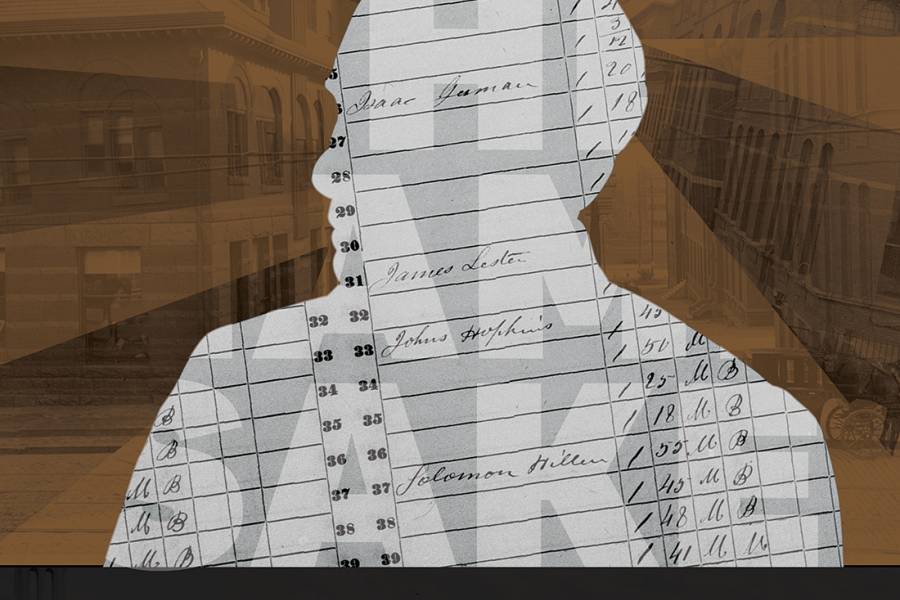

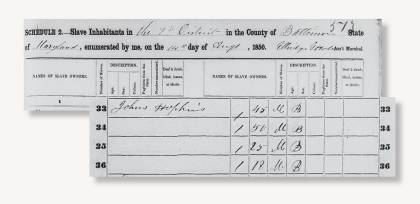

Allison Seyler didn't set out to complicate the university's understanding of its founder. In 2018, the archivist and public historian became the program manager for Hopkins Retrospective, the exploration of the university's history that's become a digital repository for stories, pictures, and perspectives. In preparation to co-teach a spring 2020 class about 19th-century Baltimore during Mr. Hopkins' lifetime, she reached out to a former mentor, retired Maryland State archivist Edward Papenfuse, A&S '69 (MA), '73 (PhD), who has taught classes about, and is currently researching, Hopkins' business history. He mentioned to her that he may have found evidence that Hopkins held enslaved people. Seyler, who spent four years working on the Maryland State Archives' Legacy of Slavery in Maryland project, immediately went looking through slave schedules from the U.S. census records. Maryland submitted two sections to the 1850 census: a Census of Population listing free people and individuals living in corresponding households, and a Census of Slaves that shows the heads of households along with any enslaved individuals therein. These documents showed that Johns Hopkins held four enslaved men in 1850. The 1840 census shows one enslaved person living in the founder's household.

What these recent findings mean for the university and its namesake, both then and now, is what university leadership aims to explore. In a joint statement to the university community in December, President Ronald J. Daniels; Paul Rothman, dean of the medical faculty and CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine; and Kevin Sowers, president of the Johns Hopkins Health System and executive vice president of Johns Hopkins Medicine, announced the results of a preliminary investigation, prompted by the recent discovery, which contradicts the previously accepted history that Hopkins' journey from farmer's son to businessman, abolitionist, and future philanthropist was shaped by his father's emancipation of the family's enslaved workers in 1807.

"All institutions tell stories about themselves," says Martha Jones, a Krieger School history professor and 19th-century Black history expert who confirmed that the Johns Hopkins named in the census documents is indeed the benefactor of the university and hospital. "The United States has an origin story, which is very much subject to debate in 2021—case in point the juxtaposition of The New York Times' 1619 project with the former White House's 1776 Commission. That is a debate about an origin story, about archives, about periodization, about interpretation, and more. And our university, like all universities, has told a story about itself that turns out to be perhaps more grounded in myth and misunderstanding than in the historical archive. In this sense, we're looking to examine myths and stories that we tell about ourselves and to make it possible for us to replace those with histories."

