The coronavirus pandemic has required mankind to rise to unforeseen challenges and draw on resources they perhaps didn't know they had. Alumni of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences are no exception. Across the country and around the globe, these alums are using skills, experiences, connections, and creativity to meet unexpected needs with solutions they'd never before imagined. Here are just a handful of their stories.

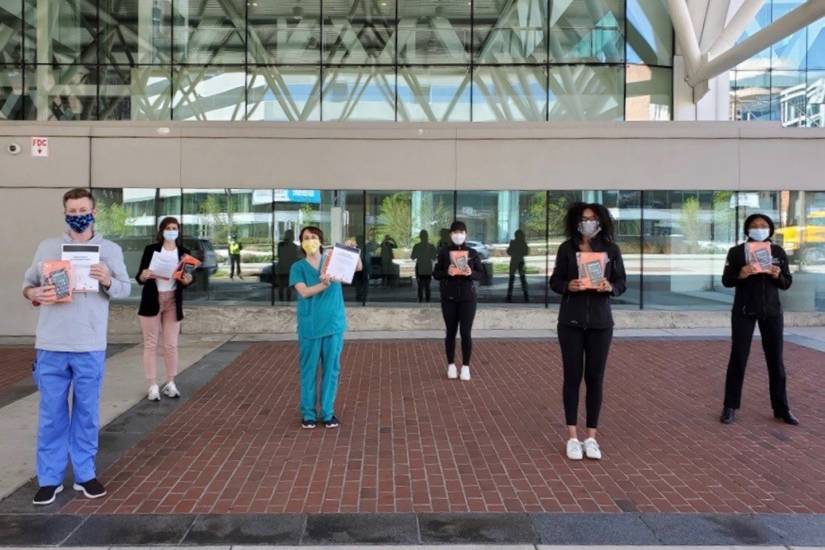

Image caption: Volunteers from the Connect for COVID-19 project show off the devices they've collected for hospital patients

Image credit: Courtesy of Annie Cho

Breaking through isolation

The idea of someone sick with COVID-19 alone in a hospital and unable to communicate with friends and family horrifies Annie Cho, a graduate of the Class of 2016. So when Cho, now a second-year medical student at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, heard about a national project collecting donations of phones and other devices and funneling them to health care facilities for patients without devices of their own, she quickly signed on to help.

The Connect for COVID-19 project was started by former Princeton undergraduates who are now scattered around the country. Group members collect donated devices, ensure they are wiped clean both physically and internally, and drop them off at hospitals and clinics that have expressed a need. Cho learned about the project from her med school friend Hulai Jalloh, who went to Princeton and enlisted Cho's support. Cho was an immediate asset to the team, with her knowledge of Baltimore from her undergrad days as a Writing Seminars major.

Often patients arrive at a clinic for testing with their family, but the clinic must turn the family away, sometimes leaving the patient with no means of communication. In a time of fear and isolation, some patients have died without being able to say goodbye to their families.

"I hope this will help family members feel a bit more at ease knowing they will have a method of communication, especially with more elderly family members or people who have special needs in terms of their health," Cho says.

While many large hospitals already offer their patients bedside iPads, many ambulatory clinics—including the new Maryland field hospital located in the Baltimore Convention Center—lack that capacity. It is those facilities where Cho and her friend are focusing their efforts. Having secured destinations ready and waiting for phones, Cho is now reaching out to individuals at Hopkins, as well as Hopkins as an institution, to solicit donations of devices and chargers. She hopes to gather enough to be able to serve Baltimore nursing homes as well.

Just sheltering in place offers a small glimpse into the intense loneliness experienced by the patients the project serves. These donated devices often benefit the elderly in particular, fewer of whom have phones of their own, Cho adds. "The longer I was in self-isolation, the more I realized what an isolating time it was, and of course I have the privilege of having a laptop and a phone and being able to reach out to friends and family," Cho says. "This is a case where even one small donation can really benefit so many patients, so I thought the project was very feasible and useful."

Getting the message

After selling his workplace operations software platform, Managed by Q, last year, Dan Teran has served as adviser and investor for other companies, including ESL Works, which developed a messaging-based app to teach English to restaurant kitchen staff who speak other languages.

In February, as COVID-19 began spreading in the United States, ESL began using the same messaging platform to provide hygiene training. Then, with Teran's help, the company shifted all its resources toward training essential frontline workers in preventing transmission of the coronavirus. With a volunteer team of a dozen former Managed by Q employees, ESL quickly scaled the training for hundreds of organizations, representing tens of thousands of workers in industries such as agriculture, manufacturing, and hospitality.

"It's been super exciting and gratifying to work on something that feels like an insurmountable problem," says Teran, who majored in international studies before he graduated from Johns Hopkins in 2010. He now lives in New York City.

