In the opening days of 2016, President Barack Obama attempted to steer the national conversation to guns. The violence witnessed in the United States the previous year demanded action.

By some assessments, 2015 was the year of the mass shooting. During a prayer service at a Charleston, South Carolina, church, a lone gunman killed nine people, including the senior pastor. On a community college campus in Roseburg, Oregon, a student fatally shot nine people and wounded seven. In San Bernardino, California, a married couple opened fire on a holiday party, leaving 14 people dead and 22 wounded.

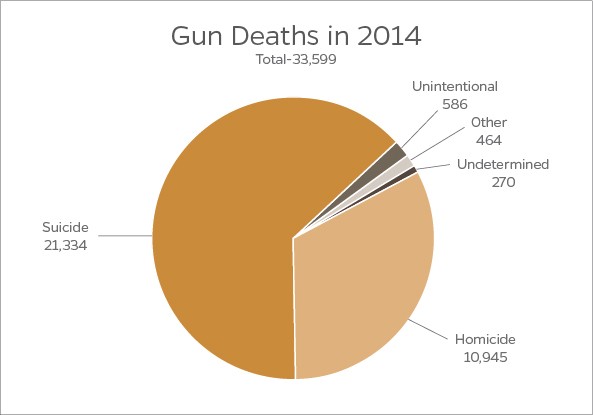

While there is no formal definition of "mass shooting," the crowd-funded website Mass Shooting Tracker defines a mass shooting as one that kills or injures four or more people. By that definition, there were 372 mass shootings in the U.S. in 2015 that killed 475 people and wounded 1,870. When you take into account other gun-related deaths, more than 33,000 people in the U.S. lost their lives due to a firearm last year.

President Obama stressed a sense of urgency as he unveiled, on Jan. 5, a "Common-Sense Gun Safety Reform" that would require those in the business of selling firearms to be licensed, expand background checks to sales by private sellers, improve mental health outreach aimed at preventing gun rampages and suicides, and boost gun-safety technology.

Yet, despite Obama's efforts, sweeping gun reform remains elusive, and the violence continues. On June 12, 2016, a 29-year-old security guard killed 49 people and wounded 53 others in a terrorist attack/hate crime inside a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. Days after the event—the deadliest mass shooting by a single gunmen in the nation's history—the American Medical Association adopted a policy calling U.S. gun violence a public health crisis.

Over the past decade in America, more than 100,000 people have been killed by a firearm, and millions more have been the victims of assaults, robberies, and other crimes involving a gun. No other nation has had more mass shootings in the past 15 years than the U.S. There are also more guns per capita in the U.S. than in any other nation—88.8 guns per 100 residents, according to the Small Arms Survey, a Geneva-based research project.

According to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, U.S. gun-makers produced nearly nine million guns in 2014, and there are more than 230 million guns currently in circulation. Nearly 22 percent of Americans own guns—and 25 percent of those gun owners own five or more firearms.

For more than 20 years, the Center for Gun Policy and Research at Johns Hopkins University's Bloomberg School of Public Health has been dedicated to reducing gun-related injuries and deaths through the application of research methods and public health principles. Daniel Webster, who directs the center, says the gun issue is neither straightforward nor easily approached.

Why is changing gun policy in the U.S. so difficult?

Webster boils it down to two issues: the structure of our government and the effectiveness of the gun lobby. He points to the Republican-controlled Senate and the need, practically speaking, for 60 or more votes to pass legislation.

"There's no motivation for senators in rural states to vote 'yes' on gun reform, as there is no political benefit and it would likely come back and haunt them next election period," Webster says. "In this political climate, it's very, very hard to do something nationally."

