The following originally appeared as a news story from the Bloomberg School of Public Health.

When Tara Loyd, MPH '08, arrived at Hopkins in 2007, she had a plan. She was 30 years old and fresh from a position in Lesotho, a country in southern Africa, where she'd volunteered with Partners In Health and co-founded a safehouse and outreach program for children orphaned by HIV. Loyd came to Baltimore to earn her MPH at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health on a Reed Frost Scholarship. Then she'd return to Lesotho, where a job was already waiting for her.

Her plan did not include meeting James Keck, MD, MPH '08, at the most romantic place any two MPH students could meet: the Bloomberg School Activities Fair.

Loyd and Keck started dating over the next year. As convocation approached, they arrived at a crossroads: Loyd planned to move back to Lesotho, and Keck had one more year in the Preventive Medicine Residency Program, which included six months in Ecuador with the Pan American Health Organization.

Loyd had always chosen her work in public health over relationships. This time, the choice didn't seem as simple.

"I was at the precipice to take a martyrdom path," Loyd recalls, as she weighed what she saw as her two choices: take the job in Lesotho or stay in Baltimore with Keck. She'd always felt called to global public health work, but she also wanted a family.

One morning, Loyd's dad took her out to breakfast and asked her: Where did she see herself in 10 years, or 20, or 50? Which had the stronger pull: the idea of being a family or having a fulfilling global public health career? Were those mutually exclusive?

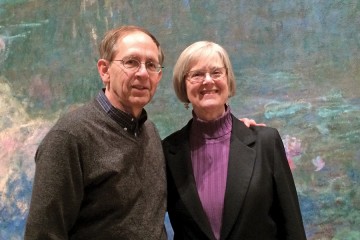

Image credit: Courtesy of Tara Loyd and James Keck

"People don't always know what their values are until they're faced with a situation where they might be compromised," Loyd says. And over that Shoney's breakfast with her dad, Loyd made the decision to stay in Baltimore with Keck. The details would sort themselves out.

The next step, an intimidating one, was to inform her would-be supervisor in Lesotho. Dreading the phone call to turn down the position, Loyd was prepared to defend her decision.

To her surprise, the director encouraged her to "follow love," Loyd recalls. "She said something along the lines of, 'you will always find a way to be of service to the poor and you will make your way back to a place like this.'" The director had spent most of her career working abroad, sacrificing family life for field research—a choice that came with some measure of regret. If Loyd had doubts about leaving Baltimore, the director explained, she should follow her gut. The work would always be there.

"She had hope that there could be a next generation of global health practitioners who managed families along the way," Loyd says.

Back in Baltimore with Keck, Loyd found a research coordinator day job at the Wilmer Eye Institute and worked nights and weekends waiting tables. When Keck finished his year of training, he unexpectedly landed a two-year dream job with the Epidemic Intelligence Service in Alaska.

Loyd and Keck married in 2010, packed up their lives, and relocated to Anchorage with the promise that their next move would be for a job opportunity for Loyd.

Two years later, Loyd got her chance to return to Africa. "She picked the spot literally the farthest geographically from Alaska—Malawi," Keck jokes. "So I put my jackets and cross-country skis in storage and joined her there in 2011."

In the rural district of Neno, Loyd worked as a project manager for Partners In Health and Keck was hired as the director of monitoring and evaluation. Within the year, they were on to the next step of their shared goals: starting a family.

Walking through the markets visibly pregnant, Loyd says, actually created inroads for her work. "[There was a] kindredness with other women," she remembers. "I would get gentle applause or smiles from the women selling fruits and vegetables, sometimes because they, too, were pregnant, but often I think because the sight of the expat project manager in the same humbling position as everyone else was quite equalizing."

Image caption: Loyd and Keck's son Zeke with his friends in Malawi

Image credit: Courtesy of Tara Loyd and James Keck

Loyd took care not to verbalize anything about her pregnancy with local staff because fetal and maternal mortality are so common in Malawi that it's considered risky to even mention pregnancy until the postpartum survival of both mother and child. Loyd struggled with whether to give birth in the rural district where they lived, alongside the women she worked with and cared for, or to return to the U.S. In Neno, women were faced with a bumpy two-hour drive on rough dirt roads when emergency obstetric care, like a cesarean section, was needed. The lifetime maternal mortality risk was a terrifying one in 36. In the U.S., this number is closer to one in 3,700.

Loyd opted to fly back to the U.S., where her long, grueling labor ended with a vacuum delivery. When she returned to Neno, infant in arms, she authorized the purchase of vacuum extractors for the district hospital.

Now, Loyd and Keck have two children and live near extended family in Lexington, Kentucky. Keck is an assistant professor of Family and Community Medicine at UK Healthcare and teaches global public health courses. Loyd works for PIVOT, a nonprofit that provides health care services in resource-poor areas. She shares a CEO position with a coworker at Harvard and works remotely with her team in Boston, overseeing ground operations for a project in Madagascar. She visits Boston every other month and spends six weeks every summer in Madagascar.

Image caption: “Being seen as a mother breaks down so many barriers I have as a white, English-speaking woman,” says Loyd.

Image credit: Courtesy of Tara Loyd and James Keck

Whenever possible, she brings her family along.

"The experience my children get by traveling to Madagascar is shaping their lives and our role as their parents," Loyd says. This, for Loyd and Keck, outweighs the potential risks of bringing children to an area with a plague outbreak, where health care is inadequate at best and other infectious diseases regularly kill thousands. They mitigate risk as much as possible, monitoring their children's water sources and making sure they have necessary medications on hand.

Besides, they reason, there are risks everywhere. In Madagascar, they know what many of those risks are and how to avoid them. And there, Loyd notes, her children get to experience a "freedom of childhood" she finds somewhat lacking in the U.S., and they get to reflect on their similarities and differences to people in another culture.

"Ultimately, we feel they are blessed by the amazing perspectives they have on their own privilege and the pride they take in being part of this work. One of my proudest moments as a mother happened recently when the PIVOT annual report arrived in the mail. My 5-year-old opened it and confidently started flipping through the pages, noting 'I know that doctor and that nurse, and look at the strip on that child's arm [a Mid-upper Arm Circumference strip to screen for acute malnutrition]—it's green so he is not going to be too hungry,'" says Loyd.

It also continues to forge inroads when she visits job sites with her kids in tow. "Being seen as a mother breaks down so many barriers I have as a white, English-speaking woman," she says.

Nearly 10 years after they met, Loyd and Keck have built a life on their shared goal of global public health service as a family.

"There's a whole generation of public health heroes that sacrificed their personal lives," says Loyd. "Now there's a group of us that are really trying to have global health careers as parents."

In sharing their values, Loyd and Keck have stayed committed to their work in public health, to their families, and to each other.

Tagged public health, alumni