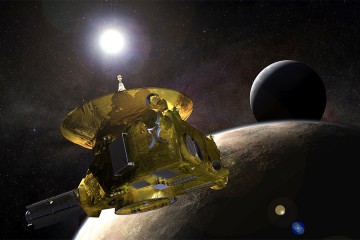

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flew past Ultima Thule in the early hours of New Year's Day today, ushering in an era of exploration of the mysterious and enigmatic Kuiper Belt, a distant region of primordial objects that holds keys to understanding the origins of our solar system.

Image caption: A composite of two images taken by New Horizons' high-resolution Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager, or LORRI, which provides the best indication of Ultima Thule's size and shape so far. Preliminary measurements of this Kuiper Belt object suggest it is approximately 20 miles long by 10 miles wide.

Image credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI

Signals confirming the spacecraft is healthy and had filled its digital recorders with science data on Ultima Thule reached the mission operations center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory today at 10:29 a.m. EST, almost exactly 10 hours after New Horizons' closest approach to the object.

"Congratulations to NASA's New Horizons team, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, and the Southwest Research Institute for making history yet again," NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said. "In addition to being the first to explore Pluto, today New Horizons flew by the most distant object ever visited by a spacecraft and became the first to directly explore an object that holds remnants from the birth of our solar system. This is what leadership in space exploration is all about."

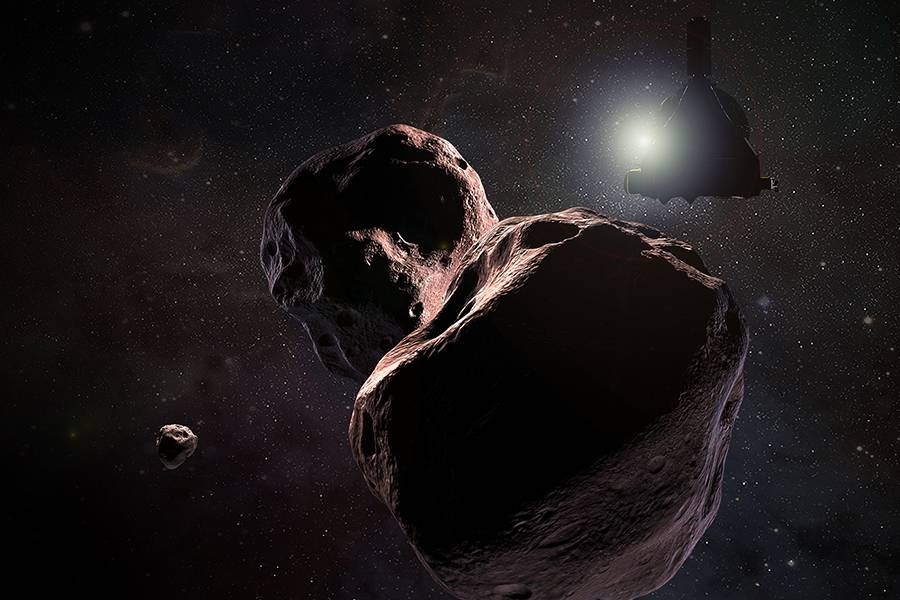

Images taken during the spacecraft's approach—which brought New Horizons to within just 2,200 miles of Ultima at 12:33 a.m. EST—revealed that the Kuiper Belt object may have a shape similar to a bowling pin, spinning end over end, with dimensions of approximately 20 miles by 10 miles. Another possibility is Ultima could be two objects orbiting each other.

"New Horizons performed as planned today, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history—4 billion miles from the sun," said principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "The data we have look fantastic, and we're already learning about Ultima from up close. From here out the data will just get better and better."

Flyby data have already solved one of Ultima's mysteries, showing that the Kuiper Belt object is spinning like a propeller with the axis pointing approximately toward New Horizons. This explains why, in earlier images taken before Ultima was resolved, its brightness didn't appear to vary as it rotated. The team has still not determined the rotation period.

As the science data began its initial return to Earth, mission team members and leadership reveled in the excitement of the first exploration of this distant region of space.

"New Horizons holds a dear place in our hearts as an intrepid and persistent little explorer, as well as a great photographer," said Ralph Semmel, director of the Applied Physics Lab. "This flyby marks a first for all of us—APL, NASA, the nation, and the world—and it is a great credit to the bold team of scientists and engineers who brought us to this point."

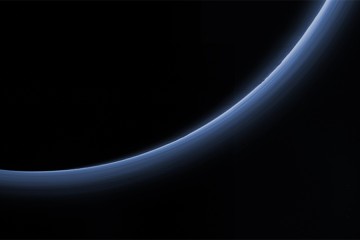

The New Horizons spacecraft will continue downloading images and other data in the days and months ahead, completing the return of all science data over the next 20 months. The spacecraft, which was launched in 2006 and reached Pluto in 2015, will continue its exploration of the Kuiper Belt until at least 2021. Team members plan to propose more Kuiper Belt exploration.

APL designed, built, and operates the New Horizons spacecraft and manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. Southwest Research Institute leads the mission, science team, payload operations, and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of NASA's New Frontiers Program, managed by the agency's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.