Since President-elect Donald Trump's surprise election victory, the businessman's environmental platform and policy promises have drawn sharp criticism from scientists and public health experts.

Many fear that a Trump administration, with its skeptical stance on climate change and ambiguous conservation platform, could stall or undo progress made in recent years to stabilize the climate. Their concerns weren't eased Wednesday with Trump's nomination of Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt—who has written that the climate change debate is "far from settled"—to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.

The damage wrought by a dramatic shift in environmental policy, scientists say, could last well beyond the president-elect's term in office.

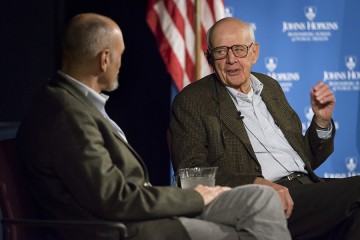

"I don't think the Trump administration is going to be very science-oriented," says James Yager, acting director of Johns Hopkins University's Center for a Livable Future.

For a closer look at how President-elect Trump's policies might affect the environment and public health, the Hub spoke to Yager and other policy experts from Johns Hopkins University's Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for a Livable Future, and Krieger School of Arts and Sciences.

During the campaign, Trump repeatedly pledged to support the fossil fuel industry—coal mining in particular. His transition website states that "rather than continuing the current path to undermine and block America's fossil fuel producers, the Trump Administration will encourage the production of these resources by opening onshore and offshore leasing on federal lands and waters."

The president-elect's promise to revive coal, if he follows through with it, could come at significant health and environmental costs. Coal-fire plants and surface mines destroy wildlife and emit pollutants such as sulfur dioxide, nitrates, metals, carcinogens, and carbon dioxide. As a result, Yager says, nearby residents are at increased risk of asthma, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

"The medical costs alone of treating that are going to be huge," Yager says. "The number of deaths that result from it is very large, and so the benefit of reducing this kind of pollution is decreased health care costs. If you want primary prevention, what do you do? You eliminate the source that's causing the adverse heath effects. In this case, it's burning fossil fuels."

Cindy Parker, an assistant scientist in JHU's Center for Global Health, agrees.

"Most greenhouse gases are also air pollutants, and so we can work on reducing them to help the climate, but we can also work on reducing them to help the health of residents," she says. "As we take away those protections, the health of residents will suffer, and right away—not in 100 years, and not on the other side of the world."

Also see

Trump has also said he plans to undo all of President Barack Obama's executive orders, including one that bypasses Congressional approval and effectively ratifies the Paris Agreement. Trump has pledged to "cancel" U.S. participation in the agreement, which goes into effect in 2020 and has been adopted by more than 100 nations.

Unveiled last year at the United Nations Climate Change Conference, the agreement aims to limit carbon emissions so that global temperatures do not exceed to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

Naveeda Khan, who attended the 2015 conference and directs graduate studies in the Department of Anthropology in JHU's Krieger School, says that limiting to a 2-degree increase doesn't go far enough.

"Really what is needed is a commitment to less than 1.5 degrees—the difference in half a degree is the small island nations," she says.

Adds Parker: "We know we have a window of opportunity for getting the climate stabilized at a level that will not be totally detrimental to the health and well-being of people and organisms on the planet. Having four years of climate setbacks really jeopardizes our ability to get the climate stabilized at a reasonable level."

Scientists say that despite threats to hard-won victories like the Paris Agreement, the environmental movement has gained momentum at the local level in the U.S.

"Cities have been doing a fair amount about climate change in the absence of federal legislation already, and so refocusing on cities to get things done is one strategy that probably has good promise," Parker says. "In many ways, it's easier to rally local communities around local issues than global climate change, which is often seen as taking place on the other side of the world and in a hundred years. Those are hard metrics for most people to relate to."

Framing the health of the environment as a human health issue could also strengthen the movement, Parker adds.

"Regardless of whether you believe in climate change or not, you're still going to suffer the impact," she says. "Like gravity—it still happens whether you believe in it or not."