By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart died at the ripe old age of 35, he had composed a staggering amount of work: 41 symphonies, 27 concert arias, 26 string quartets, 27 piano concertos, 21 stage and opera works, 17 piano sonatas, 15 masses, 12 violin concertos, and so on—more than 600 works, all told.

One piece he didn't finish, however, was the Requiem Mass in D minor, which was eventually finished by Franz Xaver Süssmayr, a young conductor and composer who worked briefly as a copyist for Mozart.

It's an ideal piece for the Hopkins Symphony Orchestra to play this weekend as part of its final concert at its recent temporary home venue, the Bunting-Meyerhoff Interfaith and Community Service Center. The Interfaith Center's warm, responsive acoustics make it an ideal regular home for the HSO's smaller concert orchestra, and the HSO has nimbly adapted its larger symphony orchestra to the intimate chapel.

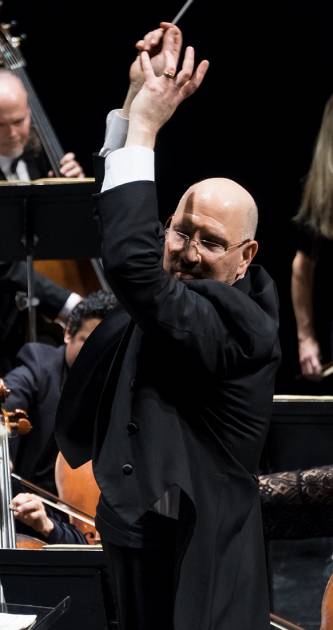

Image caption: Jed Gaylin

Image credit: Matt Crowne

"We had originally planned doing a concert version of La Boheme for this program, and that wouldn't have fit," Jed Gaylin, HSO music director, says with a laugh. "The beauty of the Mozart Requiem is that it calls for a relatively small wind section and a reasonably sized string section, plus the chorus and four soloists. We programmed this concert completely with the Interfaith Center in mind. There's just something about performing a requiem mass in a church."

There's also something about an orchestra performing a so-called unfinished work during the time when its usual home base remains unfinished. In the spring, the HSO will return to Shriver Hall following its welcome renovations. In the interim, the HSO, as artists do, has creatively adapted its repertoire to its temporary venues.

For this weekend's program—performances take place Saturday and Sunday—Gaylin complements Mozart's Requiem with Luciano Berio's Rendering, which is the Italian composer's completion of Franz Schubert's unfinished Symphony No. 10.

"I think this is a really fascinating pairing of two works that I'm very excited about it," Gaylin says. "And it wouldn't have come about if we weren't going to be in the Interfaith Center."

The Hub caught up with Gaylin to talk about what Mozart may have been up to with the Requiem and the role the conductor plays when working with uncompleted scores.

As a non-musician of a certain age, everything I thought I knew about Mozart's Requiem came from the film version of Peter Shaffer's Amadeus play, which I now know takes liberties with how things may have played out. What is the story behind this work?

The Mozart Requiem was commissioned by an unknown person who may or may not have been wanting to cop it as his own. We don't know too much about that, but it was commissioned—Mozart needed the money. But Mozart was a devout Catholic—and a libertine, and those two things are not immiscible. And I believe that the Tuba Mirum section of the Requiem is a fervent protestation to God, saying, "Who am I to stand before you when even the just are insecure?" This is Mozart's plea. At one point in the Recordare, he's asking, "Let me stay with the sheep," those who were saved, "and separate me from the goats."

I believe that this is a desperate plea on Mozart's part, despite his profligate lifestyle, to be saved on his deathbed. In an Old Testament way it challenges and confronts God, as though he's already meeting his maker and saying, you know, keep me upstairs. So I think he staked his salvation on this piece, and that he didn't complete it is of course harrowing. And I chose the Berio piece to complement Requiem specifically with the idea of two very different approaches to having a piece that is left incomplete completed.

Berio is one of those composers who I first got to know through his electronic works and experimental pieces for soloists, and when I finally heard some of his orchestral pieces, I was struck by how he's equally ambitious in his approach to larger ensemble works.

He's very ambitious, and I think he was an eclectic artist in a very organic way. He's a really accomplished musician and somebody who early on was exploring the collage elements of life in the 20th century. He's done other completions of unfinished works, and he's specific in this score to say that he considers this restorative rather than completing.

Having a piece that is about taking a score and rendering it ready for a performance by another composer is something that all musicians do. We take that blueprint and try to render it. Berio is doing it a specific way here and wrote that he sees it more as restoring an old Roman fresco. He's going to try to bring out the colors as he thinks they would be, but for the patchy part he's not adding his own bits to try to sound like Schubert. He leaves a kind of shimmery musical equivalent to scaffolding, so you know very clearly where Schubert leaves off.

And Berio always introduces that scaffolding with the sound of the celesta, which is very ethereal. It's a sound that was completely foreign to Schubert's sound universe and yet has the same kind of delicate quality that Schubert's music has. It's a very sensitive work of restoration.

The fresco comparison is a nice visual analogy for a composer's relationship to an unfinished work.

I thought it would be really fascinating to bring in a curator for our pre-concert talk to tie this all together. Harry Cooper, a curator and Head of Modern Art at the National Gallery, is going to talk about what it means to restore art works and the implications of doing such work without ladling too much of our own syrup on top of it.

As a conductor, how do you approach working with an orchestra when performing so-called unfinished pieces? Like you said, you don't want to put too much of your own syrup on top, but at the same time you're in some way interpreting an interpretation.

That's an interesting question because with both of these works another composer—Süssmayr in the case of the Mozart and Berio in the case of the Schubert—has done a lot of the work for you but some questions remain. Last night in rehearsal we get to the Benedictus in the Requiem, which is all 100 percent Süssmayr, and he has a nice balance of trying to honor what Mozart had done and complete it without egotistically saying here's my chance to make a name for myself. And in the Benedictus, Süssmayr—who was very talented and also died very young—there are all kinds of beautiful things, but it doesn't have the same kind of natural, organic quality that Mozart does.

So it is a challenge to conduct these works because we don't really know what Mozart would have come up with. Süssmayr followed some indications by Mozart to use some of the musical material in the opening in the final musical number, but that does give the Requiem a harrowing, raw quality at the end. It works effectively, but we'll never know what Mozart would have done.

Also, the Requiem is far more lacking in dynamics—such as indications to play softer or louder—than, for instance, Mozart's operas and symphonies from his later period in life, which means his early- to mid-30s. So we look at that and say, I think that we should go ahead and adjust things a little bit here and there where we think Mozart would have done that, given what we know from his other scores.

The HSO will be joined by the JHU Choral Society and Baltimore School for the Arts Chorus at this concert. How are the choirs sounding in the Interfaith Center?

They sound great. We've loved working with these choirs—the Hopkins Chorus has been a collaborator with the orchestra since 1996. Mark Hardy is the conductor of both of those groups, and he's a very dear friend and colleague. The School for the Arts students bring a lot of energy to the performance. We feel it's important to work with public schools and be able to highlight talent from the city. And we've got a smashing quartet of soloists for the program who blend together beautifully.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion