The question of citizenship in the United States has been fraught for as long as the country has existed, says Johns Hopkins historian Martha S. Jones.

"Citizenship has really for all our history been a very contested question. Who is in? Who is out? Who belongs? Who does not?" she told NPR's Ailsa Chang in a segment for All Things Considered on Tuesday. "For me, there's something chilling about the news today because it is in some ways so familiar."

In an interview with Axios released earlier this week, President Donald Trump said he is considering signing an executive order to remove the right to citizenship for children born on U.S. soil to non-citizens and undocumented immigrants. The action would almost certainly lead to legal challenges that could be contested in the Supreme Court and spark a constitutional debate over the meaning and guarantees of the 14th Amendment, which states that "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside."

Also see

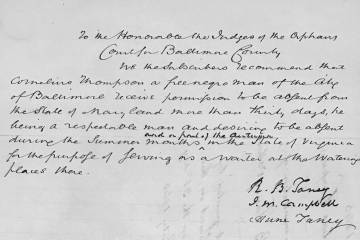

For Jones—a legal and cultural historian whose book Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America was published this summer—the question of birthright citizenship dates back even further than the 1868 ratification of the 14th amendment.

"It really originates with former slaves long before the Civil War who are now free people, are building families, are building communities, are part of the engines of economic prosperity in the country but really occupy an ambiguous status before the Constitution," she told NPR. "There was lots of debate about how to regard them, but they are clear that what they aim for, what they aspire to is birthright citizenship, a guarantee that they are permanent members of the body politic."

More from Jones' NPR interview:

Read more from NPRSitting in the 21st century, we can look back and appreciate the way that birthright means we don't discriminate based upon religion; we don't discriminate based upon national origin or descent; we don't discriminate based upon political party affiliation. And this has, I think, strengthened and given us a kind of robust and diverse democracy that has been able, to an important degree though not completely, to resist many of the prejudices and bigotries that also run through our history.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged politics, american history, martha jones