- Name

- Johns Hopkins Media Relations

- jhunews@jhu.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-9009

Not again.

It's the crushing thought so many of us had in the days following the latest, horrifying mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas, where 19 children and two teachers were gunned down in an elementary school—just 10 days after another gunman killed 10 people in a grocery store in Buffalo, New York. In both cases, the shooters were 18-year-old men.

Why does this keep happening and what can we do to make sure it never happens again? The Hub reached out to experts from across Johns Hopkins University for their thoughts on those questions and on how the U.S. can address what seems to be a uniquely American problem.

Make it harder to turn violent thoughts into violence

Paul Nestadt, assistant professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a core faculty member at the Center for Gun Violence Solutions

It is becoming far too common for us to use "far too common" to describe these shootings. Tuesday's gun violence in Texas was a redundant reminder of our continued failure to pass meaningful firearm law reform. Research from our Center for Gun Violence Solutions has demonstrated that permits to purchase, child access protection laws, and extreme risk protection orders all reduce the likelihood of firearm deaths. Lessening casual access to dangerous firearms has been repeatedly shown to decrease rates of suicide and homicide, of which this incident was arguably both.

There is much we can do to address the contributors to violent thoughts, including addressing poverty, broadening access to mental health care, and strengthening supportive networks. But violent thoughts are not unique to America. America suffers more shootings because it is so much easier for even fleeting violent thoughts here to be immediately translated into deadly action thanks to easy access to military grade weaponry. That is a problem we must demand that our legislators address.

More police in schools doesn't solve the problem of easy access to guns

Odis Johnson, executive director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Safe and Healthy Schools, is a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of social policy and STEM equity. He is a leading researcher of social inequity in America.

School safety policy has not slowed the occurrence of school shootings in the United States. Policymakers have allocated more tax dollars to hire more school police after each school shooting. Yet the National Center for Education Statistics reports the number of school shootings with injuries or fatalities has increased steadily for the last seven years. Law enforcement on school grounds is not an effective policy response to the kind of tragedy that occurred in Uvalde, Texas.

Instead of addressing the problem of easy access to guns, lawmakers have increased the placement of law enforcement within our schools. This has led to higher rates of school arrest for minor school disturbances and made many of our young people feel like suspects instead of students. Our research shows students who attend schools that rely on law enforcement and other means of surveillance have lowered test score performances and rates of college attendance relative to students in other schools with similar social background characteristics. Knee-jerk school police policies have not ended school shootings, and may have undermined achievement in U.S. schools.

While NCES data show a 10-year decline in reports of students with weapons at school, rates of gun-related injury and death have increased over the last seven years and are currently higher than they have ever been recorded.

Gun access remains high in the general public. The high number of guns in the U.S. increases the likelihood that young people will access them illegally. Schools and their students are not isolated from the impact and problems associated with the abundance of guns in their homes and communities. Making schools safer requires policymakers to address how young people access firearms. This can be achieved with biometric fingerprint locks for firearms and other gun permit requirements.

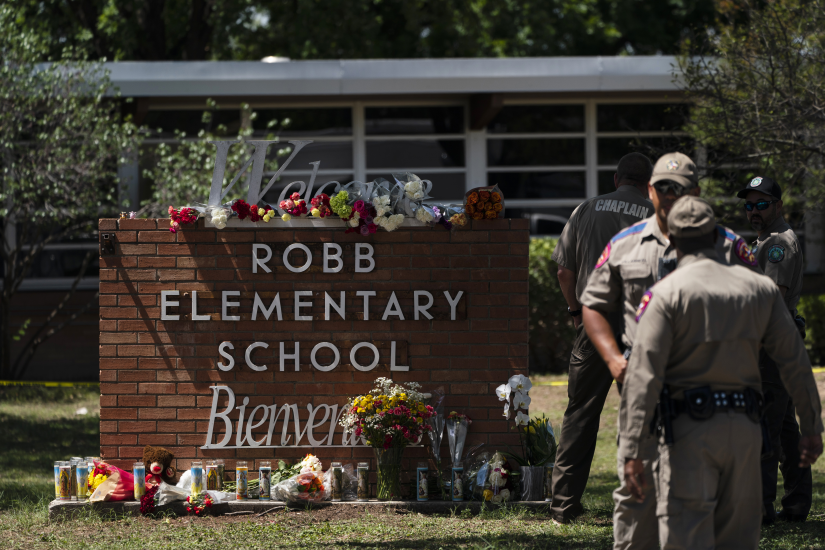

Image caption: Flowers and candles are placed outside Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, Wednesday, May 25, 2022

Image credit: AP Photo/Jae C. Hong

Focus on humiliation in schools as a driver of withdrawal, confrontation, and violence

Sheldon Greenberg, a retired professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Education with a joint appointment in the School of Public Health. Greenberg is a former police officer and former Associate Director of the Police Executive Research Forum. He continues his research on humiliation in schools, selection of school resource officers, and characteristics of safe and healthy schools.

Humiliation is a form of emotional abuse that affects people of all ages and walks of life. For many people, especially young people, people of color, and those in marginalized groups and communities, humiliation is directly connected to being judged and/or treated as different. Students with special needs are particularly vulnerable. Research on humiliation in schools and approaches for reducing it is lacking.

