Veteran street photographer and attorney John Clark Mayden remembers most of the circumstances of the photos he's taken, down to the camera he was using, where he took them, the time of day, and the larger sociopolitical context of the time. He sits at a table in his West Baltimore home flipping through Baltimore Lives: The Portraits of John Clark Mayden, a collection of his photographs recently published by the Johns Hopkins University Press, looking for two photos taken at the same West Baltimore intersection.

He lands on Quenching Thirst, a portrait-oriented photograph from 1975 featuring two men, one caught with a beverage raised to his mouth, head tilted back mid-swig. "This is the corner of Lafayette and Pennsylvania," Mayden says, adding that a church is located there now but that it used to be a bar called Piccadilly. "I'm sitting on the ground and waiting for stuff to happen, and this is what happened."

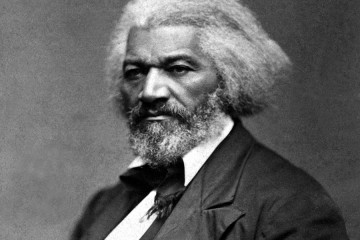

Image caption: Photographer John Clark Mayden

He flips through the book until nearing its end and stops at Bus Stop, a horizontal photo from 1976. Snowfall blankets the sidewalks, and two people stand under an umbrella, waiting for the bus, also at the corner of Lafayette and Pennsylvania. "I just wanted to show you how I took it from a different time of year and during a snowstorm," he says, before smiling a bit and adding. "I really did work that corner."

Considering the two images together highlights what makes Baltimore Lives so potent. His photos are organized visually—portraits, street scenes, people riding the bus—not chronologically. A photo from the 1970s might appear opposite one from the 2000s and be followed by one from the 1980s. This organization spotlights the consistency and clarity of Mayden's photography from the early 1970s, through his 34-year career as an attorney at the Baltimore City solicitor's office, and into retirement: capturing the rich, dynamic faces and lives of ordinary people. Time moves on and the city evolves, but flipping through the book reveals how parts of the city haven't changed all that much in 50 years.

The stories his images convey are a combination of his life, ideas, and Baltimore's own history. Those histories animate Baltimore Lives and City People: Black Baltimore in the Photographs of John Clark Mayden, the exhibition of his photos that runs through March 1 at the George Peabody Library in Baltimore. Mayden's images document a half century of Baltimore's African American people and communities, particularly the corridor of the city where he grew up, off Auchentoroly Terrace near Druid Hill Park, to downtown. He's a photographer capable of marrying his superb eye for compositions and darkroom expertise with an observant insider's understanding of the city.

Image caption: "After the Parade," 2007.

Image credit: John Clark Mayden

"When I take a picture, I think about what that image represents to me and how I can present it," Mayden says. "I try to represent it for what it is for the most part, but I'm also a romantic. So artistic romance does get in there a little bit—and some of the thoughts that I've had throughout my life come through. What I see today is influenced by yesterday."

Born in 1951 and raised in Baltimore, Mayden came of age in the 1960s. During that decade, the city's population began dwindling from its peak of nearly a million people, owing to a combination of postwar deindustrialization, suburbanization, and economic crises, factors that dramatically reshaped city life. Mayden talks about getting involved in the civil rights and anti-war movements, attending an activist church, getting into sports, and learning to swim at the Druid Hill YMCA. "Where I grew up, there were a lot of people, and I was always inquisitive about how people looked, what they said, what they did, and what they wanted to achieve," he says. "Black people were concerned about having an equal opportunity, and my concern for people was what I really was motivated by." Now in his 60s, Mayden retains the physical composure of the athlete he was in high school, paired with the discerning eye and mind of an artist who started documenting street life in 1970.

Mayden took up photography in earnest while working as a TV reporter for the local ABC-affiliate, WMAR-TV. Drawn to the station's still photographers, he would ask them questions and chat with the darkroom crews. He bought a Nikon and hit the streets, walking the city. "There was a lot of activity going on around Pennsylvania Avenue, which was a social area for a lot of people during the segregated era," he says of Black Baltimore's legendary arts and entertainment hub, former home to nightlife hot spots such as Club Casino, Ike Dixon's Comedy Club, Gamby's, the legendary Royal Theatre, and the still-going Arch Social Club. "I would hear stories about that, and it was colorful to me." The Maryland Department of Commerce named the area the Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts and Entertainment District in 2019.

