In the years before the abolition of slavery, to be a free black person in the U.S. was to live in chronic uncertainty.

Though free black communities were growing, the laws of the time were hostile, with the Supreme Court barring former slaves the right to U.S. citizenship. Meanwhile, schemes for colonization—aiming to deport former slaves to Africa, Canada, or the Caribbean—were finding receptive ears.

Image credit: Cambridge University Press

For Johns Hopkins historian Martha S. Jones, the city of Baltimore offered a fascinating perch for studying this "middle ground between slavery and freedom," she says. In her new book Birthright Citizens—published this summer by Cambridge University Press—she explores how free black people fought for legal rights during these fraught years before the Civil War.

Jones sat down recently with The Hub to talk about her findings.

What made you interested in this particular era?

Many historians had believed that the history of race and rights could be told through the notorious Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court decision prohibiting free black people from citizenship. But I was skeptical of the ability of any one case, even Dred Scott, to tell the entire story about black Americans and the law before the Civil War.

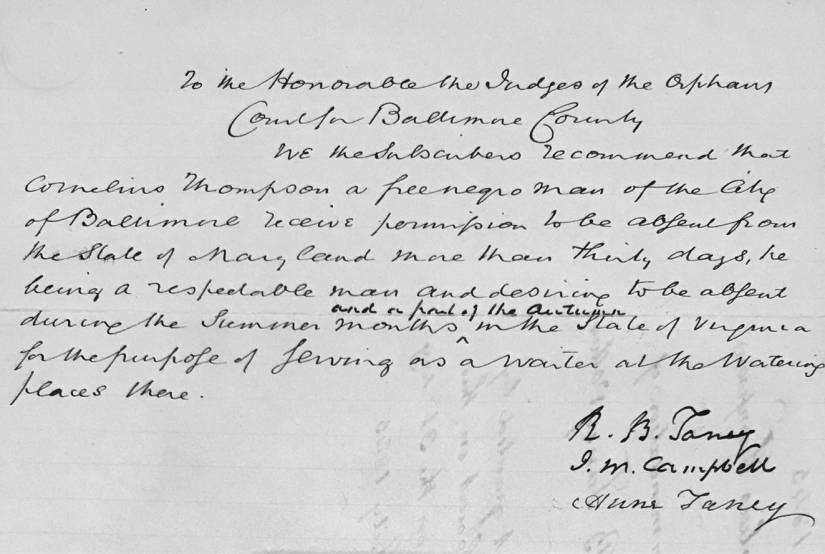

I believed there was another story, a local story. The author of the Dred Scott decision was Chief Justice Roger Taney, a Baltimorean. I found him in city records vouching for a travel permit application submitted by a freed slave named Cornelius Thompson. I knew I was onto something. Taney wasn't just a judge in Washington sitting on the nation's high bench—he was also involved in the everyday lives of African-Americans in Baltimore.

Image caption: Martha S. Jones

In Taney's view, these laws such as travel permits—termed "black laws"—were a way to achieve social control. If free black people were going to live in a city like Baltimore, he thought they should be prevented from becoming a disruptive force by inciting slaves to rise up.

Men like Cornelius Thompson, though, turned these restrictions on their head. His travel permit was his right to travel—a document with the approval and respect of influential whites, judges, and lawyers.

As I dug into archives, I found many more stories about how African-Americans exercised limited legal freedoms through everyday court transactions. Free black people went into the courthouse so that they could travel, own guns, control the education and training of their children. Records of black churches were also fascinating—they were the primary institution where large numbers of black people learned to navigate legal intricacies, in order to found and sustain their churches.

Why did Baltimore make sense as your focal point?

I was looking for a city in which I could find former slaves fighting for citizenship in their everyday lives. Free black people fled there from throughout the regions during this time, and soon it was host to the largest community of people of color in the nation.

Image caption: The travel permit issued to Cornelius Thompson by Roger Taney became a right to travel.

Image credit: Cambridge University Press

Baltimore was also the third largest city in the U.S. by the mid 19th century — a place to be reckoned with. Importantly, the city's rich courthouse archives have survived to today. That presented a unique opportunity to study, in slow motion, a smaller story about how former slaves began to claim rights.

I spent 10 years as a researcher in Baltimore before joining the Johns Hopkins faculty. I learned that this was a city that, even in present day, is very interested in its own history. After a day in the archives, I would go to a local bar or cafe, and strike up conversations—invariably, people were interested in what I was doing.

Your book explores both "colonization" and "emigration" as approaches for deporting freed slaves. What's the difference?

Both colonization and emigration were controversial. Colonization referred to schemes imposed on African-Americans from the outside and promoted by those who believed there was no future for black people in the U.S. To achieve their aims, they were willing to use coercion, enticement, and even force.

Video credit: Politics and Prose

Emigration refers to black-led movement that encouraged former slaves to leave the United States. It was always voluntary. Emigration proponents believed they were citizens, but had little hope for winning rights in the U.S. They argued that former slaves would be better off in places where they were guaranteed the full rights of citizens.

How prevalent were these concepts, beyond rhetoric?

Many historians have concluded that colonization and emigration were largely failures. Only small numbers of people ever left the United States.

But in Maryland, colonization had robust support—with the state spending money on it and local men becoming national proponents for the concept. Between 1821 and 1859, the legislature in Annapolis repeatedly proposed a forced colonization scheme. This began with Roger Taney's brother, Octavius, and continued through the eve of the Civil War.

Black Baltimoreans don't take the bait, but it did put pressure on their daily lives, with the constant threat the state might conspire to remove them.

Who was George Hackett and did you choose to chronicle the life he led in Baltimore?

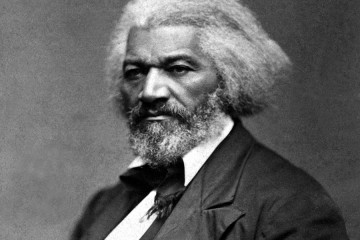

Hackett was someone who fought for citizenship with many sorts of tools across his life. The more familiar early black Baltimorean, Frederick Douglass, left the city, while Hackett was a free man who remained there.

I repeatedly kept bumping into his name in my research. Hackett's 1870 obituary noted his Navy service on the USS Constitution—the most important frigate of the American Revolution. I dove into the Navy's archives, and the story of his interesting and remarkable life came into view.

Hackett was active in local politics and churches, he was a landowner, and a founding member of a shipyard company. In 1859, he played critical role in defeating a state bill to enforce involuntary removal of former slaves. He traveled to Annapolis to confront the bill's author, Curtis Jacobs.

Birthright Citizens ends with that moment: Hackett—a man who had learned about race and rights in his church, in the Navy, and in the local courthouse—successfully helps defeat a law that would have left him without rights.

Martha S. Jones will conduct a series of talks on Birthright Citizens throughout 2018–19 in Maryland and across the country. Visit the Hub for details on her upcoming talk at Johns Hopkins taking place this fall.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged american history, law, slavery, martha jones