The 19th Amendment barring states from denying voting rights based on sex was passed a century ago, but the movement failed to address the broad disenfranchisement of huge swaths of Americans—most notably black Americans. As Johns Hopkins celebrates this important milestone in American democracy with a yearlong commemoration, it is also examining the movement's shortcomings and enduring legacy.

Image caption: Martha S. Jones

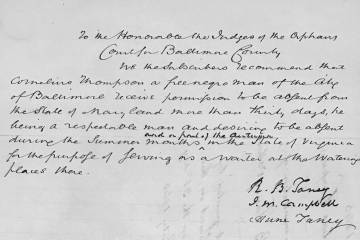

Martha S. Jones, a professor of history at Johns Hopkins, has written extensively about how black Americans have shaped the story of American democracy, including voting rights. Jones spoke recently about the 19th Amendment, its larger context 100 years ago, and what its history can teach us about voting rights today.

Why is it important to recognize the centennial of women's voting rights?

It's important to remember this chapter in the struggle for voting rights because we live in a time where voting rights are being whittled away, attacked, and undermined. It's hard to dive into voting rights questions in the 21st century without appreciating where they've come from. Among the long stories of our country is one in which voting rights have always been a battleground; they have always been buffeted about by politics, political whim, and factions—along with racism, xenophobia, and sexism.

The most important reason to remember the struggle around the 19th Amendment is that it then lets us ask better questions about voting rights today.

What might one of those questions be?

I'm very interested in the career and work of Stacey Abrams from Georgia. Some readers will be familiar with her run for the governorship and then, at the end of that campaign, her recommitment to registering voters in Georgia and getting out the vote in Georgia and, by implication, nationally.

To me, it would be a mistake to understand Abrams as somehow a creature of the 21st century alone, or someone who comes of age post-Obama, or comes into the political fore after the undermining of the Voting Rights Act. I see Abrams as working in a much older, two-century-long tradition of African American women who have sometimes been inside, and sometimes been outside, conventional halls of power. Black women have developed their political analysis at the intersection of women's rights and African American rights, and have always known that the 15th Amendment [which barred states from using race when deciding who could vote] and the 19th Amendment were not resolutions to the problem of voting rights; they just changed the terms by which African American women, in particular, engaged in the struggle for voting rights.

Stacey Abrams is telling us something about our own time, but she also allows us to understand how we got here and how deeply entrenched voter suppression is in our history. Her work helps us appreciate, then, how difficult it is to set that tradition to the margins or eradicate it. Most of U.S. history is a history of voter suppression rather than voting rights.

Who are some of the lesser known figures behind the 19th Amendment, and what do they have to teach us?

Many Americans don't know that the very first woman to speak in public about politics to a mixed audience was an African American woman in Boston in 1832 named Maria Stewart. Stewart had a short career as a public speaker in a city where radical abolitionism was on fire, where there was a thriving African American public culture. Stewart entered politics out of a set of principles that then informed African American women's work around voting rights for a very long time.

First and foremost, she wanted black women to examine the political landscape and analyze it with a sophisticated lens that came out of their own experience. She lamented and then decried how not only the insights but also the talents that she and women like her possessed were squandered and suppressed at a moment when black Bostonians, and African Americans generally, strained to sustain themselves and to create themselves as a force in the nation's politics. They were concerned about anti-slavery, they were concerned about civil rights, and Stewart says in essence, "So am I, and why is it that you're keeping me out?"

She's not someone who talks about voting. The story of women and the vote does not begin with women demanding the ballot. Instead, it began with a set of experiences, challenges, and questions about old limits on women, and with new urgencies that women felt. Even before white American women joined the antislavery movement—and discovered through antislavery activism their political identities—someone like Stewart was at the cutting edge.

It's not the kind of story we expect because we frequently hear that the story of women and the vote began at Seneca Falls in a women's convention. Maria Stewart is a reminder that African American women were never, in significant numbers, part of those organizations that we associate with women's suffrage historically. In 2020, we have a chance to understand how American women came to politics and power. To do that, we must ask where black women were, what they were doing, and what they were saying. Stewart reminds us that not all women came to political power by way of a women's suffrage movement.

