By examining data from NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, researchers from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory have found that gullies on modern Mars are most likely not being formed by flowing liquid water.

This new evidence will allow scientists to further narrow theories about the mechanisms behind the formation of gullies on Mars and help reveal more details about Mars' recent geologic processes.

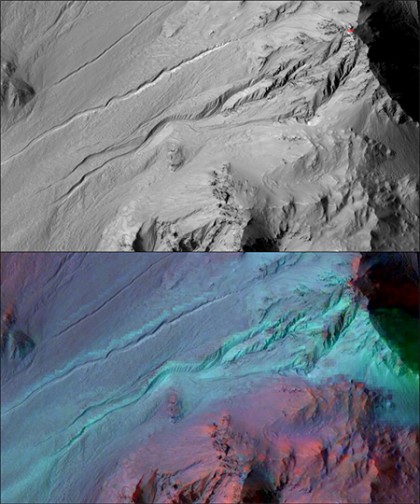

Image caption: The top image is a HiRISE image , and the bottom image is the same HiRISE image with a CRISM mineral map overlaid on top. No hydrated minerals are observed within the gullies in the CRISM image, indicating limited to no interaction of mafic material (light blue) with liquid water. These findings suggest that a different mechanism that does not involve liquid water may be responsible for carving these gullies on Mars.

Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona/JHUAPL

The findings, published online by the journal Geophysical Research Letters, showed no mineralogical evidence for abundant liquid water or its by-products, thus pointing to mechanisms—such as the freeze and thaw of carbon dioxide frost—other than the flow of water as being the major driver of recent gully evolution.

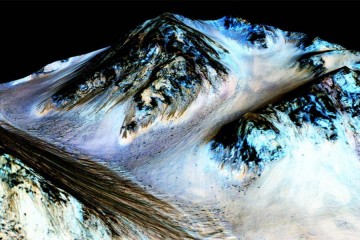

Previous observations by the team provided the strongest evidence yet that liquid water flows intermittently on present-day Mars. The new data doesn't contradict those findings, which pertain to another type of feature on Martian slopes, streaks called "recurring slope lineae," or RSL. Rather, the new information gives scientists further insight into how a different geologic feature of the Martian surface forms.

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, or MRO, collected high-resolution compositional data from more than 100 gully sites on Mars. Data collected by the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars , or CRISM—built and operated by APL—were correlated with images from the spacecraft's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE), as well as from the MRO Context Camera (CTX). The team took advantage of a new CRISM product, the Map-projected Targeted Reduced Data Records (MTRDR), which allowed them to more easily perform their analyses and then correlate the findings with HiRISE imagery.

"The HiRISE team and others had shown there was seasonal activity in gullies—primarily in the southern hemisphere—over the past couple of years, and carbon dioxide frost is the main mechanism they suspected of causing it. However, other researchers favored liquid water as the main mechanism," said Jorge Núñez of APL, the lead author of the paper. "What HiRISE and other imagers were not able to determine on their own was the composition of the material in gullies, because they are optical cameras. To bring another important piece in to help solve the puzzle, we used CRISM, an imaging spectrometer, to look at what kinds of minerals were present in the gullies and see if they could shed light on the main mechanism responsible."

Scientists have used the term "gully" for features on Mars that share three characteristics in their shape: an alcove at the top, a channel, and an apron of deposited material at the bottom. Gullies are common on the Martian surface, mostly occurring between 30 and 50 degrees latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres. On Earth, similar gullies are formed by flowing liquid water; however, under current conditions, liquid water is transient on the surface of Mars, and may occur only as small amounts of brine. The lack of sufficient water to carve gullies has resulted in a variety of theories for the gullies' creation, including different mechanisms involving evaporation of water and carbon dioxide frost.

"On Earth and on Mars, we know that the presence of phyllosilicates—clays—or other hydrated minerals indicates formation in liquid water," Núñez said. "In our study, we found no evidence for clays or other hydrated minerals in most of the gullies we studied, and when we did see them, they were erosional debris from ancient rocks, exposed and transported downslope, rather than altered in more recent flowing water. These gullies are carving into the terrain and exposing clays that likely formed billions of years ago when liquid water was more stable on the Martian surface."

Other researchers have created computer models that show how sublimation of seasonal carbon dioxide frost can create gullies similar to those observed by MRO, and how their shape can mimic the types of gullies that liquid water would create. Núñez said that this new research suggests those models may be correct.

"Our findings don't rule out the possibility that liquid water may contribute to the formation to some gully systems, since liquid water may be responsible for [recurring slope lineae, another feature on Martian slopes], which are completely distinct from gullies. But we did not find any mineralogical evidence of deposition or alteration where liquid water was the primary mechanism," Núñez said. "What we've found helps us get a better picture of how these interesting features on the surface of Mars can form and change, and that in turn gives us better insights into the recent geologic history of the planet."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, space exploration, nasa, mars