group, activity, and protocol throughout the institution.

In February, the university administration assembled a multidisciplinary team, including Links, to identify and plan for a range of scenarios and potential near- and long-term impacts of what was then an outbreak and not yet a worldwide pandemic. Even before that, in early January, the university was tracking the spread of the virus and advising the JHU population accordingly, in particular those who had recently traveled to China.

By early March, the university had set up an incident command center in a conference room in Garland Hall, a sort of war room where senior leadership met daily, often several times a day, to discuss action plans and contingencies based on the evolving information. In this room Links and Stephen Gange, executive vice provost for academic affairs and an epidemiologist by training, talked a lot of shop.

"Jon and I had both been closely following what was happening in China, where the virus was clearly getting out of control," says Gange, an international leader on HIV research who, before joining the Provost's Office, was the senior associate dean for academic affairs at the Bloomberg School. "Even before our incident command was set up, we were taking a close look to see what we might be in for. But it wasn't until the second week of March that we started to really ramp up things and prepare for what ultimately happened."

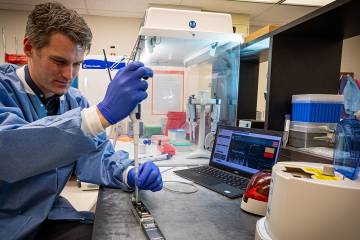

Image caption: Biology lecturer Eric Johnson records a lab experiment for his students after Johns Hopkins switches to remote learning.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Years before, Gange says, the university ran an incident command tabletop scenario, an annual exercise which Links leads, on a pandemic flu outbreak. "Back then, the pandemic flu was something that was of high concern, for exactly the reasons that we're seeing now," Gange says. "I remember writing to Jon as all of this was coming up. I said, 'It looks like time to pull out all of those emails and correspondence communications about pandemic flu.' He said, 'Yep, that's exactly what we're doing.' [That exercise] was helpful because it did set some guidelines and boundaries and ways of evaluating that we could start from. And maybe that did help us be a little bit further ahead of the curve than some of our peers."

In those early days, Gange says, members of the incident command team talked regularly with academic leaders at Johns Hopkins and counterparts at peer institutions. With hundreds of new COVID-19 cases reported daily, as the days went on it wasn't a matter of whether students would be sent home, but when.

"We were seeing the pressure build and what needed to be done early on," Gange says. "Over the course of a few days we made, I think, a series of bold moves, such as deciding to go remote for teaching, closing down research, evacuating the dorms, and sending people home. All of those were decisions our peers ultimately took. We were all trying to filter the information, which was coming at us quick."

The first broad-stroke move came on March 10, when President Daniels announced that Johns Hopkins would transition to remote instruction for both undergraduate and graduate students across all divisions. Effective the next day, in-person classes would be canceled. Students were directed to leave campus by 5 p.m. on March 15 and encouraged not to return to campus following spring break. Living accommodations were put in place to support students who needed to remain on campus, in particular international students.

A series of smaller but still significant steps were also announced. For faculty, graduate students, and staff, all nonessential university international travel was prohibited, and all nonessential university domestic travel strongly discouraged. All tours, admissions events, and alumni events (both on and off campus) were suspended.

Image caption: The Homewood campus has been largely empty since the university made the decision to move to remote learning and pause research not related to the coronavirus.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The decision to close the residence halls was not straightforward, Gange says. Initially, the university encouraged but did not require students to move out. Some wanted to stay, thinking they could still use the library, meet with faculty, and conduct research, even with classes going remote. "I remember being at a meeting where we basically had to say, 'We can't support this,'" says Gange, who has two college-age daughters, one of whom attends Johns Hopkins. "The public health situation was such that we were concerned for the students, and we just couldn't rationalize having a large number of students remain on campus."

Kevin Shollenberger, vice provost for student health and well-being, says that period in March was an extremely anxious time for Hopkins students. The university did its best to keep students informed about the unfolding situation, he says, updating them every step of the way. But as is still the case today, outbreaks make it difficult to plan too far ahead.

