- Name

- Geoffrey Brown

- Geoffrey.Brown@jhuapl.edu

- Office phone

- 240-228-5618

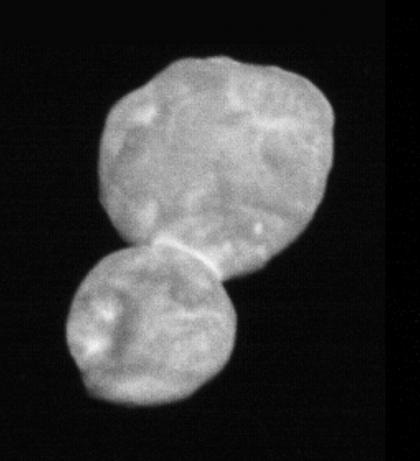

Scientists from NASA's New Horizons mission released the first detailed images of the most distant object ever explored—the Kuiper Belt object nicknamed Ultima Thule. Its remarkable appearance, unlike anything scientists have seen before, illuminates the processes that built the planets four and a half billion years ago.

"This flyby is a historic achievement," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "Never before has any spacecraft team tracked down such a small body at such high speed so far away in the abyss of space. New Horizons has set a new bar for state-of-the-art spacecraft navigation."

Image caption: This image, taken by the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager, is the most detailed of Ultima Thule returned so far by the New Horizons spacecraft.

Image credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

The new images, taken from as close as 17,000 miles on approach, revealed Ultima Thule as a "contact binary," consisting of two connected spheres. End to end, the object measures 19 miles in length. The team has dubbed the larger sphere, which is 12 miles across, "Ultima" and the smaller sphere, which is 9 miles across, "Thule."

The team says that the two spheres likely joined as early as 99 percent of the way back to the formation of the solar system, colliding no faster than two cars in a fender-bender.

"New Horizons is like a time machine, taking us back to the birth of the solar system. We are seeing a physical representation of the beginning of planetary formation, frozen in time," said Jeff Moore, New Horizons Geology and Geophysics team lead. "Studying Ultima Thule is helping us understand how planets form—both those in our own solar system and those orbiting other stars in our galaxy."

Data from the spacecraft's New Year's Day flyby will continue to arrive over the next weeks and months, with much higher resolution images yet to come.

"In the coming months, New Horizons will transmit dozens of data sets to Earth, and we'll write new chapters in the story of Ultima Thule—and the solar system," said Helene Winters, New Horizons Project Manager.

The spacecraft was designed and built at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, where it is operated and managed for NASA's Science Mission Directorate.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, nasa, new horizons, outer space