When an employer enrolls in the free app—StopCovid.co—their employees receive text messages containing five-minute drills on topics including COVID-19 basics, preventing its spread, hand washing, hand sanitizer best practices, sanitizing your phone, disinfecting common surfaces, and mask usage. Content is based on guidance from the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The user-friendly platform operates through SMS and WhatsApp; no browser is required. Word has been spreading from larger companies to the smaller ones they do business with: The ordering service Delivery.com has signed on and now makes referrals to their merchant shops, Teran says.

Employers receive reports when workers complete lessons and can pass along statistics to reassure their clients about the proactive steps they're taking to ensure that frontline workers have the latest information. The app is still growing; Teran says the technology can support a million users at once.

One of the most gratifying aspects for Teran has been the messages ESL receives from frontline workers grateful for the knowledge. "Not surprisingly, people working long days and nights don't have the same knowledge of the virus as others, and so we think the people who need to know the most have the least time to educate themselves. So we meet them where they are," Teran says.

A PPE pipeline

In March, when Omar Itum started hearing from his physician friends and family members that personal protective equipment, or PPE, was in dangerously short supply at medical facilities, the New York City resident had an idea. Through beVOYAGEUR, the company he created to foster private-public partnerships and cultural understanding around the world, he's built a lot of connections over the years with leaders in governments and corporations, and he has learned a lot about their priorities and how they operate.

Image caption: Omar Itum

Drawing on those connections, Itum, who double-majored in international studies and economics before graduating from Hopkins with a bachelor's degree in 2006 and a master's degree in 2007, began using a spinoff company—OMIE AR, which brings augmented reality technology to tourism and sports—to try to fill the gap. He made arrangements to order equipment—gowns, masks, face shields, goggles, and ventilators—from more than 15 factories in China and worked out plans with his customs and freight line contacts to ship the equipment to the U.S. He consulted with a law firm to confirm that the equipment is certified by the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Itum has been talking with a few potential customers—hospital groups and city, state, and national governments and agencies. But many in those sectors remain wary on the heels of publicity about bogus products or shipments being seized at the border. One day recently, 4 to 5 million pieces of equipment were suddenly available—Itum's manufacturing contacts alert him when an order falls through, leaving them with equipment ready to ship. He notified state and city officials, but despite the ongoing shortages, no one bit.

"Having been to China and spending time within factory walls, I have a strong understanding of the operations on the ground in China, their unique culture, and the way they conduct business, which is very different from how the buyers in the U.S. operate," Itum says. "Understanding both sides of the equation well allows you to foster an operation that seamlessly integrates the two and addresses their respective needs and allows for a cohesive business operation. This is a real edge other players in the space do not have, and results in them delivering faulty and/or counterfeit products, or worse yet is when they deliver perfectly a fine product which is then seized or delayed by customs for failure to follow protocols. The real loser in that scenario is the American people."

Undaunted, Itum is slowly gathering more clients and expects the pace to pick up. He continues to hear from physicians about the dire lack of supplies. He hopes that as customers become more familiar with his company and understand the precautions it takes to vet the equipment and its origins, they will gain confidence about placing orders.

Looking ahead to a time when the pandemic may slow its spread, Itum has no plans to ease up in serving as a pipeline between PPE factories and clients. With the relationships, processes, and protocols already in place, he says his company will be well positioned to offer seamless ordering and buying through pre-vetted manufacturers.

"With the amount of work we've done, we've realized there's a much bigger solution we can pursue after all this is said and done," he says.

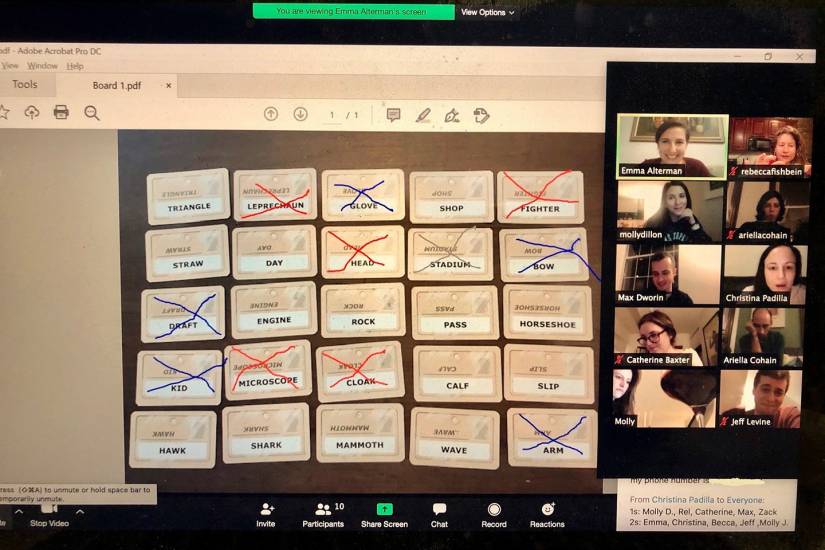

Image credit: Courtesy of Emma Alterman

The power of connection

In the second week of March, before physical distancing was mandated in states around the U.S. but when some individuals had already begun to stay home proactively, Emma Alterman realized that she might be able to shift her social life to Zoom just as her professional meetings had moved there.

