History, of all things, is a field where a lot of important conversations, developments, and analyses play out in the sphere of social media. For this reason, Johns Hopkins historian Martha Jones says it's just as important for professors to teach students social media savvy as it is to teach them content or research and publishing skills.

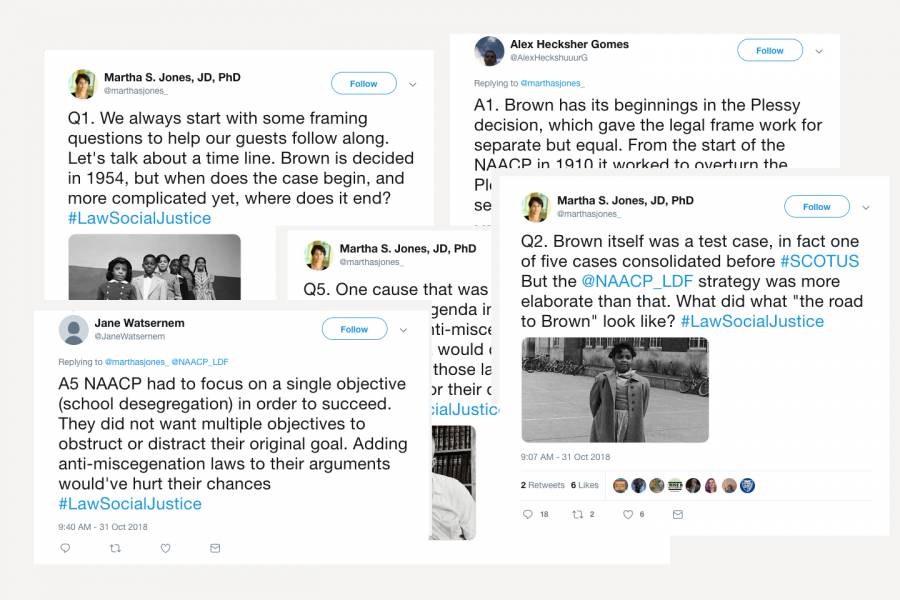

Which is why this semester, six sessions of Jones' History of Law and Social Justice course are taking the form of Twitter chats. Over the period of an hour, Jones posts 10 questions related to that unit's reading, and students—along with anyone else who happens to drop in on the chat—respond and discuss. Far from an afterthought, the chats—conducted using the #lawsocialjustice hash tag—are a central element in the course and determine 30 percent of a student's grade.

Image caption: Martha S. Jones

"I did it because I understand that students are spending increasing time in social spaces online, and I wondered what we were doing to prepare them for this environment," Jones says. "The chats are for exploring the space, to develop a sense of the medium and how it works, and a sense of their own voice and demeanor."

The format definitely makes for a different learning experience. Instead of gathering in a classroom, students sign on wherever they want. The questions are rapid-fire, with a new one popping up every six minutes. Students are required to answer each question, which means that responses often overlap, but also that all 20 can fully participate in a way not always possible in a traditional class setting. Responses are limited to Twitter's 280 characters, which encourages students to distill their thoughts, though many are also learning to "thread" their responses to allow for greater depth. And you never know who might be following the public discussion, or commenting along.

"The coolest thing is to engage with experts on particular cases or to look at sources we haven't had a chance to; it brings a different perspective to the material and how we analyze it," says senior Juliann Susas.

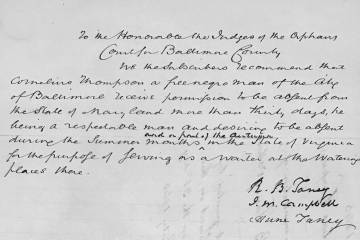

Before each noontime chat, Jones tweets an invitation to her more than 8,000 Twitter followers, encouraging them to join her students "for lunch" and including links to the pre-class readings. They often do, with engagement ranging from "liking" tweets to gently challenging students. New angles are particularly welcomed by both Jones and her students; during a September chat about the Amistad case of 1839, historian Jonathan Bryant offered insights from lawyer John Quincy Adams' personal diaries, which the class had not read, and went on to respectfully prod a student to sharpen her assertions.

