The images are branded into our historical consciousness, but for those who remember watching the live footage on July 20, 1969, it was surreal and heart-stopping: A human being, for the first time, walked on the moon.

It was 10:56 p.m. that Sunday night when Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong hopped off the ladder of the Eagle module to take his first steps on the moon's powdery surface. Buzz Aldrin joined him about 20 minutes later. This was the peak of Walter Cronkite's multi-hour coverage of the Apollo 11 mission, which had an estimated 650 million viewers around the world glued to their television screens.

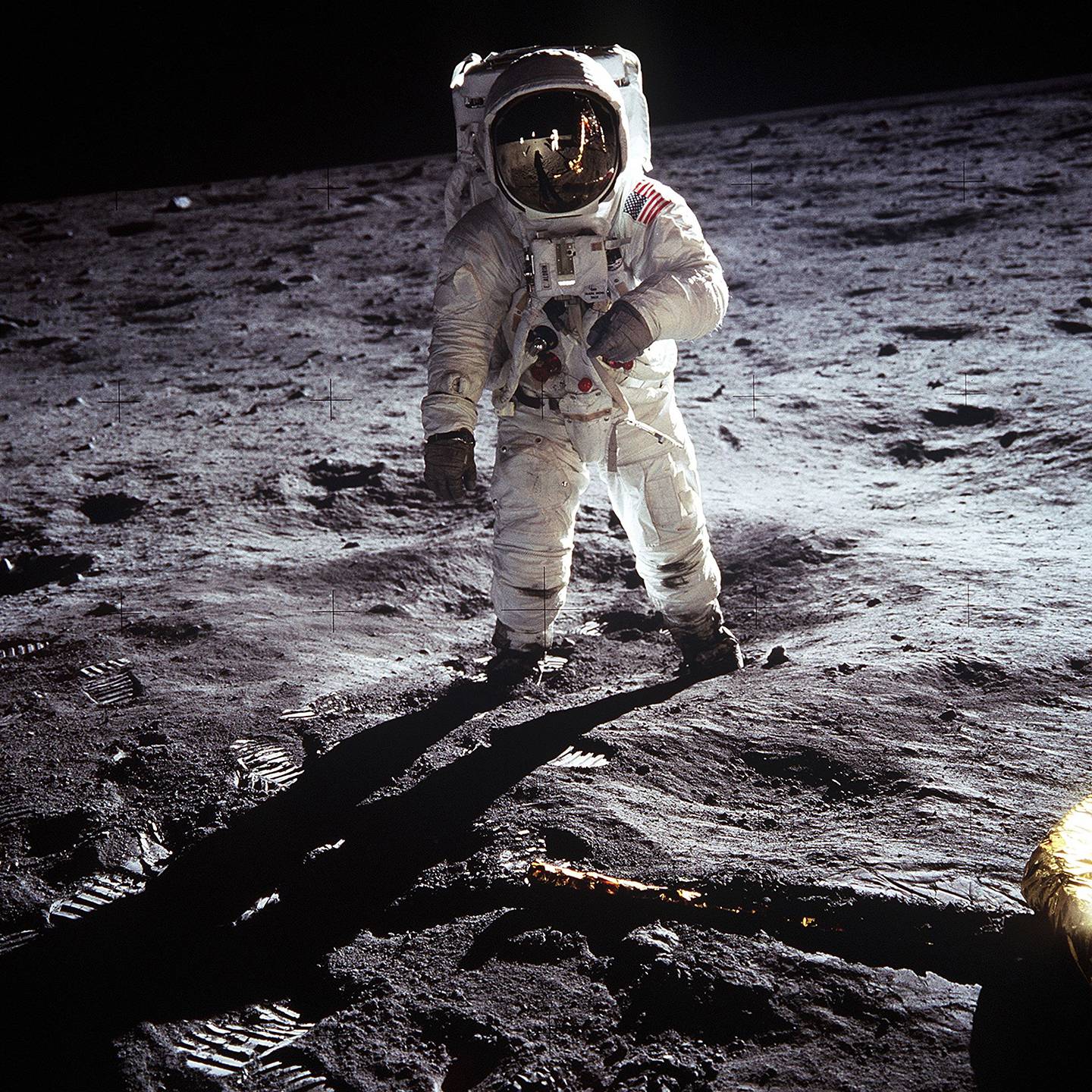

Image caption: Buzz Aldrin walks on the moon on July 20, 1969

Image credit: NASA

With the 50th anniversary of those historic first steps on the moon approaching, the Hub reached out to several Johns Hopkins faculty members and asked them to share their memories of that awe-inspiring time.

