Last summer, Daniel Contaldo ('16) traveled around land once controlled by the Mafia in his native Italy. Funded by a Provost's Undergraduate Research Award from Johns Hopkins University, he filmed the activities of volunteer-run farm cooperatives that have sprung up on those sites since the Italian government seized the land a few decades ago.

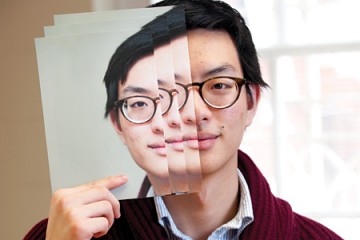

Image caption: Sarah Hewes

"It occurred to me to provide audiovisual documentation of this reality that many people in U.S. don't know about, and many people in Italy don't even know," says Contaldo, who is majoring in International Studies and Film and Media Studies at JHU.

PURA, a research support program for undergrads, provided Contaldo with funds for his travel and filming equipment as he interviewed the high-school-age volunteers at the farm camps, along with victims of past Mafia crimes. Faculty support was also available for Contaldo once he was back in Baltimore, editing down his hours of footage.

The end result is a 26-minute documentary, Taste of Justice, which Contaldo is now submitting to film festivals across the world.

His is one of about 45 research projects the PURA program helped produce this year. Others include an investigation of 3D-printing of blood vessels by Sarah Hewes ('15); an ethnographic exploration of how Korean youth culture relates to the West; and a study of the impact of oxygen deprivation on cancer metastasis. (The full list of projects and participants is available online.)

This cycle of PURA research started during the 2013-14 academic year. Undergraduates can apply for a fall or spring session, opting either for academic credit or for a $2,500 fellowship award, which can cover costs like living expenses, research supplies, or travel.

Typically, the research culminates in late April of the following academic year, when students display posters of their work and receive certificates through a recognition ceremony. That didn't happen this year—the ceremony was scheduled for April 28, the day the university closed in the wake of widespread unrest across Baltimore.

"We were forced to cancel the entire event," says Tracy Smith, research programs manager Office of the Provost, which runs PURA. Organizers decided that rescheduling was impossible given the hectic end-of-year schedule for students.

Smith says students have been dropping by the provost's office to collect their certificates; they'll also be invited to the next PURA ceremony, in April 2016.

It's the first time in PURA's 22-year history that students haven't had the opportunity to present their research. But the presentations aren't the be-all and end-all for the projects. Research results unfold in many forms, from published journal articles to music performances and short films like Contaldo's.

"We try to have it as diverse as possible," Smith says of the range of research. The majority of projects steer toward science and medicine, which more naturally "lends itself to research," she says, but the program is increasingly expanding to arts and humanities.

That includes research out of JHU's Peabody Institute—this PURA cycle included a project from Peabody student Andrew Landau ('16), who merged his intersecting interests in music and neuroscience. Landau has seen his love of music increase through his Peabody classes, but he started wondering exactly why that is, on a scientific level. His theory was that increased familiarity with composers and music history can tangibly affect enjoyment of the music itself.

"Just having that background knowledge of what Bach did and who he was, I get a stronger reaction when I hear Bach," says Landau, who is majoring in Saxophone Performance and Recording Arts and Sciences.

Through PURA, Landau conducted a study to test his theory. He played participants 30-second excerpts of classical compositions by three prestigious composers (Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven), along with three of their lesser-known contemporaries.

One group of study participants saw the correct names of composers flash on a screen as they heard the music; the others saw composer names that were deliberately mismatched with the music. And, as Landau predicted, name recognition counts. It turned out when "participants saw a famous name, they rated [the music] higher," he says, regardless of whether they weren't really hearing Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven.

A critical aspect of PURA is working with a faculty mentor. Landau worked with Charles Limb, formerly of the School of Medicine, a cochlear implant surgeon who studies artistic creativity, improvisation, and related neurological processes. Limb has since moved to University of California, San Diego, but continues to work with Landau on the project. They hope to publish their findings in a research journal.

Posted in Student Life

Tagged undergraduate research, pura