- Name

- Geoff Brown

- Geoffrey.Brown@jhuapl.edu

- Office phone

- 240-228-5618

- Name

- Michael Buckley

- Michael.Buckley@jhuapl.edu

- Office phone

- 240-228-7536

Lee Hobson and Ed Whitman flew to Florida in style three months ago, touching down in the Sunshine State in a Boeing C-17 loaded with priceless cargo: the Parker Solar Probe.

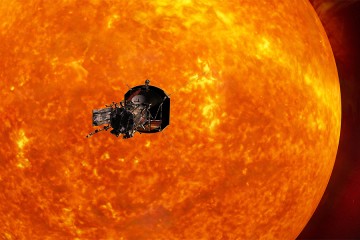

Hobson, director of photography for the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, is the video documentary lead for the APL-led mission to "touch" the sun. He and Whitman, APL's senior photographer, have spent the past four years painstakingly documenting the construction and testing of the probe, which is scheduled to launch in August. Flying through the sun's corona, or atmosphere, and facing heat and radiation like no spacecraft before it, the Parker Solar Probe will provide new data on solar activity and make critical contributions to scientists' ability to forecast major space-weather events that impact life on Earth.

Image caption: Lee Hobson (left) and Ed Whitman inside the clean room at Cape Canaveral

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

The Hub caught up with Hobson and Whitman to talk about their work, the mission, and what it's like to stand in the presence of the spacecraft that could change humanity's understanding of Earth's closest star.

How did you get involved with APL and documenting its projects?

Ed Whitman: As a kid, I was always fascinated with how things worked. There was nothing in my home that was safe from me and a screwdriver. I knew early on that I wanted to do photography, and I had my own company for many years, but when the opportunity at APL came up it just seemed like the right fit. I took the position and just loved it because, you know, I'm basically a frustrated engineer.

Lee Hobson: I joined in 1988 as a staff photographer and then moved into the video sector in 1996. On any given day I could be working in air defense or force projections, or national security analysis and research, or of course space exploration. That's what's really cool about APL—there's a lot of different things we work on.

Image caption: "[W]e're working next to the spacecraft that's going to fly within 4 million miles of the sun, and I get to walk around the launchpad. That's really cool," says Hobson.

Image credit: Ed Whitman / Applied Physics Laboratory

What's it like to document the Parker Solar Probe?

LH: The average day is about 10 hours here, but it's sometimes as long as 15 hours depending on what we're doing. Ed and I are unique in that when the day's operation is finished, we don't go home, we come back to the office to edit footage. So it can be a really long day.

