"Math, science popular until students realize they're hard," the headline says.

It reads like it came from the satirical online site The Onion, but this Wall Street Journal headline encapsulates a real problem in American education, says Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth alum Dan Zaharopol.

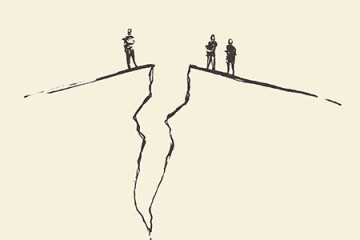

The prestige and high salaries associated with some STEM-related jobs may entice students to pursue degrees in STEM fields. Yet after they start the required college math courses, many realize there's a gap between the math they learned in high school and the highly advanced concepts they need to know in college. This can be a major obstacle for college success—especially for low-income students, Zaharopol says.

"A lot of students just don't realize how much math they're going to need for their college major," he says.

Zaharopol took CTY summer courses in astronomy, neuroscience, and computer programming, and he received a degree in mathematics from MIT in 2004. He visited Johns Hopkins last week to discuss how he is working to close this math gap with Bridge to Enter Advanced Mathematics, or BEAM, the program he founded in 2011 for young, underserved students.

In his talk, hosted by the Johns Hopkins University's Department of Mathematics, Zaharopol stressed the importance of giving STEM-bound students early access to college-level math.

College is a difficult transition for everyone, he says, but on top of the usual challenges, an underserved student will have had far fewer academic experiences that demanded college-level thinking. In many K-12 schools, educators are focused on proficiency—making sure all students reach a basic level of competence, he says.

"But in college, we're looking for mastery," he says. "We're looking for students who become doctors who are not going to make a mistake. We're looking for engineers who are going to build a bridge—and it would be nice if the bridge didn't fall down."

Image caption: Dan Zaharopol, CTY alum and founder of BEAM, a nonprofit that educates bright, underserved math students

Mastery comes from pushing oneself to strive for greater challenges and a deeper understanding; traditional school classes often provide the beginning, but not the end, of a STEM education. Nobody thinks Serena Williams or LeBron James got where they are because of their high school gym class, Zaharopol says. So how can students access advanced work in a relatively standardized system? The key is connecting them with programs, mentors, and practice outside of school that will help them build mastery before college.

BEAM partners with schools where a high percentage of students qualify for free and reduced meals. Its summer programs served 175 New York City sixth- and seventh-graders last year and will expand to Los Angeles next summer with help from a $1 million grant from the Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. The free program also offers academic mentoring and support to its more than 400 alumni, many of whom go on to receive scholarships to take CTY courses in high school.

Students are recruited for BEAM as sixth-graders based on an admissions test and teacher recommendations. Qualified students are admitted to its summer programs, which are similar to CTY's in that students spend about seven hours per day for three weeks on a college campus immersed in an area of study. At BEAM, that area is math, and students learn logical reasoning, number theory, math competition strategies, knot theory, infinity, and computer programming, among other subjects.

It's rigorous, but Zaharopol says students who are destined for math-heavy STEM careers rise to the challenge. BEAM alumni have been accepted to prestigious New York City high schools and are now pursuing STEM degrees at top colleges.

"The takeaway is that with the right resources and guidance, students can achieve at a high level and do advanced work," Zaharopol says.

Posted in Science+Technology, Politics+Society

Tagged education, center for talented youth, stem education, stem