It's a good, virtuous life: In the morning, Marty Makary performs painstaking, delicate procedures on the pancreas, sometimes saving patients with the grimmest of prognoses. What's more, his surgical innovations have been key to restoring the lives of pancreatitis sufferers who, wracked by debilitating pain, previously had little hope of returning to normal. During the afternoon and evening, Makary, an associate professor of surgery at the School of Medicine, teaches those advanced techniques. On many days, his expertise and plain talk about medical matters pop up on CNN, where he plays a regular correspondent's role. And he was on a short list of candidates for U.S. Surgeon General in 2009. That's a serious resume for a young doctor, one who still has energy for weekend rounds of golf and regular trips to the Middle East.

Yet for all of those days well spent, Makary, 41, is far from satisfied. Dating back to his time at Harvard Medical School, something's been eating at his craw, gnawing at the core of what he does and who he is. Back then, the mistakes, oversights, and slights he saw in hospitals led him to leave med school. Doctors unqualified to perform operations did so anyway. Hospitals ignored their harrowing rates of infection. Patients often received care not because they needed it but because it was what their specialists were trained to give them. Too often, they had "care" shoved down their throats. "There were too many examples of, 'When you're a hammer, everything's a nail,'" Makary says. "I had to get out."

He dropped out to study public health, but would eventually return to med school to take his place among the oath takers, determined not only to do good but to do better. "When I first landed at a hospital, the other residents and I would talk about some shocking stuff—errors in surgery, dangerous glitches in basic care—over dinner or drinks," he recalls. "During residency, you see just how messed up things are. The problem is, it's very difficult to speak up about it all."

As years went by, things didn't change enough to calm him. So, two years ago, Makary decided to pipe up. After receiving and rejecting the usual tips on possible medical book subjects from publishing agents (such as the best vitamins for health), he decided instead "to write what was in my heart." What he found there was bile for a system that often puts itself forth as a charity but acts with the cruel calculation of a business. The result is the often pointed but ultimately hopeful Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won't Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care, published by Bloomsbury in September.

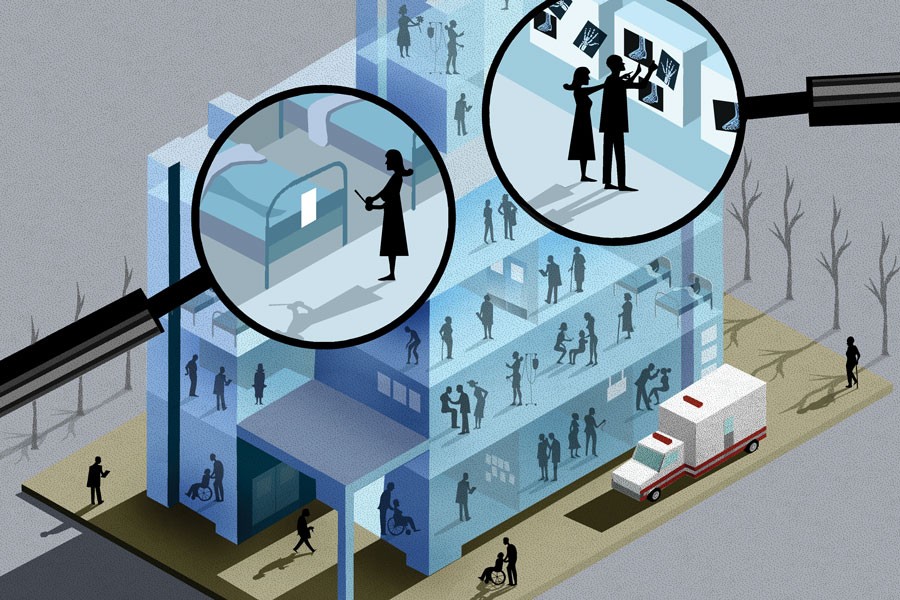

The book emerges at a time when the United States is facing questions about how to run a health system. "People are increasingly frustrated by the entire health care system," says Makary, a slight man with a deliberate and direct way of talking. "The culture of medicine, the way we do what we do, is the giant elephant in the room. It should be transparent, yet it isn't." Putting that culture under the microscope motivated him further, he says. "I thought it was the right time to change the health care debate."

Everyone has a hospital horror story, he says—everything from a relative who was given a dangerous prescription to a friend of a friend whose operation was performed on the wrong side of the body. "I'm hoping that people inside and outside the industry are starting to see they need to deal with this," Makary says. "When people saw that bank fees were out of control, many put their money into [lower-fee] credit unions. We need that kind of activism in medicine."

Though his book is far from autobiographical, Makary uses examples from his own medical career to present the inadequacies of health care. He relates, with regret and fine writerly detail, the tale about a night when he, as an exhausted resident, almost lost a patient on a ventilator because of a mistake he made. By writing about such instances, he hopes to inspire more doctors, nurses, and hospital administrators to bare their souls. "I'm trying to break down the closed-door culture of medicine," he says. "We keep our shortcomings to ourselves and we shouldn't. It's obviously stressful when patients suffer from a mistake, but it can be devastating for caregivers as well. If we can't talk about these mistakes, how can we change things, make them better?"