The timeless quality of Mayden's photography makes it a vital addition to the Africana Archives Initiative, an ambitious partnership between the Johns Hopkins University's Sheridan Libraries and Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts. The initiative aims to grow a collection of African American primary sources with a special emphasis on local history and culture. In 2017, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor Lawrence Jackson, the director of the Billie Holiday Project, and Gabrielle Dean, the Sheridan Libraries' curator of rare books and manuscripts, began organizing meetings with local archivists, librarians, and private collectors to talk about the state of local and regional African American archives. Kali-Ahset Amen, the Billie Holiday Project associate director and assistant research professor of sociology, joined these periodic conversations after she arrived in early 2019.

Mayden, who donated a portfolio of 100 photographs to the archive, got involved with the Billie Holiday Project through Jackson, a Baltimore native who was friends with Mayden's nephew. In the 1980s, Mayden and his wife rehabbed a rowhouse they lived in on Linden Avenue in Northwest Baltimore, and it included a small gallery for his photos, which Jackson remembered.

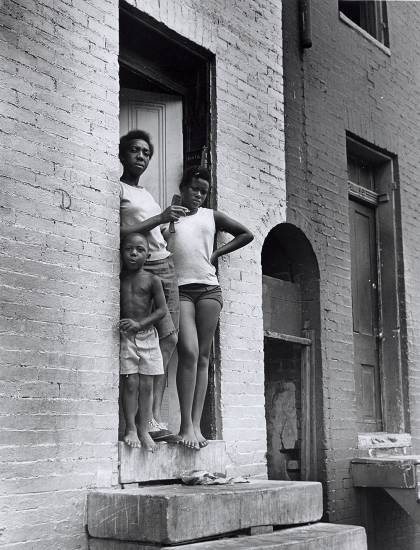

Image caption: "Family," 1972.

Image credit: John Clark Mayden

Reaching out into the community is how museums and archives find the objects they use to tell the stories of history, especially from communities underrepresented in the historical record. In his recent memoir A Fool's Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump, Lonnie Bunch talks about how the museum built its collection. Bunch, the founding director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and colleagues went on an Antiques Roadshow–inspired Save Our African American Treasures tour of the country in 2009, stopping in 15 cities and inviting people to bring out family heirlooms and the like. The museum estimates that more than half its 37,000 artifacts came from such personal donations. Jackson was able to reach out to a personal connection to tap into Baltimore's local history, and the ongoing archival project that archivist Dean and the Billie Holiday Project started seeks to build collaborative relationships with local repositories documenting the lives of African Americans in the area.

Baltimore Lives compiles Mayden's images into a gorgeous photographer's book. City People, curated by Dean and history graduate student Christina Thomas, puts a selection of those works in conversation with photos from the Sheridan Libraries' archive, situating Mayden in a larger context of local history and African American photography.

Not that his photos aren't capable of telling larger stories all by themselves. On page 93 of Baltimore Lives is a 1971 photo Mayden titled Relaxin'. It features a man chilling out on a sofa that faces a table and three chairs, all of which are located outside in a clearing. He wears a short-sleeve Oxford shirt, unbuttoned; pants; and appears to be shoeless. The furniture has seen better days. In the background are trees, the brick face of a nearby building, the uncut tall brush that takes over vacant city lots, and the backside of a large interchange sign.

Also see

It's a combination of unruly nature abutting urban life that seems strange until you see Mayden's location note: the Highway to Nowhere, that 1.3-mile stretch of abandoned interstate for which the city demolished 971 homes, 62 businesses, and a school in the 1970s, displacing nearly 3,000 residents and forever dividing the West Baltimore neighborhoods of Harlem Park, Poppleton, and Franklin Square.

Mayden recalls walking through West Baltimore and coming upon this scene. "I was uncomfortable because it's an abandoned place, yet we're in a city," he says, looking at the photo. "It was my first exposure to urban renewal, what it was doing, the acquisition of property."

When the stories of Mayden's photos return to him, he's not only thinking about what happened then but how his photos continue to tell us about city life today. "My man here is just relaxing," Mayden says, looking at the photo. "He took found objects, made it home, and hung in there until they put him out. And so I'm trying to understand, in '71, something that later was explained to me, what really happened here. That leads me to start thinking about, well, how about some of the projects that we're doing now? And that leads to a conversation for another day."

A City of Neighborhoods Celebration, set for 1-5 p.m. on Sunday, February 23, will mark the closing of the City People exhibition. The afternoon will include performances, an open mic, and family activities centered around Baltimore's neighborhoods.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged history, exhibits, photography, black history month