Chuck Bennett

Director of Space@Hopkins and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of physics and astronomy

In the early days, every rocket launch and astronaut landing ("splash-down") was of compelling interest. This time in 1969 was even more special. My family was gathered in front of the TV in my parents' bedroom. It was tuned to CBS News, and on screen was the most trusted man in America, Walter Cronkite. Astronauts were about to attempt to land and walk on the moon for the first time.

There was nervous silence, great tension. Then we heard, "Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed." Everyone felt the release of tension that Cronkite's reaction showed. Exhale now, breathe, eyes water. Then, about six and a half hours later Neil Armstrong left the landing craft and set foot on the moon. His "giant leap for mankind" seemed amazing to me—a human was walking on an object that I viewed through my backyard telescope.

There was great and well-deserved pride for our country's accomplishment. In an age of deep divisions over the Vietnam War (I was nearing draft age), the accomplishment was a unifying event. Optimism feeds accomplishment and accomplishment feeds optimism. President Kennedy had said that the country would do it and we did. The reason was geopolitical. The U.S. was behind the USSR at the time and needed to catch up, and to do so on a world stage with a grand effort. We also needed to show ourselves and others that we were still capable of doing great things as a nation. NASA was assigned a huge budget.

When Alan Shepard hit the golf ball on the moon in 1971, he illustrated a basic problem: Now that we made it to the moon, we had nothing to do. The geopolitical spectacle was accomplished. Now space flight is routine. We don't even know at any given time how many astronauts are in space or what they're doing, nor do most people care.

Yet, people love to see pictures from the Hubble Space Telescope, and they loved to see pictures from the Mars rovers. Apollo 11 was a great feat of engineering. The Hubble and Mars rovers were primarily for doing science. Apollo 11 was compelling because there were people involved. Our most productive scientific space missions leave the people on Earth and operate by remote control for much less cost. Meanwhile, our astronauts are stuck in Earth's orbit.

The space future includes choices that balance engineering exploration against science goals, and humans versus robots. Now commercial interests want to monetize the moon and asteroids (with government subsidies). Some look back to the moon while others yearn for landings on Mars. And others, like me, yearn to use our optimism and engineering prowess to reach further out into the universe, into the unknown.

Ed Scheinerman

Vice dean for graduate education at the Whiting School of Engineering and professor of applied mathematics and statistics

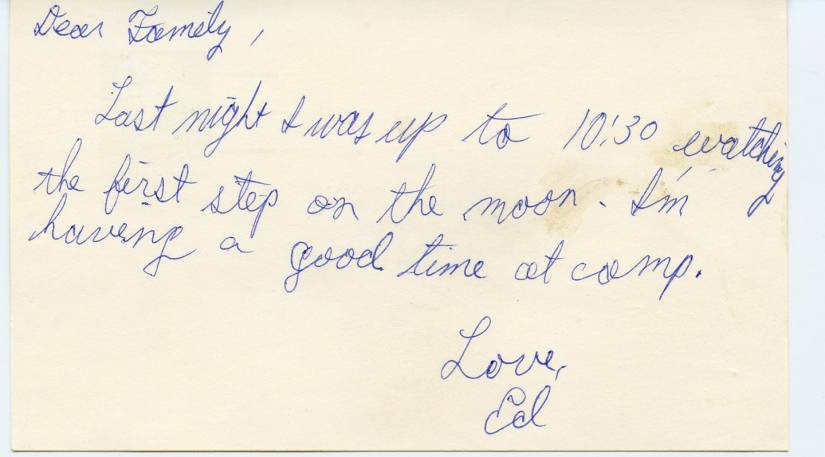

Image caption: "Dear family, Last night I was up to 10:30 watching the first step on the moon. I'm having a good time at camp. Love, Ed."

