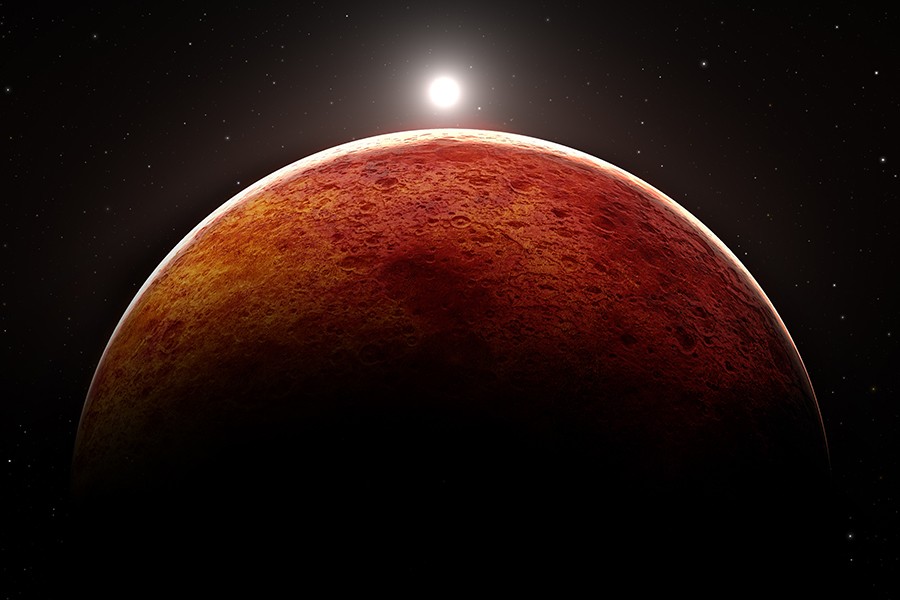

The prospect of liquid water on Mars and whether its presence signifies life on the planet has intrigued scientists and the general public for centuries, spawning all sorts of speculation and hypothesizing. Many wild notions have come and gone—seasonal vegetation, canals created by a civilization to carry water from the frozen poles—and the mystery continues.

So what do we know now, and what questions remain?

Lujendra Ojha, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, will deliver a slide talk on the most recent developments in the search for Martian water Friday afternoon in Mudd Hall, room 100. The event starts with a light lunch at noon. Ojha is scheduled to speak at 12:30 p.m. and will take questions at 1:30.

"I think people are most excited about the prospect of life," Ojha said.

There's certainly water on Mars, as about a third of the planet's surface is covered with ice. And there's water in the atmosphere. The trouble is that temperature and atmospheric pressure are not conducive for the appearance of liquid water, and certainly not pure water.

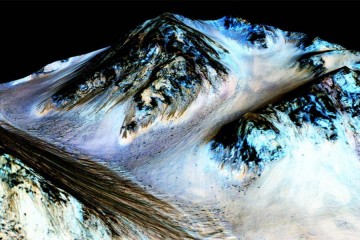

Ojha will talk about the most recent evidence of the presence of water in the seasonal dark lines on slopes known as "recurring slope lineae," or RSL, which could mark water trails. These were first spotted around 2010.

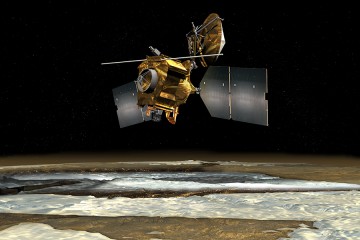

More recently, using images gathered by a powerful camera aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Ojha has been tracking seasonal changes in 10 landslides, or "slumps," in the landscape near a huge crater called the Juventae Chasma. These depressions—the deepest is about three feet—appear to be connected to the RSL and may be further evidence of water flow on the surface.

But how much water would have to be there to gouge the surface in that way? What is the source? How is it getting recharged? If it's not water then what else could it be? If it is water, then how salty would it have to be to remain in liquid form? Would it be toxic to life?

The more observations scientists make, Ojha said, the more questions they raise. Audience members can listen and ask their own questions at his lecture Friday.

Posted in Science+Technology, Voices+Opinion

Tagged earth and planetary sciences, outer space, mars