When artist Nicoletta Daríta de la Brown came across postcards with photographs of unidentified Black women from the early 20th century, she felt an immediate kinship. "I saw them and wanted to know more," she says of the images she unearthed from the archives of the Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries. "What were their lives like? What were their struggles? How could I, as a Black woman from Baltimore, engage with them and bring their stories back to life, even in an intangible way?"

Realizing she couldn't leave the women nameless and alone in the archives, de la Brown made the postcards an integral part of her art installation, Be(longing), on view recently at George Peabody Library in Mount Vernon—and created as part of her work as one of the university's first fellows in the public humanities. Embraced by colleges, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations across the United States, Canada, and other parts of the world, the public humanities is an emerging field in which practitioners form partnerships and work collaboratively with community members to generate knowledge, preserve cultural heritage, and raise awareness about (or even help solve) social justice problems.

Yet its rise comes at a time when the number of undergraduates majoring in the humanities is dwindling. In 2020, for instance, less than 10% of undergraduates across the country majored in English, communications, history, philosophy, or foreign languages and literature, compared to 35% in 2012, according to the Hechinger Report. Remove the popular undergraduate major "communications" from the equation, and the number drops to a mere 4%. At Johns Hopkins University, none of the 10 most popular majors fall within the realm of the humanities, and only about 1% of students major in English, history, art history, or philosophy.

Why the decline? Studies attribute it to a mix of factors: rising college tuition, the Great Recession of 2008, and the higher earning potential of a degree in science, technology, engineering, or math (STEM)—to name a few. But proponents of the humanities consider subjects like philosophy and history valuable in and of themselves, regardless of a graduate's earning potential. And they're looking for ways to make their fields more relevant and applicable.

Enter the public humanities.