"It felt like a bummer not to be able to go out and do things, especially because I really love New York in the spring," says Alterman, a sociology major who moved to Manhattan for her job as an education policy researcher after graduating from Johns Hopkins in 2012. "It was sad to be cooped up with no weekend plans, so I thought I could turn game night into something we could do virtually."

Alterman and her close-knit circle of friends made up mostly of fellow Hopkins alums would get together on the regular—or they did, back when things were "regular." Often, they would gather at Alterman's apartment for game night, where the biggest crowd-pleaser was the clue-based word game Codenames.

So Alterman, who was already familiar with most of Zoom's lesser-known features from years of using it at work, devised a way to play the game online and invited the usual gang. A bonus: farther-flung members of their circle were able to join too.

"I said to the group, 'I know you don't have plans, so I expect to see you Saturday,'" Alterman laughs.

Between playing the game and going around the digital "room" catching up, the night was such a success they've been doing it ever since. "I didn't realize until after I hung up how great I would feel, but my soul felt filled up the same way it does when I see my friends in person," Alterman says.

The offhanded idea has had larger consequences than Alterman could have foreseen. One of the friends posted an Instagram story about that first night, and a friend of hers who works for the Baltimore City Health Department saw the post and quickly borrowed the idea. At work, that friend was helping to develop an ad campaign encouraging residents to practice physical distancing. "Not all heroes wear capes. Some host virtual game nights," read one panel among a series in the finished product.

Alterman is happy that her idea has found a broad reach, and to know her circle is far from the only one making the most of uncertain times to remain connected and find positive notes where possible.

"It's such a helpless time and we feel like there's not much an individual can do, but anything you do—any good vibes you put out to the world—is good, because you make others feel better," Alterman says. "It's a good reminder that the best way to help yourself is to help others and remain connected."

Hopkins friends who frequent Alterman's game nights—virtual and otherwise—include Christina Padilla, A&S '11; Max Dworin, A&S '11; Molly Dillon, A&S '11; Rebecca Fishbein, A&S '11; Ariella Cohain, Engr '11; Jeff Levine, A&S '11; Alexandra Byer, A&S '11; Daniel Hochman, A&S '11; Jenny Smolen, A&S '13; Josh Ayal, A&S '11; and Sarah McIntyre, A&S '11.

Toward peace of mind

Francesco Clark was on the phone with the chief financial officer of his skincare company, Clark's Botanicals, the evening of March 15. Many parts of the country had just started their rapid shutdowns in the face of COVID-19, and the two were pondering what they could do to give back to the anxious community.

Image caption: Francesco Clark

"What about hand sanitizer?" they brainstormed. By the next morning, Clark was in discussions with four companies about sourcing alcohol, and just four days later, a new product was ready for sale. The company, which Clark started from his New York home in 2005, now sells the sanitizer at cost ($8.63), adds a free bottle to every regular order, and donates 5 percent of the sanitizer it makes to the Montefiore and Caldwell hospital systems in New York. Packaged in a simple, white, 4-ounce bottle, the unscented gel meets FDA requirements for killing 99.99% of germs. The company plans to continue production indefinitely to prevent price gouging.

"We thought that a little thing we could do, as a brand, to empower people is to make hand sanitizer and commit ourselves to continue making it," says Clark, who double-majored in international relations and Romance languages and graduated in 2000.

No stranger to being stuck at home—a diving accident in 2002 left him with a spinal cord injury that kept him housebound for three years—Clark wanted to make sure the sanitizer was available not only to frontline health care workers but also to anyone in quarantine. So Clark's teamed up with the skincare companies Goop and Revolve, which are selling the sanitizer for the same price. With that boost, the first run sold out in three days. Clark expects to produce at least 150,000 bottles in the long term.

Clark stumbled into starting his company while trying to improve the appearance of his skin after his injury, which left his skin unable to sweat. Once he found a solution, he wanted to share it with others with the same condition, and eventually created the business to sell his products. The sanitizer is another way he believes he can empower customers and give them a voice: Knowing that people were worried about their health and about finding sanitizer when they needed it, he saw the product as his way of helping. Along with the sanitizer, Clark's launched its #CleanHandsClearMind campaign as a reminder of the peace of mind Clark hopes to generate.

"Because we're home, we feel disconnected. But how do we work as a community to make other people feel more at ease and more confident in knowing things are going to get better?" Clark asks.

Posted in University News

Tagged alumni, coronavirus, covid-19