You mentioned the 15th Amendment that barred states from using race in deciding who could vote. What is its relationship to the 19th Amendment?

In the years leading up to the 19th Amendment, there's a terribly fraught bargain that circulates in Congress: "Let's repeal the 15th Amendment in exchange for passing the 19th Amendment." It was a bargain that would have permitted states to bar voters based upon their race while prohibiting them from barring votes based upon sex. The bargain hoped to keep all black men and women from the polls, while opening them to white women.

That bargain fails, but remembering that when African American suffragist and club movement leader Mary Church Terrell was calling for women's suffrage, she also had to navigate a complex set of challenges. She did not find a partner in her push for black women's votes from white women suffrage leaders such as Carrie Chapman Catt and Alice Paul.

This was a lost opportunity, in my view. American women might have linked arms across the color line and changed the future of this country. Anti-black racism is one of the most profound and lasting scourges this nation faces, and white American women missed a chance at the beginning of the 20th century to say, "We won't vote until black women can vote. We are for women's suffrage and we are against lynching. We are for women's suffrage and we are against the poll tax. We are for women's suffrage and we are against literacy tests, etc."

When we say that this road not taken was impossible or a pipe dream, it suggests that we still live by way of the assumption that racism always has arbitrated, and racism always will arbitrate, political rights in this country.

Remembering the 19th Amendment lets us glimpse what was possible. Accepting the force of racism and sacrificing equality for the sake of political expediency were challenging in the past and remain challenges in our own time.

In looking back at all the steps and processes that were involved in women gaining the right to vote, are there lessons that we can apply today?

Racism is a women's issue. White suffragists argued that segregation, lynching, and men's disfranchisement were not women's issues. Many took the view that black women may not be able to vote, but it's not because they're women. And that means that's not a concern for this movement. So the fundamental question: What do we mean by women, and who gets to define what women's issues are?

For African American women, Jim Crow poll taxes, grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and understanding clauses are what [civil rights activist] Fannie Lou Hamer and thousands of others continued to work on until they won passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. These policies did not single out women, but they were policies, practices, and laws that disenfranchised women nonetheless. Sometimes a women's issue also affects men. There have existed between American women a philosophical divide in which African American suffragists sought their political power—including the vote—to win human rights. They sought the vote and office holding and insider status in party politics not simply to empower women. They worked to see to it that all American women—including black women—would be empowered to win human rights. This means that black women worked for the betterment of all humanity.

What resources do you recommend people explore?

The [scholarly and community research project] Colored Conventions Project is compiling the earliest black political debates, and there we find women working to win power. Look out for the memories of key black suffragists, including Ida B. Wells, Sojourner Truth, and Mary Church Terrell, among others. Read women in their own words, like on the site Documenting the American South that has digitized the slave narratives of Sojourner Truth and others.

There's a project called Women and Social Movements; I worked with them last year with a class here at Johns Hopkins to expand what we know about black women voting rights activists. Our students wrote some of the entries. I really recommend that site, particularly for people trying to get beyond the big names. It has primary sources, essays, and biographical sketches. Our students did a great job using primary research—especially in newspapers—to bring to light lesser known women.

Tell us about your upcoming book. What does it address?

The book is called Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. It is a history of African American women's politics from 1820 to 2020 with a focus on the vote. It's called Vanguard because my view is that African American women are the first—and continue to be the most committed—thinkers and activists toward a human rights vision; toward a vision of women's rights and its interest in all humans. They have always rejected racism and sexism and set a high bar that has been difficult for us as a nation to reach.

The book follows black women in their political lives and political organizations through abolition, the 15th Amendment, Jim Crow, the 19th Amendment, to modern civil rights with the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and ends with Stacey Abrams, whose work embodies the values of black women.

Once readers recognize that there were figures going back 200 years who embodied the best of our ideals in the 21st century, they will recognize that black women really were showing us the way all along. It has taken us a long time to catch up.

The book will come out in September. I'm excited because it also reflects a half-century of excellent scholarship on women's politics by dozens of historians. The book stands on the shoulders of three generations of women's historians.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged history, q+a, black politics, martha jones, women's suffrage, hopkins-votes