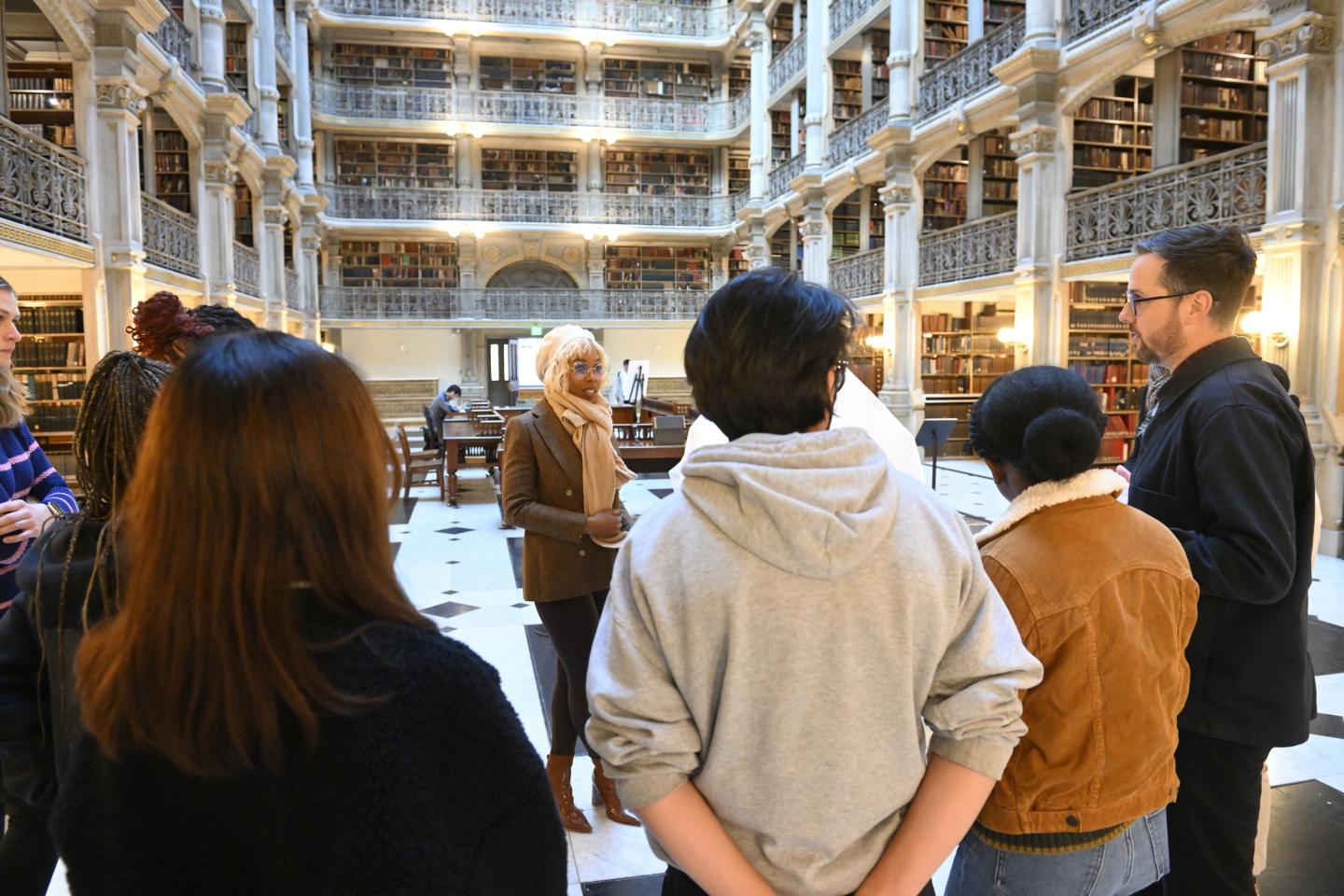

Image caption: Nicoletta Daríta de la Brown speaks with Joseph Plaster’s Public Humanities & Social Justice course

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

As a public humanities fellow for the Winston Tabb Special Collections Research Center at the Sheridan Libraries, de la Brown is spending two years researching and utilizing materials from the university's rare book, manuscript, and archival collections to create art that engages the public and enhances understanding both within and outside of the university. Joseph Plaster, who launched the fellowship program through his role as director of the Tabb Center and curator in public humanities at the Sheridan Libraries, believes partnerships with public humanists like de la Brown are key to breaking down barriers between the local community and academia.

"Through the Tabb Center's public humanities fellowship program, Johns Hopkins is building bridges with community organizers, artists, cultural workers, public historians, and other kinds of knowledge-creators outside of academia," Plaster explains. "These collaborations enable humanists across Baltimore to assert the public value of the humanities, develop new ways of telling our histories, and imagine more just and livable futures."

Also see

While he runs the fellowship program, Plaster is a public humanities scholar and practitioner in his own right, with a doctorate in American Studies from Yale University and a book released earlier this year, Kids on the Street: Queer Kinship and Religion in San Francisco's Tenderloin (Duke University Press), about the informal support networks that enabled abandoned and runaway "street kids" to survive in San Francisco's downtown Tenderloin neighborhood. The book evolved out of his experience as a public historian at a small nonprofit organization, the GLBT Historical Society, in San Francisco. There, "I recorded the oral histories of individuals living in a working-class, queer neighborhood in the process of gentrifying," he says. "I then used what we compiled to create exhibitions, radio documentaries, mediated discussions, and listening parties—all of which shaped contemporary debates about gentrification, displacement, and the policing of homelessness.

"I realized around that time," Plaster continues, "the potential of the humanities to address pressing political questions and social problems, and to bring people together in ways that bridge cultural divides."

Since coming to Johns Hopkins in 2018, Plaster has turned his attention to Baltimore and launched programs that position artists, performers, curators, historians, and activists as partners in research and advocacy. His Peabody Ballroom Experience, winner of the National Council on Public History's 2023 Outstanding Project Award, is "an ongoing collaboration between Johns Hopkins University and the queer and trans people of color who animate the local ballroom scene, whose origins trace back to a performance-based subculture in Harlem in the 1970s," he says. Plaster also sponsors a community-based oral history project, "Vintage T," that documents transgender histories in Baltimore—and teaches classes for the Program in Museums and Society at the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

One of the courses Plaster teaches, Public Humanities and Social Justice, introduces students to the histories of marginalized and indigenous communities in Baltimore, while cultivating skills in research methods like participatory archiving, through which historians and archivists work with the public to document local histories. This semester, his class met regularly with artists, public historians, activists, and scholars from Baltimore—including de la Brown, who spoke with students at the Peabody Library about her latest creation, Be(longing).

