Visitors to the War Up Close virtual reality exhibit at the Johns Hopkins-MICA Film Centre on March 4 got an immersive look at the effects of the war in Ukraine, viewing real-world scenes of the destruction of homes, hospitals, schools, and other sites.

The exhibit is part of the War Up Close Project, which incorporates 360-degree panoramic images, drone footage, and 3D modeling to capture the devastation of the war. Johns Hopkins' MA in Film and Media program co-hosted the exhibit with Baltimore-Odesa Sister City Committee, the Saul Zaentz Innovation Fund, and Balti Virtual, providing exhibit space, student volunteers, equipment, and technical support.

Ukrainian photojournalist Mykola Omelchenko, whose work is featured in the exhibit, was on hand as visitors donned virtual reality headsets or used cardboard viewers and smartphones to navigate virtually past burned vehicles and through the bombed ruins of buildings. Before and after images of sites across the country provided stark contrast and context.

Image caption: Ukrainian photojournalist Mykola Omelchenko (right) speaks with an attendee at the War Up Close exhibit at the Johns Hopkins-MICA Film Centre

Image credit: Marly Hernández Cortés for Johns Hopkins University

Using immersive technologies to let participants explore real-world scenes is an essential part of the War Up Close Project's mission to show the reality of war in a way that cannot be denied, said Omelchenko. "It started with three friends thinking, 'How can we stop Russian propaganda?'" he told attendees. "They are shooting and destroying schools and hospitals, and people take a picture of that and [others] say, 'Well, it's the angle, you just picked an angle. It's not that bad.'" By giving the viewer a 360-degree view, "there is no angle," said Omelchenko. "Our aim is to show the world—with no angle, they can pick wherever they want to look—the reality of war."

The immersive quality of the work makes it particularly moving and powerful, said Sig Libowitz, director of the MA in Film and Media program, offered by the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences' Advanced Academic Programs division. "We've seen images of the war in Ukraine on our TV screens and online," he said. "But this exhibit puts you inside the devastation of these neighborhoods and cities, where you can't look away."

Image credit: Marly Hernández Cortés for Johns Hopkins University

With its topic and use of technology, the exhibit tied in well with the film and media graduate program, said lecturer Jason Gray, who teaches immersive storytelling and emerging technologies courses and was instrumental in bringing War Up Close to Johns Hopkins.

"It fits so well with what we are about—telling 'stories that matter,'" said Gray, whose students learn to use tools similar to those employed by the War Up Close Project to make the audience feel like they are part of the scene. "The use of space actively involves the viewer in the narrative. It's the difference between watching a film and experiencing a film."

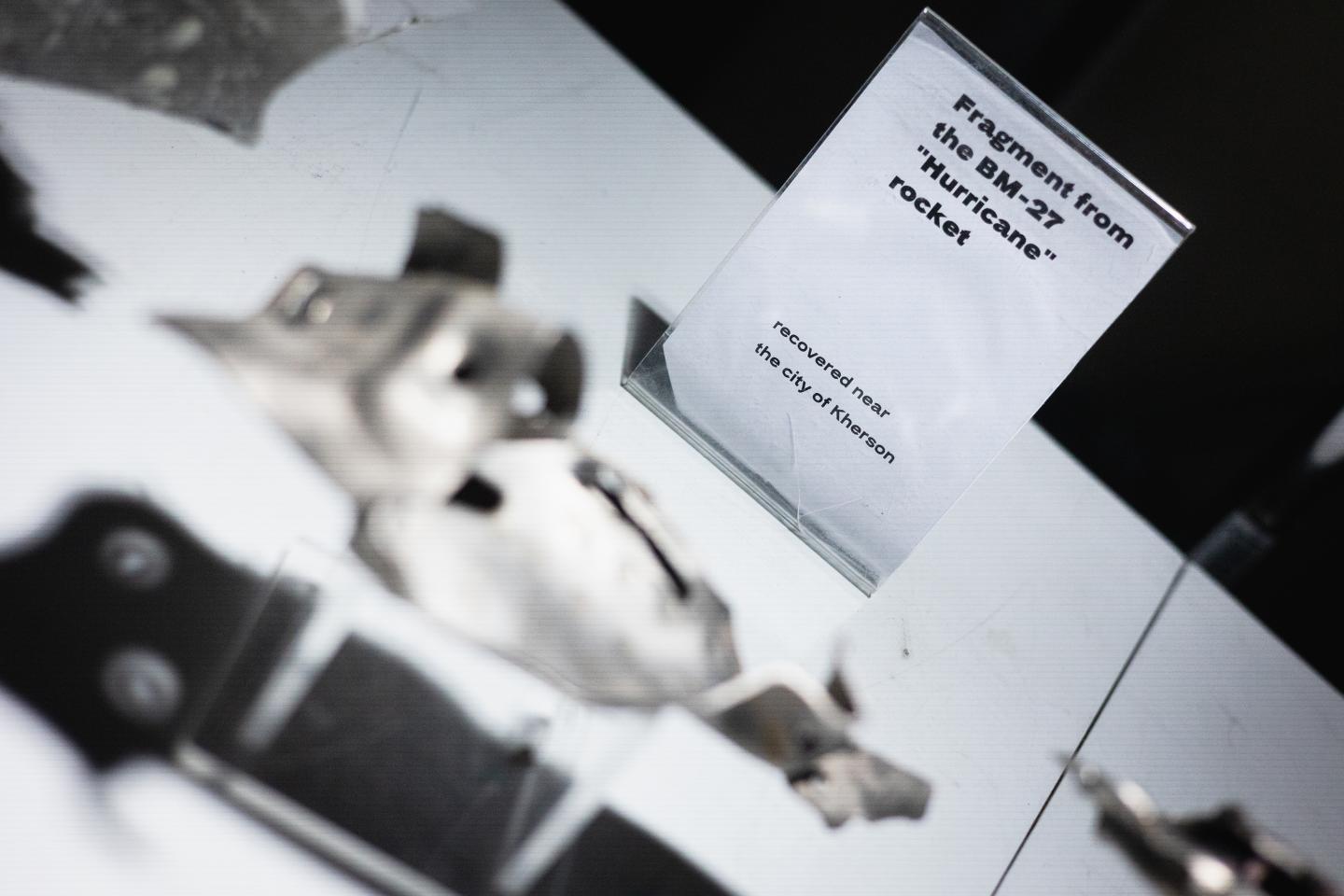

The exhibit also included a selection of artifacts from the war and links to 360-degree imagery that is viewable without virtual reality equipment. The War Up Close Project has taken the exhibit to sites around the world and will present virtual reality cardboard viewers to members of the U.S. Congress next week.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged film, advanced academic programs, virtual reality, ukraine