When the COVID-19 pandemic made its way to the United States, Johns Hopkins alum Stephen Farias began thinking of ways to help. As director of engineering at DiPole Materials, an electrospinning company in the Baltimore neighborhood of Pigtown, his mind immediately jumped to the company's Elmarco machine, which creates electrospun nanofibers for commercial prototyping or small-scale production. The machine, he realized, is also capable of manufacturing nanofibers with filtering capabilities similar to those of an N95 mask.

DiPole's representatives pitched the project to investors and quickly received the funding they needed. The last piece of the puzzle was who would do the actual labor. In order to make as many filters as possible, the Elmarco machine needed to run 24 hours a day, which would overburden DiPole's full-time staff.

DiPole put out a call to students from local colleges, asking if anyone with experience handling chemicals would like to help. The group received an overwhelming response, particularly from Johns Hopkins students. In total, 13 current students and graduates from the Whiting School of Engineering and Krieger School of Arts and Sciences are now working on the project.

"I was actually looking for community organizations and volunteer groups to join to help in the fight against COVID-19 when I got the message about working at DiPole to help produce filter material," says Drew Grant, a PhD candidate in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Whiting School. "I was happy to contribute in any way I could, and to help with filter production by gaining wet lab experience at a local startup was serendipity."

Though the project features students from a number of local colleges, the sizable contributions from Johns Hopkins students is just the latest in a rich history of collaboration between the university and the company. James West, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, helped co-found DiPole in 2015, and the company's first piece of technology originated in his lab. Farias is also not the only Johns Hopkins graduate on DiPole's staff, as the company has hired multiple Hopkins alumni in recent years.

Image caption: Drew Grant works with the Elmarco machine

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The majority of the Hopkins students are performing quality control for the project, ensuring that the material being produced by the Elmarco machine meets filtering specifications. This involves operating the machine to produce material and preparing the solution for the next shift. Each shift is eight hours long, and student pairs work two to three times a week at DiPole's production site. The same students work together for each shift, ensuring that if someone does contract COVID-19, it will not spread to all the project's workers.

"We make enough material for about 2,000 mask filters per day," Farias says. "Once the filters are created, we send fabric rolls of our materials to other manufacturers that put it into the final mask products. We are distributing to several local mask fabrication companies, as well as some large local and domestic textile manufacturers."

Beyond performing the invaluable task of creating the actual filters and making sure they're up to safety standards, graduate students contribute superb problem-solving skills to their tasks, according to Farias. For instance, Adebayo Eisape, a PhD candidate in electrical and computer engineering, has become the project's on-call hardware technician, ready at any time, day or night, to step in to make fixes to the constantly running Elmarco machine.

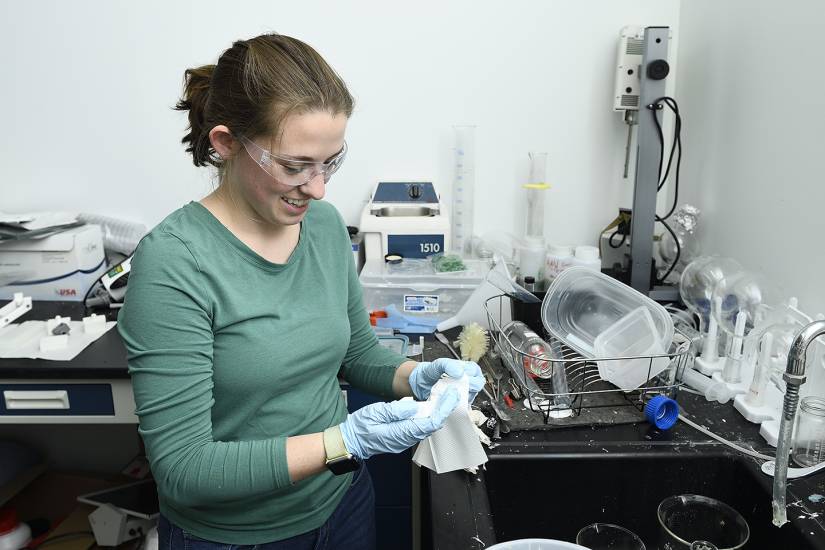

Image caption: Valerie Rennoll

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

"Right now, the machine is working more in one day than it usually does in a week, which is like having a car drive 50,000 miles in a month," Farias says. "I knew Bayo is a whiz with hardware, electronics, and getting things to work, so I gave him the manual of all the different components of the machine to study and be ready if anything breaks down. It's a crucial role because if the machine does break down for a significant amount of time, it'll halt our production of the filters, which we can't afford to have happen."

For all the participating students, the project has been an opportunity to help in the fight against COVID-19, while leaning on skills and values that they have learned from their time at Johns Hopkins.

"While at Hopkins, I've been trained to collaborate with others, think critically, and troubleshoot," says ECE doctoral candidate Valerie Rennoll. "This allowed me to integrate with the project at DiPole quickly and help contribute. I've really enjoyed working on the project so far. Not only do I get to contribute to the fight against COVID-19, but I also have the opportunity to learn a new piece of equipment and look at the manufacturing side of nanofibers. It's also an added bonus that I get to leave the house a few days a week to help."

Joining Farias, Eisape, Grant, and Rennoll in the Whiting School contingent is a sizable group from the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, including alum Matthew Davenport, PhD candidate Jacob Mehlhoff, and undergraduate students Kristen Nixon, Kristen Petersen, and Alison Shapiro, as well as alum James Shamul, from Engineering Management. The Krieger School of Arts and Sciences contingent is composed of PhD students Eric Marro, Calvin Hong, and Ryan Weeks from the Department of Chemistry.

Posted in University News, Student Life, Alumni

Tagged alumni, electrical and computer engineering, coronavirus, covid-19