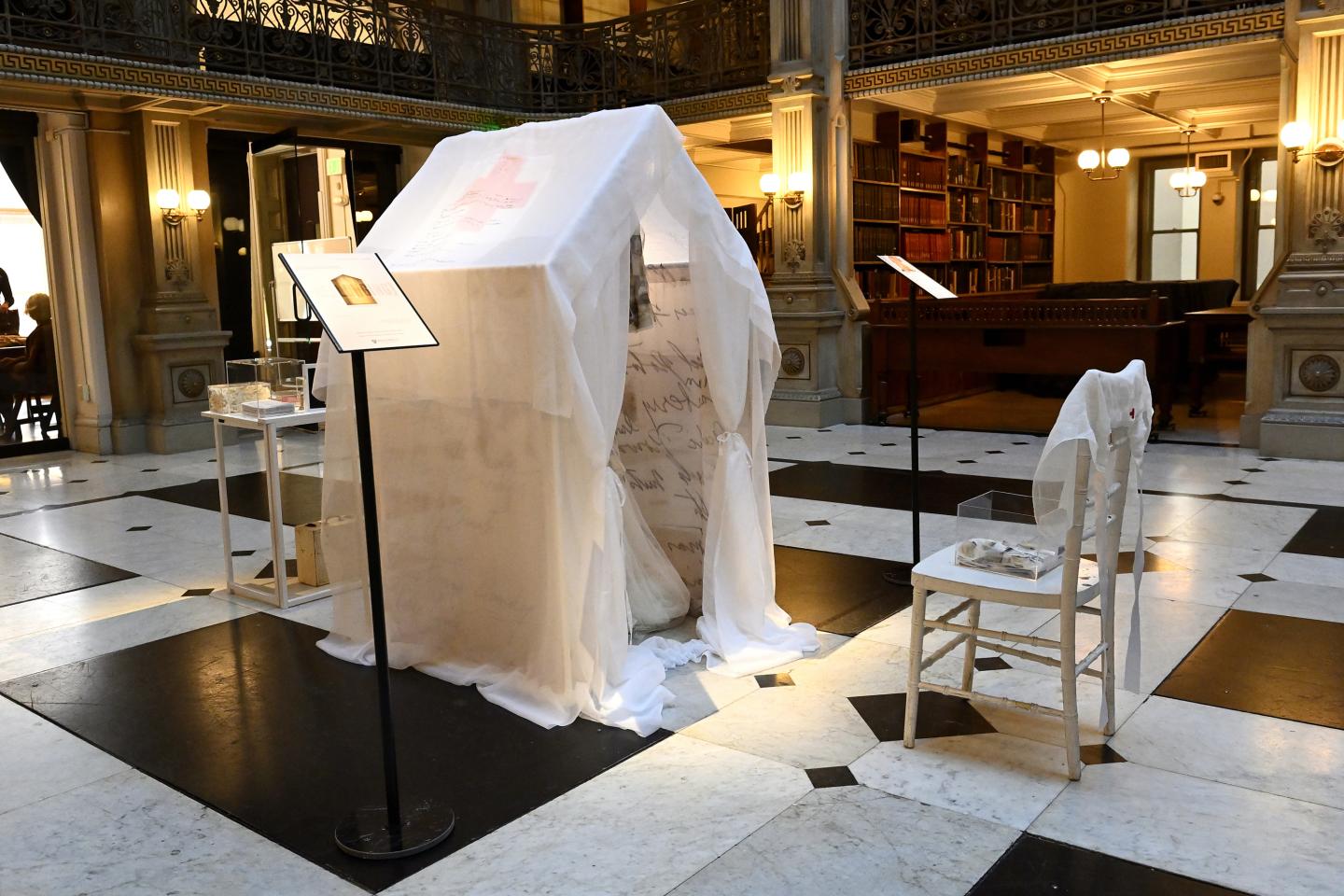

Image caption: Nicoletta Daríta de la Brown’s Be(longing) installation at the George Peabody Library

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Positioned at the far end of the library's ornate stack room, Be(longing) features a small, house-like structure made of white chiffon. A red cross emblazoned on the exterior makes the structure look like a military field hospital, but no soldiers lie on gurneys inside. Instead, a long, white chiffon dress—vacant and uninhabited—hangs in the center. Black-and-white images of the unidentified women from the archival postcards, superimposed on single pieces of fabric and hand-sewn by the artist, adorn the flowing skirt of the dress.

Outside the structure, the stack of century-old postcards lies face-down in a glass case on a make-shift altar. No messages, addresses, or postage stamps appear on the postcards—they are unused and blank, adding to the mystery of the women whose images they bear. Also on the altar are framed photographs of three young girls—black-and-white archival images of jazz greats Ethel Ennis and Billie Holiday, paired with an in-color image of de la Brown, in 1985, at age 4. "All three of us grew up in Baltimore, and I spent time in the archives imagining what it would have been like if we had played together as kids or known each other as adults," de la Brown told Plaster's class. "I had a bow in my hair, and Billie had a flower."

Holiday, like de la Brown, made grocery lists and cooked meals for family and friends. One of her grocery lists resides in the archives, and the artist inscribed parts of it—"potatoes" and "Christmas candies," scrawled in Holiday's slanted cursive handwriting—on the house-like structure's exterior. Also included are notations in numerology from the journal of Ennis, who used the ancient mystical science to calculate life path numbers of loved ones.

"These archival materials, left alone, are full of gaps in history," de la Brown said. "Part of what I'm doing is filling in some of the gaps by putting life back in and making the past relevant to our lives today.

"The [make-shift] altar—and altars in general—are ways to stay connected to ancestors," de la Brown explained to the class. Quoting lines from bell hooks' 1995 book, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, which Plaster assigned as a class reading to contextualize de la Brown's work, he added: "In many Black homes, photographs—especially snapshots—were … central to the creation of 'altars.' These commemorative places paid homage to absent loved ones … so that a relationship with the dead could be continued."