"Some of the most common things we heard back then—and since—are just a sense of loss: of their semester, this in-person experience, having daily contact with their friends and faculty," he says. "It's difficult for anyone not knowing what's going to happen next, or how to plan."

Shollenberger realized things were about to drastically change during a February visit to the Carey Business School, which has a sizable Chinese student population. "When the travel ban from China started happening, I realized, 'Wow, this is going to totally alter how we do business as a global institution,'" he says. "For me, that's when it really started to hit home that we had to think differently about how we were going to operate from here on in."

By March 18, with students now mostly off campus and nonessential staff working remotely, the last sizable population left on campus was researchers. Denis Wirtz, the school's vice provost for research and a professor in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, knew that couldn't continue.

Wirtz says he and colleagues spent days agonizing over what they knew had to be done: wind down research operations at Johns Hopkins—no small matter for the nation's leader in federal research and development funding. At the time, researchers at the university's nine academic divisions were conducting thousands of projects in more than 150 countries. How do you pull the plug on the lifeblood of the university? When public health experts tell you that's what needs to be done, Wirtz says, you just do it.

"We decided to suspend research operations at a time when nobody had taken any bold action in terms of closing labs or preventing faculty and student fellows from coming on campus," says Wirtz, himself a cancer researcher. "We had already taken the action that undergrads should be leaving the campus and not come back, so why on earth would we then keep our graduate students and postdocs on campus? And so we said, at a minimum for consistency—but more importantly to actually take social distancing very seriously across the board—it was time to take an action that was against our best instincts."

Only essential personnel could remain on campus, those required to ensure that experiments that had been running for weeks, months, and even years could be safely completed. And then those people had to go, too. The message to suspend operations went out on a Sunday; researchers had until Wednesday to stop ongoing experiments and leave the lab.

"Think of it this way—in the course of days, we went from 100% full research activity down to something in the area of 5%," Wirtz says. "It's really one-off people coming in to reboot a computer, to add liquid nitrogen to a fridge, and that's it. Basically, all non-COVID-19 research is entirely stopped."

Soon after, Harvard, Stanford, Duke, MIT, and other major research institutions would follow suit. Wirtz says he thinks JHU's peers were paying attention. "When the university with the premier school of public health is telling itself it's time to stop people from being next to each other in labs, maybe it was time for them to do the same."

By and large, Wirtz says, researchers understood. "They live and breathe their research every day, but a lot of the feedback we heard was positive. They knew this was a tough decision to make, but it was the right decision," he says. "In my own lab we had to throw away a lot of cell cultures and work that was ongoing, some of which involved very precious cells. But we had to stop. We asked ourselves, Is this really an essential experiment at this moment in time?"

Some work was not only essential but needed. At the same time some projects were mothballed, Johns Hopkins launched a massive and ambitious initiative to repurpose research facilities and allocate new financial resources to projects that advance our understanding of COVID-19, prevent its spread, and care for the sick. As of press time, $6 million in university funding had been redirected to support roughly 260 scientists and researchers working on 25 projects including treatments, detection tools, and vaccine developments.

When I initially spoke with Links, he asked me not to make this story just about him.

"This is really about a lot of people who have never been working harder in their lives," Links says. "I happen to be coordinating a lot of the pieces, but this is an all-hands-on-deck moment in terms of the entire university leadership team."

Links says none of the steps was taken lightly, knowing that sending staff, faculty, and students home would be massively disruptive to the operations of the university and the vital work being conducted on all campuses.

"We obviously deeply care about and are committed to the mission of the university and to all our people. And so, trying to continue to accomplish our mission while keeping people safe and healthy is a balancing act," he says. "There was no decision that was a, quote, no-brainer. And the people dimension is first and foremost. That's probably the No. 1 message I want to get across here. The people dimension has been the primary focus every time, and will continue to be as we see our way through this period in our history."

Posted in University News

Tagged university news, coronavirus, covid-19