Humiliation is a factor in bullying, cyberbullying, fear, violence, hate, discrimination, vengeance, self-harm—and it is a factor that contributes to many school shootings. Humiliation is recognized globally as a barrier to social inclusion; yet it has received limited attention in research, policy, and teacher and administrator education and training.

Also see

All students have a fundamental right to participate in their school and community free from degradation. Most students look to school as a place of acceptance, impartial treatment, and protection from harm. Some students experience humiliation at school at the hands of peers, teachers, administrators, and parents, and its effects linger. Of course, not all students who are humiliated commit acts of violence. For all students who are humiliated, it is hard to forgive or forget the person who demeaned them, especially if the act occurred in the presence of others.

Humiliating behavior is learned and can be changed through a collective effort by school stakeholders. Understanding the practices used by people to humiliate is a first step toward preventing the abusive behavior. It is important to avoid masking humiliation under the catch-all term "bullying." Strategies and approaches to reduce humiliation in schools include assessing the culture, adopting a human rights doctrine, and establishing policy and training for teachers and staff. It requires understanding the difference between humiliation and "simple teasing," establishing support systems for students who have been humiliated, addressing those who humiliate, and more.

Ensure school buildings are secure

Annette Anderson, deputy director of Johns Hopkins Center for Safe and Healthy Schools

When I heard about the tragic shooting in Uvalde, Texas, my first thought was: How did a gunman get into the school? Among the many policy issues the Uvalde shooting raises, for those who work in schools, one of those is building security. From experience I know that school administrators are frequently conducting building sweeps in preventative action mode, searching out the gaps where something could be wrong or missing or broken, instinctively checking locks and peering around corners and into dark spaces on building walks early in the morning looking for things that could potentially be problematic for a child or staff member, and staying on high alert for the areas in their buildings where possible trouble could be brewing. And yet I suddenly also remembered all of the days as a principal when the doors between the lunchroom and the recess yard of my school were opened—from the beginning of the first period lunch to the end of the third lunch shift—and I realized that perhaps it would not be too far-fetched for a former student to recall where the doors would be opened in school at that time of day. Clearly, one conversation to emerge from this tragic period is to consider how we can make small yet consequential building upgrades to school doors so that every child can be safe and healthy in school. It's also true that a school community can do everything right and have a robust security plan in place and still fall victim to tragedy.

Leaders who fail to act are culpable

Spencer Cantrell, federal affairs adviser at the Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Cantrell uses her experience representing survivors to promote evidence-based and equitable legal reforms at the federal level to reduce violence.

I am heartbroken by the shooting that occurred in Uvalde. As a parent, the news hits closer to home, and I cannot imagine the anguish of the families who lost their loved ones. As a professional working on federal policy to prevent gun violence, I am frustrated by the inaction. Leaders who fail to act are also culpable in these situations. I hope that we can use Extreme Risk Protective Orders at the state and federal levels to prevent firearms from ending up in the hands of those who pose a risk to themselves and others.

There are policies that work to prevent gun violence—if we deploy them

Lisa Geller, state affairs advisor for the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions

The news of yet another mass shooting leaves me angry and frustrated. The community in Uvalde, Texas, now joins the long list that no community wants to join. What frustrates me most is that we have solutions to our gun violence epidemic. We know which policies—including firearm purchaser licensing, extreme risk protection orders, and firearm removal for individuals with histories of domestic violence—work to reduce and prevent gun violence. Research I published last year found that nearly 70% of mass shootings in the U.S. have a connection to domestic violence. In the case of the mass shooting in Uvalde, we know that the perpetrator shot his grandmother before arriving at Robb Elementary. Identifying those at the highest risk of violence—including those with histories of domestic violence—and ensuring that they cannot access firearms is critical to preventing gun violence.

We cannot sit around and wait for the next shooting to occur. Public health means prevention, and our center will continue to educate policymakers and the public about preventive measures to curb this epidemic.

Turn heartache into action

Katherine Hoops, assistant professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine and a core faculty member at the Center for Gun Violence Solutions

As a pediatric intensivist physician, I care for the sickest children—those who are critically ill and injured requiring life-saving therapies in the face of devastating disease. My heart aches any time I lose a patient, when everything medicine has to offer isn't enough.

But as a violence prevention researcher, when I lose a patient to gun violence, there is a special heartache that is mixed with rage because I know there is so much that medicine and public health have to offer that wasn't done to prevent the loss of that precious life.

As a mother, I am heartbroken for the families whose children did not come home from school at Robb Elementary, for those families and a community whose lives are forever changed. I am also fueled by a righteous anger and determined that this can truly be the last time. I send my thoughts and my constant prayers, and I also roll up my sleeves to work for prevention.

We can prevent violence. Through comprehensive firearm licensing policies, large capacity magazine limits, safe firearm storage, and extreme risk protective orders but also hospital-based and community-based violence intervention programs, police reform, addressing social determinants of health, and dismantling structural racism. But to do this, we must all turn our heartache into action.