Earlier in the semester, Plaster took his class to meet the legendary New York-based artist Fred Wilson at the Baltimore Museum of Art. Plaster had previously introduced his students to Wilson's groundbreaking exhibit from 1992, Mining the Museum, at the Maryland Historical Society (now the Maryland Center for History and Culture). Here, Wilson juxtaposed and reoriented objects from the museum's collections and storage rooms in ways that forced viewers to confront the harsh realities and ironies of institutional racism. In one part of his exhibit, for example, he displayed a deluxe set of silver repoussé cups and ewers alongside a rusted pair of iron slave shackles. In others, opulent Victorian chairs encircled a tattered whipping post, and fugitive slave reward posters hung behind a nine-foot-long antique gun.

"Fred Wilson inspired countless curators—and museums and cultural institutions—to rethink the narratives they produce for the public," Plaster says. "He was raising questions decades ago about the ethical responsibility of institutions to communities beyond the academy, especially communities of color, long before others were asking these questions.

"Now, partly as a result of his work, institutions are reorienting their mission by addressing matters of social justice and responding to the demands of marginalized communities."

In addition to meetings with Wilson and de la Brown, Plaster's class included a session co-taught by Jessica Shiller, an associate professor of education at Towson University, who spoke to the class about the participatory action research project she conducted about the controversial closing, from 2012 to 2014, of 26 public schools across predominantly Black and Brown low-income neighborhoods in Baltimore City. Described in her 2017 paper for The Urban Review, Shiller's project weaves in the voices not only of school administrators and board members but also students, parents, teachers, and community members, ultimately finding that the school district "acted as a colonial power, at once erasing indigenous culture and reifying white supremacy."

Other guest speakers included Plaster's Baltimore-based collaborators working on the "Vintage T" oral history project and ballroom artists involved with the Peabody Ballroom Experience. "These community-engaged research projects [are helping to] reimagine knowledge production in critical dialogue with institutional norms by prioritizing narrative- and performance-based methods, [which are often] rooted in minoritized publics," Plaster says.

Sonia Eaddy, a community activist who fought to save the historic Black neighborhood of Poppleton in West Baltimore from demolition through eminent domain, also spoke to the class, along with Nicole King, an associate professor in American studies at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. King and Eaddy shared their experience collaborating on a public humanities project, "A Place Called Poppleton," that presents stories from past and current residents of Poppleton. Their public humanities interventions, including the production of historical "zines," enabled Eaddy to successfully save her home from demolition.

For the capstone project of the Public Humanities and Social Justice course, Plaster's students took what they learned and, using Johns Hopkins' archival collections, created their own proposals for public humanities projects. Students focused on Baltimore-based archives, including the Housing Our Story and Baltimore Civil Rights History Project collections.

"Archives have so much potential locked inside of them and so many stories to tell," says Elisabeth M. Long, dean of the Sheridan Libraries and University Museums. "It is exciting to see this public humanities initiative activating archival materials in new ways and engaging a broader range of audiences. I hope it inspires people to see that archives are for everybody."

Giving students advice on their projects, de la Brown encouraged them to think outside the box about the archives. "Any small scrap of paper, a piece of fabric, an old photograph, your Instagram account—these are all archival materials," she told the class. "Don't rush your reaction to something archived. Sit with what you find, and let your ideas and feelings simmer."

Although Plaster knows the projects will likely never come to fruition, he hopes to have instilled in his students the importance of listening and collaborating in the research process. He also hopes students will carry with them a sense of how powerful the humanities can be when put into action.

"Classes like this are part of the most recent 'public turn' in the academy and the desire to create knowledge through participatory action research and collaborative, community-based learning," Plaster says. "They're also part of the shift in academic research from knowing about to knowing with, as marginalized communities around elite institutions become partners in research and not simply objects of study."

Critical to doing this kind of work, Plaster says, is recognizing that knowledge comes in many different forms. "By bringing together the vast knowledge created by the academy with that of artistic and activist communities, and encouraging those groups and ideas to cross-pollinate, new forms of knowledge and politics can emerge."

For the university at large, Plaster and other public humanists are adding new dimensions to humanities scholarship, teaching, and learning, while building bridges to the local community and greater world.

"We remain as fully committed to the study of the humanities as we have ever been, and for good reason," says Christopher S. Celenza, dean of the Krieger School and a history and classics professor at Johns Hopkins. "Our humanities majors consistently go on to grapple with some of the most challenging and complex issues facing our communities, nation, and the world, applying their skills in research, analysis, and synthesis in highly innovative and generative ways. Now more than ever, our future demands the insights that fields like philosophy, history, and literature make possible."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged peabody library, sheridan libraries, program in museums and society