Augustine Herrman spent more than 40 years doing business up and down the Atlantic seaboard of the New World in the 17th century. He was Bohemian by birth, and around 1640 the Dutch West India Company brought him to New Netherland, where he soon became a skilled trader and colonial diplomat. Over the next 20 years, he did business with the New Englanders, the Native populations, and especially with colonies lining the Chesapeake Bay—New Sweden on the Delaware River, the English in Virginia and Maryland.

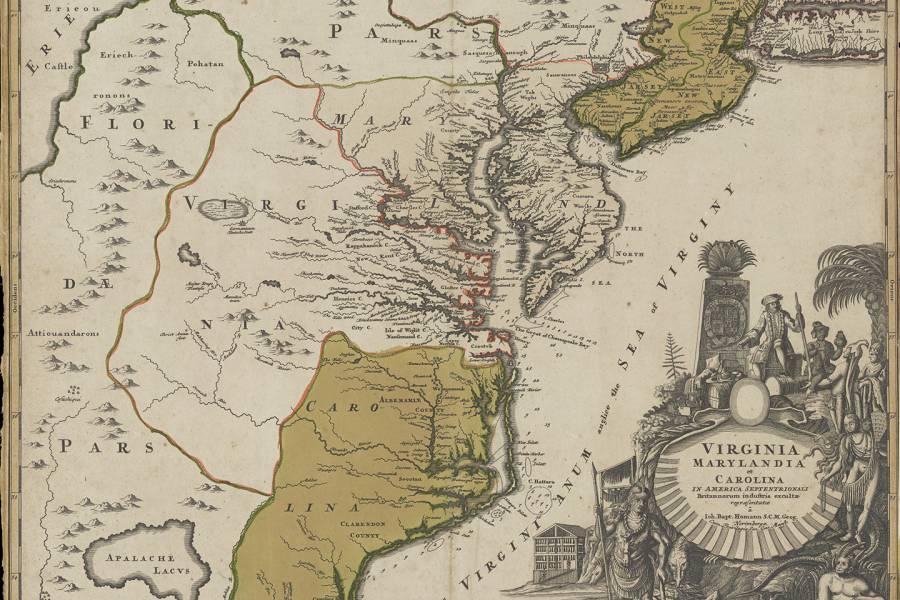

When a land dispute between the Dutch and English threatened to disrupt trade, he told Lord Baltimore that he could draw a new, better map of the Bay in exchange for some Maryland land. And as Towson University Associate Professor of history Christian Koot writes in his recent book, A Biography of a Map in Motion: Augustine Herrman's Chesapeake, Herrman's Virginia and Maryland as it is Planted and Inhabited not only became one of the most important 17th-century maps of the area, it suggested a future. The Chesapeake as rendered and imagined by Herrman was more informed by his trading experience than any allegiance to any singular European country, pointing toward an idea of the New World not split up by their colonial ties but united by their common business interests.

Koot delivers a free book talk at the George Peabody Library today as part of the Maryland, from the Willard Hackerman Map Collection exhibition currently on view in the library's gallery. And his scholarship and understanding of Herrman's map nicely complement the exhibit's broad exploration of the use of Baltimore city and Maryland state maps over time.

The exhibition—co-organized for the Sheridan Libraries by Paul Espinosa, curator of the Peabody Library, and Jim Gillispie, Geographic Information Systems librarian and curator of maps—not only spotlights Hackerman's map collection, it shows how maps have shaped people's understanding of the city and state, and how current faculty are turning to them for research projects today.

"We want to show that these maps don't live in isolation," Espinosa says. "They don't just live on a wall. They have a history. The collector has a history."

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Sheridan Libraries

Willard Hackerman was a 1938 graduate of the School of Engineering who went on to become the CEO of the Whiting-Turner Contracting Company, the Baltimore-based firm that, under his leadership, played a role in building or renovating a great deal of Baltimore's urban landscape: Harborplace, the Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, M&T Bank Stadium, and more. He started collecting maps of the city and state in the 1980s, and by 1998 he had put together such a thoughtful, rare collection of maps from the 16th through 19th centuries that it was featured in an exhibition at the Maryland Historical Society. He died in 2014, and his map collection was donated to the Sheridan Libraries by his wife, Lillian P. Hackerman, in 2016.

The collection tells a variety of stories over time, about how people understood the Chesapeake Bay, about how the city should be laid out, about whom the land belonged to. Espinosa points to official insignia that appear on two maps of the bay, one from 1635, the other from 1671. In the former, the coat of arms of King James I is placed above that of Lord Baltimore, "so you can see who's subservient to whom," Espinosa says. "By 1671, the royal coat of arms has disappeared and now you get this big, flourishing Baltimore coat of arms. So you can see we're already starting to gesture toward the American Revolution in many ways."

For Maryland, Espinosa and Gillispie display various maps from the collection alongside prints and books from the same era, many of which provide street scenes of the city. When they are seen together, it's like toggling between Google's maps and street view, each perspective providing a different set of information about a place. "The maps show what was there," Gillispie says. "The print makes the map come alive."

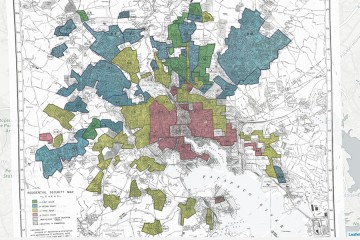

Faculty members are turning to these maps for their ability to contextualize the past as part of their research. History Professor Mary Ryan used some of the maps from this collection in her upcoming book Taking the Land to Make the City, which explores the city-making processes of Baltimore and San Francisco from the 18th into the 19th centuries. Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History Lawrence Jackson had his students use Baltimore city maps to help them understand what Baltimore was like when jazz singer Billie Holiday and abolitionist and writer Frederick Douglass lived here. And history Professor N.D.B. Connolly used the redlining Residential Security Map of Baltimore Md. from 1937 as part of the Mapping Inequality project on which he collaborated.

Gillispie says there are many ways that old maps can still speak today by combining them with modern geo-referencing technology.

"When I look around Baltimore, I always wonder, Well, why was a road built here?" he says. "We can look at a certain map of the city, lay it over with modern GIS data, put the terrain in, and then notice, Oh, of course, they had to change the street patterns—the railroad ran through there. That makes sense. You can't always see change over time in a flat map by itself."

Many maps from the Hackerman collection are digitized, free from copyright restrictions and openly accessible for research on JScholarship, the university's digital repository.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged history, maps, george peabody library, baltimore city