I found this postcard in a big pile of letters from camp that my parents saved. I was 12 years old at the time of the moon landing, spending my summer at Camp Baco in the Adirondacks. I remember the whole camp getting together for the occasion, watching on a black-and-white TV.

As a kid I watched every space launch I possibly could; I had a standard hero worship of astronauts. In the '60s every launch was thoroughly televised, they could be very long broadcasts, and I'd be glued to the screen. I remember watching the early Mercury launches and being devastated by the death of astronaut Ed White in Apollo 1.

Later in my life, as I was about to turn 40, I thought, "What am I going to do for my midlife crisis?" (I didn't actually have one, but felt like I should indulge nevertheless.) On a lark I filled out all the paperwork with NASA to become an astronaut. It was a whim. I heard back from them later: Of course I got rejected! My wife's greatest fear was that I'd get accepted.

Around 2000, I spent a year away from my normal post at Hopkins—through a grant that puts mathematicians in different environments—and embedded myself in the Department of Mechanical Engineering. One professor was doing experiments with NASA on the KC-135 plane, also known as the vomit comet. I got the chance to get inside and experience zero gravity: 30-second intervals of wonderful weightlessness. And I did not vomit!

Rosemary F.G. Wyse

Alumni Centennial Professor of physics and astronomy

As a little girl growing up in Dundee, Scotland, I was fascinated by science and science fiction—part of the generation growing up with the original Star Trek and Dr. Who.

I was 12 years old at the time of Apollo 11, and I remember gathering with my family to watch the moon landing on television. There was a sense of wonder and excitement that night that has stayed with me over the decades since. I still thrill at the archival footage.

The Apollo missions certainly played a major role in stimulating my interest in the physics of the world around me, and in my subsequent career in astrophysics.

Harry K. Charles Jr.

Associate dean at the Whiting School of Engineering, program manager and group supervisor of the APL Education Center

I was 25 years old at the time and working on my PhD in electrical engineering at Johns Hopkins. This was the very same month I met and started dating the woman who, I didn't know at the time, would later become my wife.

I'd started off on the wrong foot with Virginia—she was planning a date with a friend of mine, and I made some wise-guy comments on the side. She responded with a cold stare. A couple days later I ran into her in the Eisenhower Library (she was also studying at Hopkins, earning her Masters of Education), and I asked her out for a cup of coffee. Our first date was July 10, 1969, and we were engaged by that September.

On the day of the moon landing, Virginia and I went on a date to a local fair in Baltimore then I went home to study. I lived with roommates in an apartment in Wolman Hall and had a black-and-white TV with rabbit ears in my bedroom. That's where I watched Neil Armstrong walk on the moon.

Seeing it was surreal—you could hardly believe it was true, and yet there it was. People were talking about it for a long time before and a long time afterward. It's one of those seminal events in life where you remember exactly where you were.