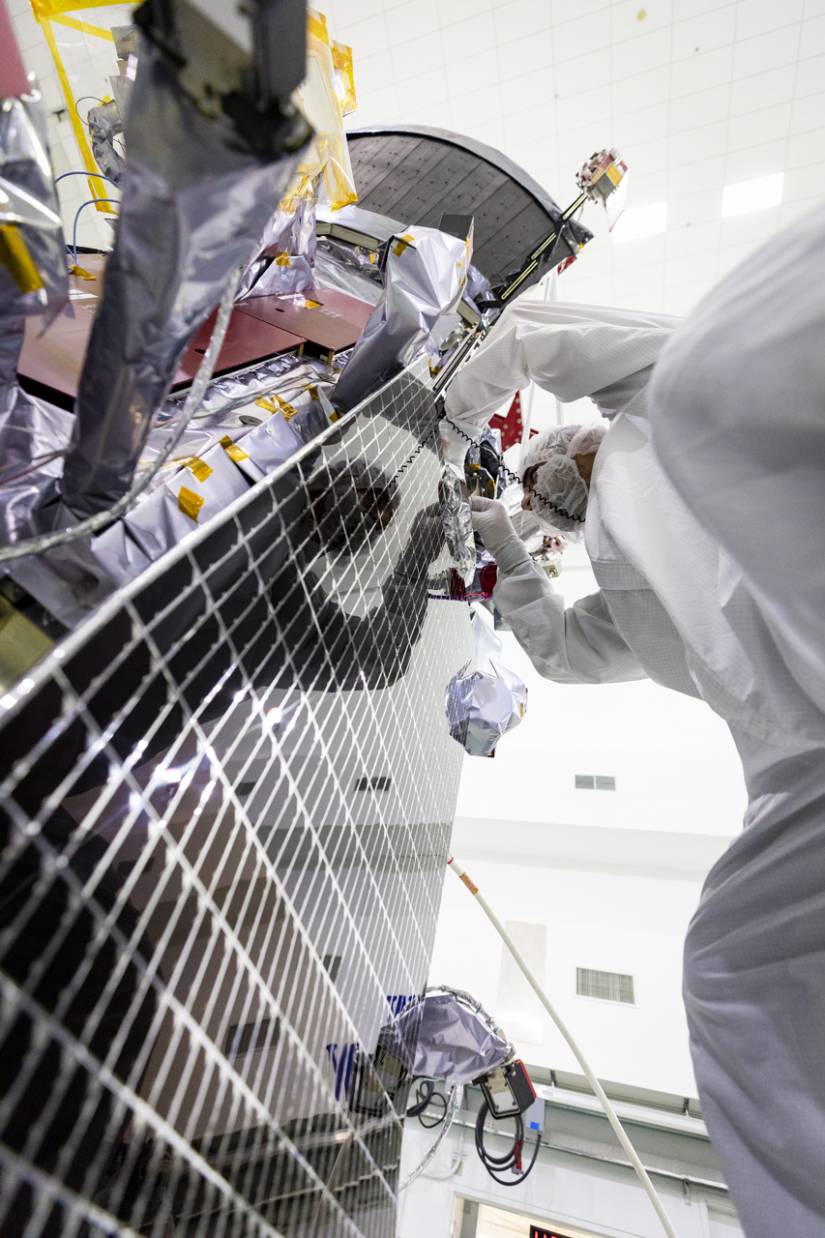

EW: We do press releases for the public, and those are more like the milestone events when significant things happen. But day to day, I'm working with the mechanical team, shooting everything that's being integrated into the spacecraft—every nut, every bolt, every process that takes place. And that's helpful because if the mechanical team gets a faulty software reading or a piece of hardware that's not functioning properly, they can go back through our photos and images and diagnose the problem.

Video credit: Lee Hobson / Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory

What's been your favorite experience documenting the Solar Probe?

LH: I've really enjoyed writing and editing the Solar 60 video series. I wanted to come up with a way of telling a story through the eyes of our different technicians and scientists and engineers. They get to be the reporters, and they have great camera presence, and I get to be the producer and script writer. So that's a lot of fun, getting to tell those stories. And, of course, the access that I have to the spacecraft. I mean, we're working next to the spacecraft that's going to fly within 4 million miles of the sun, and I get to walk around the launchpad. So that's really cool.

EW: For me, it's interesting to see the process of building something that's so highly engineered and thought out but is still a one-off that's never been built before. And I got to integrate my photography with the mechanical team for a test they needed to conduct: They had to lift the spacecraft way up in the sky and then drop down this magnetometer boom, and they had to do it really carefully so they could see how things were working. As it was coming down, I was walking around taking photos in 360 degrees, and I was shooting the photos to the lead engineer using my iPad. I mean, this $2 billion spacecraft is dangling from this lift in front of me and from my photos, the engineer can see the boom harness and determine the clearance and how it interacts with the spacecraft.

Image caption: Engineers created a bank of lasers to test the solar arrays that will power the spacecraft. "When we turned off the lights, magical things happened," says photographer Ed Whitman. "Reflections and a purple glow everywhere... Visually, it was really incredible."

Image credit: Ed Whitman / Applied Physics Laboratory

What's the most surprising thing about your work with the Solar Probe?

EW: The spacecraft is so light! It's only 1,500 pounds, and it's being launched in literally the biggest launch vehicle ever built, the Delta IV Heavy. It's a monster! It stands in front of you like a building. You feel so tiny and insignificant when you look at it, and the spacecraft—they call it a hood ornament—it's this tiny thing in this giant housing, but those are the things that are going to fall away during launch. It's just mind-boggling to me.

Image caption: "[The spacecraft is] being launched in literally the biggest launch vehicle ever built, the Delta IV Heavy. It's a monster! It stands in front of you like a building," says Whitman.

Image credit: Ed Whitman / Applied Physics Laboratory

How do you think you'll feel when the Parker Solar Probe finally launches?

EW: I'll feel probably sad and elated. Happy that I was part of something that's just so awesome, but sad in the sense that I don't want it to end because it's just so exciting and so interesting.

LH: I'm always really proud when we have a successful launch, and we've gotten that telemetry maybe 20 minutes after launch that means it survived and that the engineers built a really good spacecraft. But also I'll feel really proud when we start to get the data sent back. I mean, the Parker Solar Probe is going to rewrite the textbooks with new information about the sun and the corona, and I've touched it—the spacecraft that's going to fly around our sun and give scientists information that they never knew before. That's really exciting.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, nasa, outer space, parker solar probe