Frederick Douglass intended to make the journey at night, with five other enslaved men, stealing a log canoe to paddle north along the Chesapeake Bay.

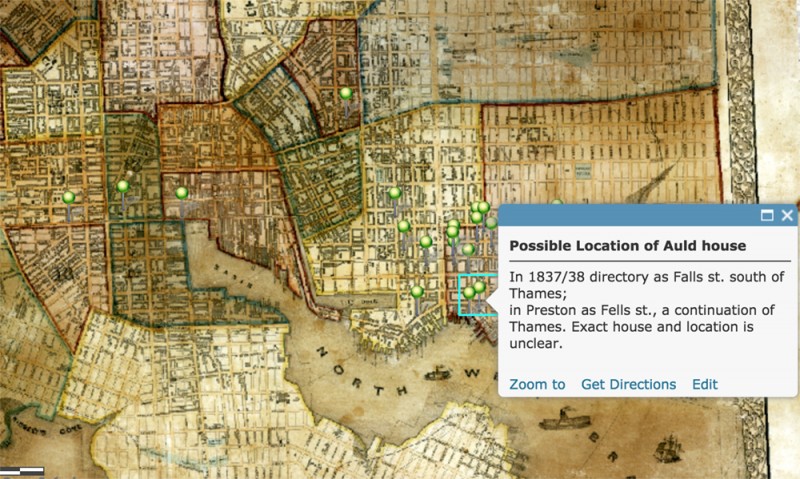

Image caption: Frederick Douglass

Image credit: George Kendall Warren / Wikimedia Commons

When a group from Johns Hopkins sailed upon those same waters last spring, they recognized how audacious it was for the young Douglass to imagine such a coastal escape in 1836.

"It was challenging for us, even with instruments and knowledge and pretty good sight," JHU Professor Lawrence Jackson said of the sailing trip his class took last May along Maryland's Eastern Shore.

Of course, Douglass never set foot in that canoe. Instead of rowing toward freedom, he landed in a jail cell in Easton. He wouldn't try again for another two years, boarding a train from Baltimore and escaping successfully to the north.

For Jackson's class, the time in Maryland before that escape commanded the most interest—Douglass' formative years, before he became the world-famous abolitionist, orator, and writer. Students in the graduate English seminar "Mapping Frederick Douglass" researched and visited regional sites of significance in the young slave's life, from the Eastern Shore plantations to the streets and shipyards of Baltimore.

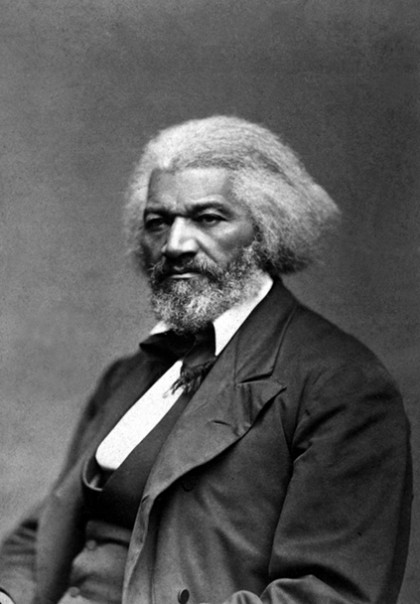

Working with the Maryland Historical Society, the four students combed archives, old newspapers, and census records to trace Douglass' pathways in the 1820s and '30s. Then, with JHU's Sheridan Libraries, they used the ArcGIS digital mapping platform to construct a visual narrative.

In the end, they had a collection of four digital "story maps."

Image caption: A visual from the Mapping Frederick Douglass project shows the possible location of the Auld family home, where Douglass worked as a slave on loan as a child

Image credit: Lawrence Jackson / Mapping Frederick Douglass

Jackson, who joined Hopkins last year as a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor in English and History, said he imagines the project morphing into a larger resource for "broad public consumption"—for use in museums and schools, for example. Last semester his students shared the project with classrooms at Baltimore City College and Morgan State University. And in February Jackson will present the maps at the 200th anniversary celebration at the Douglass Museum and Cultural Center in Highland Beach, Maryland.

For now, the Hopkins community has access to the maps via the ArcGIS system through the Sheridan Libraries. For those with JHED logins, the available maps are:

- Wye House/Great Farm 1818-1824 (Alexandra Lossada)

- Frederick Douglass in Baltimore, 1826-1833 (Alexander Streim)

- Douglass on the Eastern Shore, 1833-April 1836 (Evan Loker)

- Frederick Douglass in Baltimore: 1836-1838 (Joseph Giardini)

By design, the maps are richly layered with biographical snippets on Douglass and historic artifacts from the era.

One map that captures Douglass' time as a child on the Lloyd plantation in Talbot County includes an 1827 inventory listing the monetary value of several of his family members—and of Douglass himself, valued at $110 at age 9.

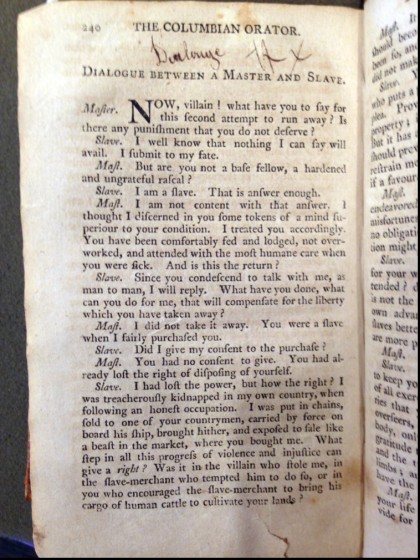

Image caption: After teaching himself to read, Douglass bought a copy of The Columbian Orator, a collection of patriotic speeches that stirred his first ambitions for freedom

Image credit: Lawrence Jackson / Mapping Frederick Douglass

Another map shares a yellowed page from The Columbian Orator, a collection of patriotic speeches that stirred Douglass' first ambitions for freedom, at age 12, as he worked as a slave on loan in Fells Point. He purchased the copy, after teaching himself to read on the sly, from a book shop at 28 Thames St.

Douglass later returned to Fells Point as a teenager, finding greater mobility as he earned wages as a caulker in the neighborhood's shipyards. The map of this period points to Happy Alley as one meetup site for a group of freed black men Douglass mingled with, the "East Baltimore Mental Improvement Society."

"I tried to include pathways known to Douglass, to track his movement in the city," grad student Giardini said of his work.

The same map also pinpoints the location of the station—at Pratt Street near Light Street—where Douglass boarded his Philadelphia-bound train to escape, on Sept. 3, 1838.

Jackson said the inspiration for "Mapping Frederick Douglass" came from digital maps he'd seen tracing General Sherman's march through Georgia and a New York Times feature tracing Harriet Tubman's path to freedom on the Eastern Shore.

In addition to readings of several different versions of Douglass' biographies and autobiographies, Jackson's class was heavy on excursions, including trips to Annapolis and New York City.

The semester culminated in the sailing trip last May, for which Jackson and two students spent a full day and night aboard a chartered boat, navigating waterways and coves of the Chesapeake that formed the backdrop of Douglass' young life.

One map from the project charts this region, pointing to the imagined canoe escape path in 1836. It includes a quote from Douglass's autobiography, in which the future abolitionist vows that the year "should not close, without witnessing an earnest attempt, on my part, to gain liberty."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged history, sheridan libraries, maps, lawrence jackson, frederick douglass