"It was wonderful because as a teacher, I could come back and say, 'now let's appreciate the way in which you build historical knowledge through many kinds of sources—a diary is a way of getting at the thoughts of the person—and appreciate the way in which interpretations change when people turn to what were once new kinds of sources, like diaries,'" Jones says.

Q7. A cause lawyering analysis asks us to recognize the tensions between how advocates like abolitionists, clients like the Amistad captives, and lawyers like Baldwin and Quincy Adams see a case and a cause. What are the differences here? #lawsocialjustice pic.twitter.com/5bKpWMH0eP

— Martha S. Jones, JD, PhD (@marthasjones_) September 19, 2018

A7. The Amistad can be a case of many things (intl law, abolition, human rights) but in this case none of these are causes. The lack of cooperation from captives, abolitionists, and lawyers prevents the Amistad from being a true cause consistently in its appeals #lawsocialjustice

— Jenna Jacobs (@jennnaj_) September 19, 2018

A7 An interesting argument Ms. Jacobs. Can you elaborate? #lawsocialjustice

— jonathan m. bryant (@BryantbooksM) September 19, 2018

I think that for a true cause, the lawyer needs to be passionate about what the clients want. Here, the clients just want to go back to Africa, and the various lawyers want to either promote abolitionism, establish the US intly, or ridicule presidential behavior #lawsocialjustice

— Jenna Jacobs (@jennnaj_) September 19, 2018

Even when they win this case time and again, the outcome never truly suits all parties, which in my mind prohibits this from being an example of cause lawyering #lawsocialjustice

— Jenna Jacobs (@jennnaj_) September 19, 2018

There's another side to the chats that Jones says her students, from their current perspective as consumers of education, haven't yet fully recognized. The course's theme is cause lawyering, where lawyers use the law to advance social change. But for people who join the chats, that specialized focus may be new territory, with Jones' juniors and seniors serving as guides.

"The students discount themselves, they think they're just marching through what they know, but I believe undergrads can be producers of knowledge, and maybe this is one manifestation of that: They are teachers on Twitter and and they don't realize it," Jones says.

For some students, Twitter itself was unfamiliar; only about one-third of the class previously used the platform, mostly following news or culture. Aside from the learning curve of keeping up with the chats, students have discovered an untapped resource.

"I had an account but I never posted and was never introduced to academic Twitter before," senior Elizabeth Duncan says. "It's a way to meet people like professors, or others interested in topics I'm interested in, that I wouldn't have access to otherwise."

Since the chats follow several sessions of class discussion around the unit's reading, some students view them as a kind of quiz. On chat days, junior Miranda Bannister wakes up early to re-read her notes, then organizes them into paragraphs that could answer Jones' possible queries. "Then when the chat happens, I have fully formulated thoughts," Bannister says.

Bannister also finds herself more immersed in the reading than in courses with essay-based assignments.

"In essays, you can address just one aspect," she says. "But because we need to pull information from all the parts of the reading to answer these questions well, it motivates me more to do all the reading thoroughly."

When Jones first contemplated incorporating Twitter into this semester's course—she had done something similar before she arrived at Johns Hopkins in 2017—she gave a lot of thought to the relationship between the classroom and the larger world, especially in light of Hopkins' commitment to community engagement for the public good.

And just as the chats invite the world into Jones' classroom, she realizes that she is simultaneously inviting her students into her scholarly world, giving them a window not often available to undergrads.

"I think there is something meaningful, even powerful, about incorporating students into our context and environment as researchers and professionals, a piercing of a kind of veil," she says. "Sharing the Twitter sphere with them is inviting them to see who I follow, what I talk about, who I engage with. It's hard to know how to quantify it, but part of my pedagogical philosophy is not to leave students outside of so much of what we do. Sharing my professional space with them, inviting them into my orbit and trying to regard them as something like peers and less like receptacles of knowledge, is a good thing for all of us."

The next chat will be held on Wednesday, Nov. 14, from noon to 1 p.m. Join in by following the hashtag #lawsocialjustice.

That it for this week's #LawSocialJustice chat. Thanks for joining us and thanks to the team at @JHUArtsSciences for their support. We'll be back in two weeks to talk about legal services and poverty lawyering. Catch us then! pic.twitter.com/b8ZhGpboky

— Martha S. Jones, JD, PhD (@marthasjones_) October 31, 2018

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged history, social media, twitter, american history, martha jones