- Name

- Geoff Brown

- Geoffrey.Brown@jhuapl.edu

- Office phone

- 240-228-5618

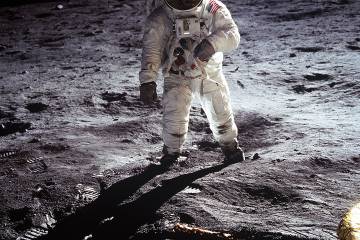

It is an indelible moment in American history: "That's one small step for man," Neil Armstrong's voice crackled through television sets worldwide, as he descended from the Apollo 11 lunar module, "one giant leap for mankind."

An estimated 650 million people around the world watched Armstrong touch his feet to the moon's surface on July 20, 1969. The grainy, black-and-white images became some of the most recognizable TV footage in history, a broadcast made possible in part by the work of the Space Systems Application Group at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

"Our job was solving quick, short problems for Apollo," says Gary Whitworth, an APL engineer who joined the lab in 1966.

Whitworth was part of a small team assigned to work out the kinks in NASA's Slow Scan Television Camera, which transmitted video at 10 frames per second—compared to the 30-frames-per-second norm of commercial television in 1969. Interference from other crucial mission signals that needed to be sent back to Earth turned the image to a snowy, line-streaked mess.

"The transmission still would've been there [without our work], but you wouldn't be able to see the picture very well," Whitworth says. "We reduced the interference by about 20 dB, a 98% reduction, so the TV was at least watchable."

Video credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

Ironically, Whitworth—one of the people responsible for the television transmission of such an iconic moment—doesn't recall exactly where he was when he watched the broadcast of the moon landing. But 50 years later, his pride in his contribution has not dimmed.

"NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center would come to our group at APL to solve [particularly difficult] problems, and this was one of those problems that popped up," Whitworth said. "If we solved it, we were heroes. If we couldn't solve it, well, nobody else could solve it either. You couldn't lose in that game.

"It was very rewarding work, and I think it spoiled me from that time on. I still did interesting work, but it just was not as exciting as those early Apollo days."

Whitworth worked at APL for the better part of 32 years before retiring in 1997, just before his 56th birthday. He contributed to a multitude of projects, including developing the radio frequency parts of the timing receiver, technology he says is a precursor to what we know today as GPS.

Of his contributions to the historic Apollo 11 broadcast, he notes nonchalantly that he may have talked about it with just one or two of his five children, 11 grandchildren, or seven great grandchildren.

"It was my job, it was something we were supposed to do," Whitworth says. "I probably mentioned it to a few people—maybe other retirees when we get together, slapping on the back and joking about that time—but for the most part it was just one of those tasks."

As the 50th anniversary of the lunar landing approached, Whitworth found the medal NASA commissioned for all who participated in the mission in a significant way gathering dust on a shelf in the office of his Clarksville, Maryland, home. On the medal's front are the Apollo 11 astronauts—Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins—and on its back is the lunar module with the date of the historic event.

Now that he's given in to some nostalgia surrounding the anniversary of the lunar landing, Whitworth says the medal may find a more prominent display spot.

"I'll put it a little closer to the front of the shelf," Whitworth says with a chuckle.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, nasa, outer space