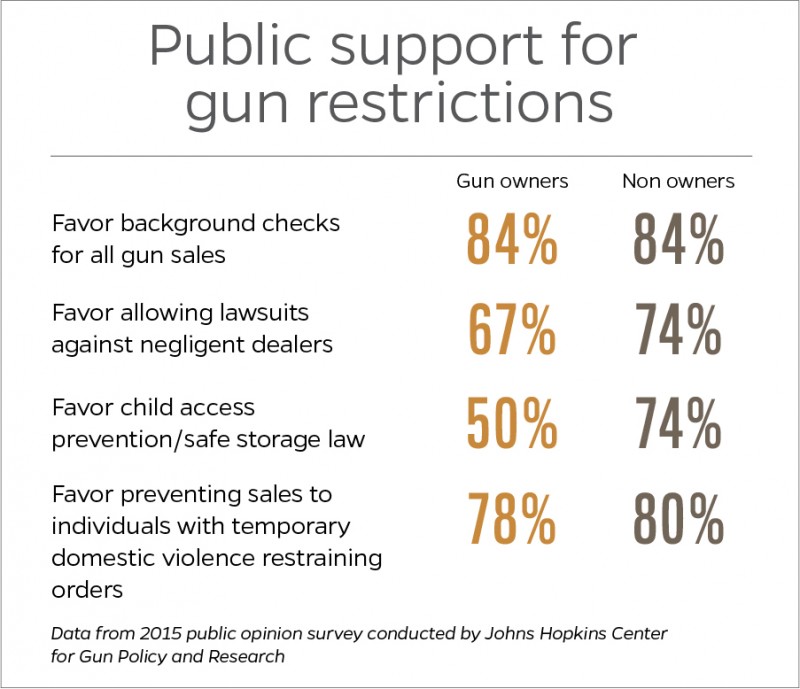

He adds that the National Rifle Association of America is incredibly effective, with a lot of help from media. When the Hopkins center conducts surveys on specific gun policies, such as expanded background checks and restrictions on individuals with a restraining order or multiple drunk driving offenses, 70 percent or more of gun owners and a similar percent of Republicans support changes.

"There's not much disagreement on who shouldn't have a gun in these cases," Webster says. "But the gun lobby changes the discussion and portrays any specific legislation as 'the government wants to change our way of life, take away our guns.' They make it a tribal thing. They are masterful at controlling the discussion and making it very difficult to come to a consensus. They fuel distrust of government."

What can we learn from states with more restrictive gun policies?

In states such as Connecticut and California that have enacted stricter gun policies—more restrictions, better regulation of gun sales, harsher penalties—Bloomberg School data shows a 40 percent reduction in suicides and homicides, and also a decrease in members of law enforcement shot in the line of duty.

The popular counter-argument, Webster says, is that criminals don't obey gun laws and stricter gun policies only make it "inconvenient" for law-abiding citizens. Webster says that argument is flawed and not so black and white.

"It's not a case of you're either a hardened criminal and evil to the core, or pure and always good," he says. "The reality is many of us fall in this huge grey area. Our circumstances change. And people don't want to go to jail. These deterrents work. There is a meaningful number of people who might do harm with a gun, but the changes in cost in terms of risk for illegal gun possession stops them."

Nevada is looking into extending background checks. Similar legislation is being looked at in Maine and Arizona.

"These efforts are very active," Webster says, "and incredibly popular, but will they pass?"

How big of a factor is mental health in gun violence?

Some boil down the gun problem to mass shootings, but those only account for less than 2 percent of annual gun deaths. More than 60 percent of Americans who die from guns die by suicide.

There's also a belief that mass shooters are all crazy, but Webster says many don't have a diagnosed mental illness. One study found that only 4 to 5 percent of gun violence involves a serious mental illness.

"Some would make you think that if we put something in the water to cure all mental illness, gun violence would all but disappear. That is not the case," he says. "It would drop maybe 4 percent, and we don't have such a miracle cure."

Do we have a broken system in terms of mental health? Perhaps, Webster says, and certainly a reasonable case can be made that better mental health care could reduce the number of suicides.

Can we restrict access to certain types of guns, like assault weapons?

"Assault weapons" is a broad and flawed term.

Automatic weapons—those that fire continuously when the trigger is held down—are effectively banned in the U.S. A 10-year federal ban on certain semiautomatic assault weapons expired in 2004, and subsequent efforts to renew it or enact a similar ban in its place have failed.

The guns used in Orlando and San Bernardino—as well as the December 2012 mass shooting at a Newtown, Connecticut, elementary school—were semiautomatic weapons, which law enforcement sometimes refers to as assault rifles or assault weapons.

In short, some assault weapons are banned; others are not. But a ban on semiautomatic weapons, or weapons with detachable magazines, is controversial because not all guns that fit those descriptions are "assault weapons."

"Because these guns are really just ordinary rifles, it is hard for legislators to effectively regulate them without banning half the handguns in the country (those that are semiautomatic and/or have detachable magazines) and many hunting rifles as well," writes UCLA law professor Adam Winkler in a December 2015 Los Angeles Times op-ed.

Handguns—not assault rifles—remain the biggest problem, Webster notes, and overwhelmingly the majority of violent acts involve the use of a handgun.

"Concealability is really important, and it's the weapon of choice," he says of handguns. "Which is not to say we shouldn't look at assault weapons or weapons with magazines. But the issue is that the hunting industry, which is in decline, has tried to boost sales by marketing more exotic weapons. So taking away someone's assault weapon amounts to taking away his hunting weapon."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged gun control, daniel webster, election 2016