What does sporadic vegetarianism have to do with global warming? Researchers from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health traveled to Paris this week to elucidate the link between the two.

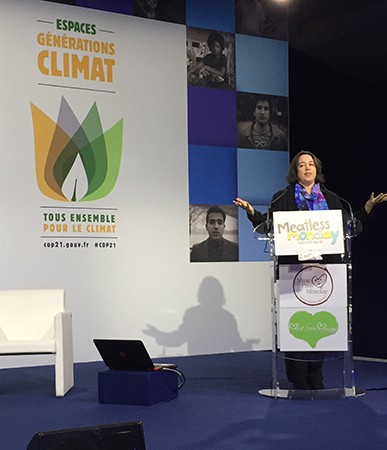

Image caption: Roni Neff of JHU's Center for a Livable Future gives a presentation at the U.N. climate change conference in Paris.

The Meatless Monday campaign, which began at Johns Hopkins in 2003, took a stage at yesterday at the United Nations' climate change conference in Paris, where world leaders at COP21 have been negotiating round the clock on a comprehensive plan to abate global warming.

Yesterday's Meatless Monday panel in Paris addressed what some experts have called a glaring void in the global warming conversation: agriculture and diet. The growing worldwide campaign calls for everybody to drop meat from their diets one day a week. Roni Neff, attending director of the Food System Sustainability Program at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, and Raychel Santo, program coordinator for the center's Food Communities & Public Health Program, were among the experts from around the world who participated in the discussion.

"Unfortunately, the connection of meat consumption to climate change is not garnering the serious attention it deserves" Neff says. "Much of the talk at COP21 is focused on government policies in energy and transportation, but we can't get from here to there without also changing diets."

Neff and Santo delivered a presentation Wednesday titled "Less Meat = Less Heat," based on evidence presented in a report they recently co-authored with CLF colleague Brent Kim and Juliana Vigorito, a Hopkins senior. For the report, titled "The Importance of Reducing Animal Product Consumption and Wasted Food in Mitigating Catastrophic Climate Change," the team gathered scientific literature from around the world and focused on the climate change-related urgency of reducing both meat and dairy intake as well as cutting down on food waste.

According to their research, livestock production contributes nearly 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions—more than the entire transportation sector. The biggest contributor is a digestive process unique to ruminant animals—particularly cattle and goats—that releases methane. Methane, or CH4, is the second most prevalent greenhouse gas emitted in the U.S. from human activities. Though methane remains in the atmosphere for less time than does the more prominent CO2, it is more efficient at trapping radiation and thus has a greater comparative impact.

Manure from livestock, feed crop production, and deforestation for pastures and crops also add up, compounding the environmental impact of raising animals for food. And wasted food is "akin to discarding all the embodied [greenhouse gas] emissions involved in its production," the Hopkins report says. On top of that, decomposing food in landfills releases more methane, the researchers said.

So how can Meatless Monday help?

"It's an important first step," says Kim, who remained in Baltimore this week. "Particularly if it's a gateway toward even greater reductions down the road."

The now 12-year-old campaign was the brainchild of Sid Lerner, known as one of the original "Mad Men" of Madison Avenue. Eager to use his advertising savvy to promote global health, Lerner teamed up with the Bloomberg School to launch the effort in 2003. The Center for a Livable Future continues to act as a technical adviser for the movement, which has since gone global. Meatless Monday programs and activities are now in place in more than 35 countries, according to the campaign's website. A Pinterest map helps track the trend .

Advocates tout benefits to health, waistlines, and wallets. And on the environmental side—the focus of the Paris panel on Wednesday—studies suggest that if everyone goes meatless one day a week by 2050, the impact would be the same as removing 273 million passenger cars from the road a year, or of closing down 341 coal-fired power plants.

The Johns Hopkins report calls for a more aggressive target—reducing global meat and dairy intake by about 75 percent by 2050, which fits in line with the Paris negotiators' goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees celsius. But the researchers acknowledge there is significant resistance to food-related policy changes for the good of the climate: Emissions from agriculture are tough to monitor, individual behavior is difficult to influence, and meat industries are powerful.

"Change is hard," Santo says. "Meat is a preferred food for most populations."

But continued growth of Meatless Monday could make a valuable dent, the researchers say.

Says Santo: "[It's a way of] shifting individual behavior and public opinion and building support for the larger policy changes that we need to make."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged sustainability, center for a livable future, climate change, food production