Historian Martha S. Jones has won accolades for her wide-ranging examinations of the lives of African American women and how they've fought for and won a distinctive place in the country's history. For her latest work, she set out to discover the intricacies of a very specific past: her own.

"I am among those writers who are conjuring an important and, I think, mighty tradition among Black writers —the writing of self," says Jones, whose The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir (Basic Books, March 2025) explores the essence of racial identity in this country by digging deep into her own ancestry.

Following in the writerly steps of poet Phillis Wheatley and Maryland-born abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass, Jones has created a deeply personal narrative that will resonate with anyone who has ever searched for details to their identity in the hues of their own skin, "a record of who we are," she says.

Such a record is often elusive for the American descendants of enslaved people. "We know too little about the Black past in the United States and are forever hamstrung, to a degree, in the way in which our stories are not recorded and not valued by the people that created these archives," says Jones, a Johns Hopkins professor of history and faculty member at the university's SNF Agora Institute.

She sought clarity for her own family and to answer a question posed by a fellow college student nearly 50 years ago: "Who do you think you are?" That student had observed Jones' light skin and straight hair and demanded to know how that fit into the politics and realities being discussed in their Black studies classes. "Obviously, it preoccupied me for a very long time, until this book," she says.

The definition of Black identity has changed in the past five decades. Jones describes herself as a "child of the one-drop rule," where any African ancestry designated one as Black, and "terms like 'multiracial' and 'mixed race' didn't exist," Jones says. "I am, with this book, really fully looking to inhabit a different kind of moment in the history of Blackness and of race, the history of generations."

Unlike many African Americans looking into their past, Jones started her research with a solid group of written records, including an interview of her late grandmother about the Civil Rights era and details about her grandfather, David Dallas Jones, the longtime president of Bennett College, a historically Black institution for women in North Carolina.

She had thought that material would be the basis of her book, "but when I started to look at those interviews, it became clear that they are carefully crafted stories for public consumption. Moreover, they were ridden with inaccuracies. One interview, for instance, got her grand?mother's name wrong; another text described her fair-skinned grandfather as a white businessman because his appearance and status seemed to suggest that.

"They don't always jibe with what I think I know, or with each other. It's a puzzle in and of itself, too many holes and too many gaps," she says.

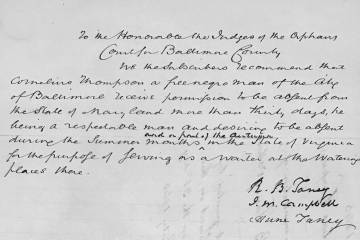

To fill those holes, Jones "put on my good old historian cap," poring over census records, death and birth certificates, and slaveholders' records. The Trouble of Color follows Jones as she traces her family from the South to her native New York state. At the heart of her quest are details of the life of Nancy Bell Graves, her great-great-grandmother, born in 1808 in Danville, Kentucky. The author was reminded how deeply uncomfortable questions of race remain in this country when she asked a local librarian about the Bells, the family that had enslaved Nancy.

"Now be careful," the woman told Jones. "What you're saying implicates one of Danville's most important families. She didn't have to use a lot of words for me to understand what the stakes were and how unsettling it would be for me to ask more questions," Jones says.

Rather than deter Jones, the librarian's reticence was "the most helpful thing because it told me there really was a story there, even if I didn't know the details. These are the people who remind us that there is power in our stories, when we try to tell them. In a funny way, she did me a favor. I'm a believer in being insistent with archives and not taking no for an answer, at least not the first time."

The Trouble of Color is a stark portrait of the still-unhealed wounds of America's relationship with its past. Jones wrote part of the book in Germany, a country that "has a much more pronounced sense of what is appropriate and not appropriate in sites that were one-time scenes of crimes against humanity."

That's a different reality in the United States, where weddings are held on the manicured grounds of former slave plantations like Kentucky's Oxmoor Farm, a site Jones traveled to while researching a possible family connection. Touring Oxmoor—now an event center and site of bourbon tastings—proved to be an uneasy experience for the professor.

Also see

There, in a place where her ancestors may have been held in bondage, "I was not a removed researcher. I was not a curious tourist. Instead, I was looking for signs of my own family amid its potent blend of restored opulence and repressed terror," Jones says. "I still think that, collectively, as Americans, we haven't wholly incorporated into ourselves what it means to vacation, entertain, and party in these places."

As uncomfortable as these truths can be, she was determined to "bring people along with me on the journey, and the discovery, and all the things I can't discover. I hope that by placing myself in that dilemma, folks will recognize their own."

And Jones hopes that her book "encourages people looking for signs. Out of small bits, little scraps of the past, we can dissect how to tell stories. I hope that it honors and contributes to the ways that we continue to honor our ancestors, who they are and how they shape us. We were not born out of whole cloth as 21st-century beings. We come out of history, and knowing these stories helps us see who we are."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged history, race, memoir, martha jones