For many people, showing an ID isn't anything to think twice about. But for those who lack official identification, there can be fundamental blocks to just about any step forward in life, such as securing a job or signing a lease.

In Baltimore, this problem is especially prevalent in the ex-offender population. After incarceration, many have lost access to their records and face an array of challenges—with technology, bureaucracy, or transportation—in order to retrieve them.

At the Living Classrooms Foundation, a Baltimore-based nonprofit, this issue comes up time and again—as an enrollment barrier for some of its outreach programs, and as an obstacle to connecting its visitors to other support structures in the city.

"What we've seen for a lot of people is a breakdown in communication," says Raquel Lilly, a manager at Living Classrooms. "A lot of them are extremely disconnected from their vital records and don't know how to navigate the system."

To address the issue, the nonprofit offers a weekly "Identity Clinic" service along with SOURCE, Johns Hopkins University's community engagement and service-learning center in East Baltimore.

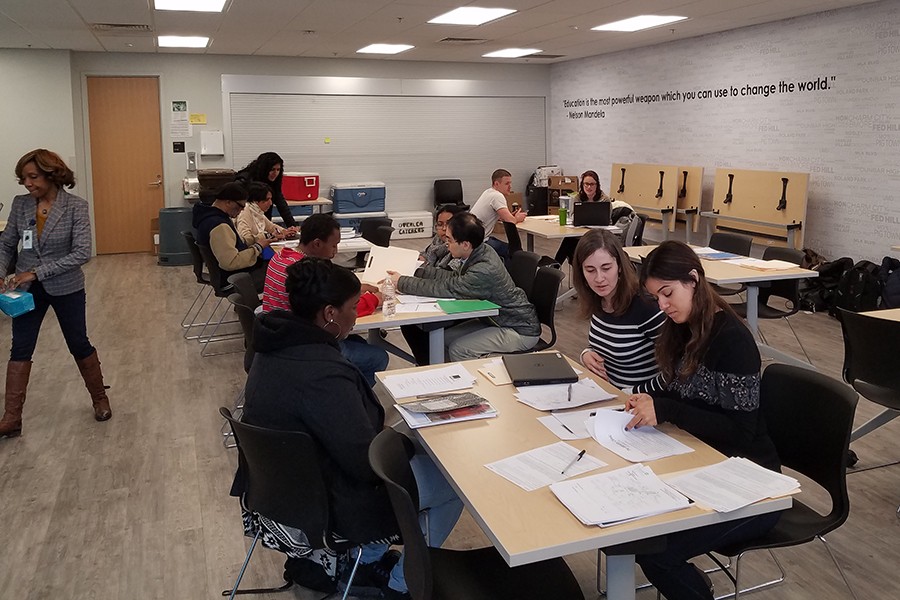

For two hours each Friday, Johns Hopkins grad students recruited and trained by SOURCE act as a concierge for visitors who need help tracking down or applying for various forms of official identification, such as birth certificates, social security cards, or state ID cards.

The program, bolstered by a $20,000 grant last spring from the Johns Hopkins Idea Lab, began operating this month at Living Classroom's UA House at 1100 East Fayette St.

Though the clinic remains focused on ex-offenders who are trying to get back on their feet, its volunteers have encountered a variety of scenarios. In its first two weeks, for example, the clinic helped a homeless man use hospital records and a letter from his shelter to start applying for a birth certificate. Another case involved an orphaned minor who needed to establish his identity so he could be legally adopted.

Lilly says the clinic also helped a married mother who wanted to take adult education courses, but after being incarcerated at a young age, she had lost track of her ID forms and needed to re-start the process.

"Each case is quite complicated, and you really see how people can get stuck in the system," says Poonam Daryani, who helps lead the Identity Clinic along with Joseph Shen, a fellow graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

As SOURCE Service Scholars this year, both Daryani and Shen are taking leadership roles with the Hopkins program, which organizes community service opportunities for JHU's schools of Public Health, Nursing, and Medicine. The two scholars helped Living Classrooms and SOURCE establish the Identity Clinic by creating protocols, recruiting and training volunteers, and providing oversight during the clinic's Friday hours.

Shen says he'd already seen the problem of missing identification come into play in his previous work with the SOURCE HIV Counseling and Testing Program, creating a barrier for patients trying to get medical insurance.

One of the mind-bending complications of the identification process is that from the outset, it requires proof of identity.

"In order to get an ID, you have to have ID—it's a bureaucracy and there's a lot of steps," says Shane Bryan, assistant director at SOURCE.

It can get particularly convoluted, he says, with ex-offenders who sometimes can't produce necessary documents such as utility bills or leases to prove their residence. And for this population, the risks are especially high for losing access to resources that can help them reintegrate into society.

"A lot of folks who don't have access to ID have higher rates of recidivism," Bryan says.

Volunteers at the Identity Clinic are trained to work through the red tape. At the Friday clinic, they're ready with laptops and guidelines. But they're also continuing to learn as they go along.

"It's very much trial by error," Daryani says.

Shen adds that beyond identification, the clinic is helping clients with other even more fundamental needs, like finding shelter or medical services.

Lilly, the Living Classrooms manager, says there's hope the Identity Clinic can grow beyond its initial grant to become a broader, permanent program serving Baltimore City.

"This is needed," she says.

Posted in Student Life, Community

Tagged community, idea lab, source, living classrooms