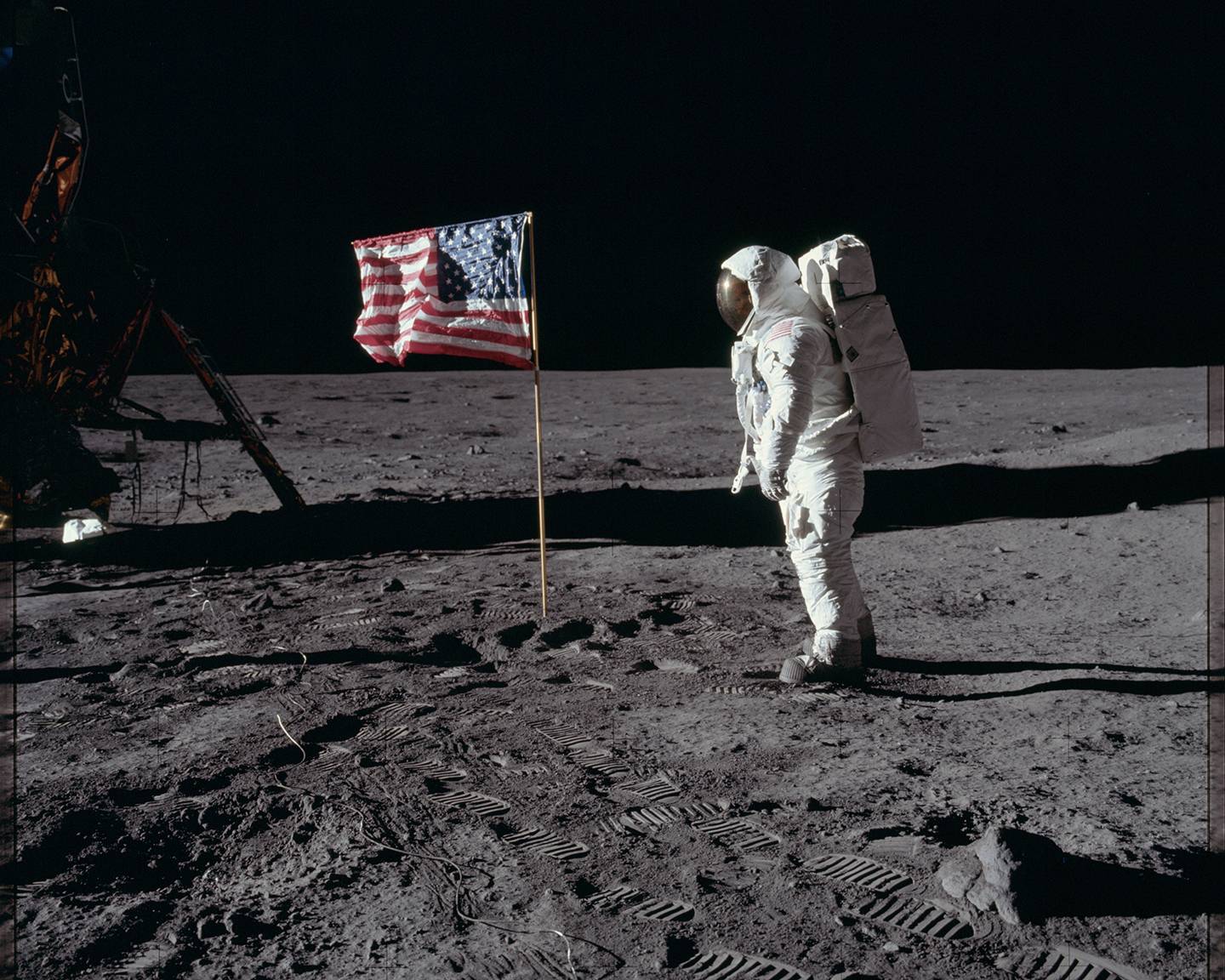

Image caption: Buzz Aldrin salutes the American flag on the moon in this iconic image from the Apollo 11 mission.

Image credit: NASA

I was particularly interested in space because I'd worked with NASA as a co-operative education student during my undergraduate program at Drexel. Following graduation, I spent two summers down at Goddard [Space Flight Center], tracking satellites. Even though we weren't in Houston, the center was very excited about what was going on with Apollo 11.

For my wife and I, the Apollo 11 anniversary comes right after the 50th anniversary of our first date. Last week we were down in New Orleans celebrating that. And next March, we'll be celebrating the 50th anniversary of our wedding.

Barbara Landau

Dick and Lydia Todd Professor of cognitive science

My reminiscence is quite personal and poignant. When I grew up in Princeton, New Jersey, my father was a physicist who worked on some of the earliest satellites developed for the RCA Corp. At the time of Apollo 11 he had recently retired early due to advancing multiple sclerosis.

I was an undergrad at Penn but was home in Princeton at the time and watched the landing with my dad. I was thrilled. He cried, understanding far more than I did what an accomplishment it represented. I have never forgotten.

Chia-Ling Chien

Professor of physics and astronomy

At that time I was living in an apartment in Pittsburgh as a graduate physics student at Carnegie Mellon. My roommate Richard and I didn't have a TV, so the evening of the moon landing we borrowed an ancient one from a friend of my parents.

The TV contained vacuum tubes, which wouldn't work at times unless physically hit. So my roommate and I took turns hitting this poor TV for several hours in order to watch the entire Apollo 11 landing. Despite all the interruptions, it was an incredible, unbelievable sight that I'll always remember.

Posted in Science+Technology, Voices+Opinion

Tagged space, outer space, american history, space@hopkins