The idea that medicine—long viewed, perhaps wrongly, as an implacable, charitable source for good as well as a fount of continuous innovation—can be drastically improved by changing its culture is a relatively new one. Though concepts such as "accountability" and "transparency" have been trotted out from time to time, Makary believes that medicine is still a closed shop.

In Unaccountable, he specifically targets hospitals, arguing that they need to gather, analyze, and publish information vital to prospective patients. They should keep precise tabs on patients' surgical outcomes, the rate of hospital-borne infections, and other measures, and then put the statistics out where the public can see them (including on the Internet). Doing that would encourage hospitals to hold themselves to higher standards. They would be forced to rehabilitate, train, or weed out physicians and other professionals who need to do better, Makary says, and the practice of medicine would be greatly improved.

By focusing only on best practices, hospitals would also reduce the cost of care. Other improvements, such as placing video cameras in operating rooms and intensive care units, could catch bad surgeons and the potentially harmful habits of staff early on, before people are hurt, he adds.

Alas, hospitals too often do the opposite, he says, preferring to promote more costly offerings, such as robotic surgery, that offer no benefit to patients beyond that of more traditional surgical techniques. Doctors often receive what Makary fearlessly calls "kickbacks" to use certain machines or prescribe some drugs. None of this redounds to the patient's benefit or to the faith people have in the medical industry.

Meanwhile, hospitals see little gain in presenting statistics about their performance, Makary says—another impediment to better treatment. "Their thinking is, 'What if we have a bad year?' They'd rather keep the steady stream of money coming in. They know that people view them as a beneficent entity, almost a charity. But if they're going to behave like a business, such as by hiring aggressive collection agencies to go after patients, they need to truly act like a good business acts."

Unfortunately, too many medical centers wait till tragedy strikes before making changes, he adds. "The one thing that moves hospitals the fastest is patient deaths and botched surgeries that have been made public," Makary says. "After public relations disasters happen, you're much more likely to see cameras in operating rooms," along with other accountability measures.

Makary is careful to note that the vast majority of medical people are qualified and dedicated, and regularly do fine work. But his frustration is palpable. He came to write Unaccountable after years of dedicating half of his professional practice (his afternoons and nights) to research into patient safety. (These days, he is also an associate professor of health policy and management at the Bloomberg School of Public Health.) While many hospitals highlight glitzy new cancer centers, Makary believes they should emphasize safety at least as assiduously. "Advances in patient safety will save more lives than chemotherapy this year," he says.

Not long after coming to Johns Hopkins a decade ago, Makary created an operating room checklist designed to eliminate simple mistakes and to improve patient outcomes. He published the lowered postoperative infection rates that accompanied the use of the list, which was also highlighted in The Checklist Manifesto, a 2009 best-seller penned by Atul Gawande, a surgeon at Harvard and a writer for the New Yorker, as an example of how simple measures—washing hands, regularly sterilizing IV lines, communicating clearly, the checking off of duties by nurses—can go a long way toward making patients healthier. The surgical checklist was used as a model by the World Health Organization for its own checklist, which is now regularly posted on operating room walls around the world.

Along with the intensive care unit-centered work of Peter Pronovost, a professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at the School of Medicine, Makary has adapted widely used questionnaires that hospital staffs answer to determine how safe their practices are. The duo's research into making hospitals safer has saved uncounted lives—and reinforced Johns Hopkins Hospital's organized efforts to improve patient care.

Because of his groundbreaking research into patient safety, other physicians say he's the right one to blow the whistle on the medical profession. "He's been a dedicated observer of health care at several institutions and has published very strong research," says Michael Johns, a chancellor at Emory University, in Atlanta, and the former dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Johns, who got a sneak peek of the book, pre-publication, offers one caution: "He does a really nice job of grabbing readers' attention with his stories. But the book needs to be read in the right sense, and that is that there's room for improvement. You don't want people to read it and be afraid of seeking out care."

Makary's strong use of anecdotes to open chapters makes for compelling narratives. There's the neglect and abysmal living conditions suffered by wounded soldiers at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. A butchering surgeon that residents dubbed "HODAD"—shorthand for "Hands of Death and Destruction." An elderly patient who declined a biopsy but was given one anyway—with horrible results. Perhaps those thumbnail sketches are why 60 Minutes, Reader's Digest, Dan Rather Reports, and other shows and publications are lining up to interview Makary or excerpt his book. An independent film company is making a documentary about health care based on it. Bloomsbury, his publisher—the same outfit that released the Harry Potter books—has made Unaccountable its top priority for 2012.

For all the brewing hubbub, Makary insists he's not so much a single-minded activist as a messenger. "I didn't create this movement," he says. "We're at a turning point in American medicine now. There is a new generation of physicians that believes medicine should be transparent, that is tired of the old b.s., and wants to change things." But the old guard isn't far behind—which gives Makary even more hope. The Institute of Medicine, a vaunted research entity that often investigates best practices, and the American Board of Internal Medicine are starting to take accountability seriously. Even the doctor-protective American Medical Association has taken notice. "Doctors are monitoring exactly what they do. They're researching and questioning it," he says. "It's unprecedented."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged patient safety, surgery, malpractice, health care