The Hard Histories at Hopkins project, led by Jones, is the university's effort to examine the stories it tells about itself. Launched in fall 2020 as a collaboration between the SNF Agora Institute and Hopkins Retrospective, Hard Histories aims to examine the role that racism and discrimination have played at the university. This spring semester, Jones began a three-year research seminar that brings undergraduates into the ongoing work that she and graduate teaching assistant Malaurie Pilatte are doing in various Maryland archives related to the Hopkins family story and the history of the university.

With a scarcity in this historical record, however, there won't be much to go on.

"One of our approaches is to collect as many small, shardlike pieces of evidence as we can to see what they add up to as we assemble them," Jones says. "As we collect pieces of evidence, we're not always sure how or even if they fit with a broader story. We will continue to do that work, over months and years, to see what we can narrate about the experience, for example, of the enslaved people in Mr. Hopkins' household. On the other hand, we appreciate that the silence in the archive is an artifact of slavery and that part of what being enslaved meant was that the archive necessarily and self-consciously privileged the perspective of Mr. Hopkins and people like him. There are things we cannot know about the enslaved people in his household, about their lived experiences, and we have to take that as a point of reflection in this work that the violence of slavery took many forms."

Jones turned to the census records and other material in the National Archives, Baltimore City directories, and various other paper ephemera housed at the Maryland State Archives, where she previously spent 15 years doing research for her multiple-prize-winning book Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, which examines how Black Americans influenced the idea of American citizenship in the 19th century specifically through the activism of free Black Baltimoreans. Still to come in the research into Hopkins' history: deep dives into the archives of Anne Arundel and Baltimore counties (currently not digitized), as well as into the voluminous minutes from Quaker Society of Friends' archives at various Baltimore meeting houses, and more.

Jones posted a preliminary report of her findings to the Hard Histories website in December 2020 when the university made the announcement about the census records. It includes what Jones has been able to verify thus far, as well as a number of questions that remain: What were the names of the enslaved people in Hopkins' household, what became of them, and do they have any living descendants? What can we say, based on evidence in the historical record, about Hopkins' views on the anti-slavery movement or the Union? And is there any evidence that Hopkins was an abolitionist?

At present, Jones hasn't found any. "A question for us as a community to ask is, How does it change how we think about who we are, how we've evolved, where we want to go in the 21st century, and how we get there?" Jones says. "If we understand that our founder and benefactor was someone who benefited from and was complicit with the institution of slavery, rather than an abolitionist, there's not a straightforward social scientific answer to that." Rather, she says, it's a cultural question.

This cultural question is the biggest challenge Johns Hopkins will struggle with, as it's not one a university can answer by itself because systemic white supremacy isn't unique to higher education or education in general. It's foundational to this country, which is part of the reason why the University of Virginia started the Universities Studying Slavery consortium in 2014, as universities started digging into their own pasts in the early 2000s.

"No single university, or 10 universities, can fully answer for America's role in benefiting from and perpetuating slavery and racism," says Kirt von Daacke, A&S '00 (MA), '05 (PhD), a University of Virginia history professor, assistant dean, and co-chair of the UVA President's Commission on Slavery, which led to the Universities Studying Slavery consortium. "But universities working together can come up with projects that we've been calling 'repair initiatives' that may be able to model ways to have those discussions."

Von Daacke says when Universities Studying Slavery first started there were about four other participating universities and this "consortium" was run out of his email's inbox. When Georgetown University joined in 2016 following its investigation into the 272 enslaved people sold by Jesuits in 1838 to keep the university afloat, interest increased dramatically. Today, more than 70 universities around the United States and in the United Kingdom are participants, including Johns Hopkins, but the "repair initiatives" that von Daacke wants to catalyze are still in development, owing to the challenges of what he calls connecting the dots of the past to the present.

He cites a quote from Craig Steven Wilder's 2013 book Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities, a look at multiple universities' ties to slavery: "The academy never stood apart from American slavery—in fact, it stood beside church and state as the third pillar of a civilization based on bondage."

"You can extend that," von Daacke says. "If that's how universities are created, when slavery goes away, why would we assume that they suddenly stop not only benefiting from these systems of power and domination but actively perpetuating them. That's a real question, and if we're not connecting those kinds of dots, what are we even doing this work for?"

While this reexamination of histories at Hopkins and other institutions is of interest to their students, staff, employees, and the communities in which they're embedded, it's important to place that dot-connecting work into a larger context. The Ebony and Ivy book that von Daacke mentions followed Brown University's early 2000s research into how its founding family benefited from the Rhode Island slave trade. That reconsideration was launched by then Brown President Ruth Simmons, the first Black president of an Ivy League school, on whose shoulders von Daacke says the Universities Studying Slavery impetus stands.

These institutional investigations are taking place during a period of increasing political polarization, and von Daacke says that grassroots advocacy, student protest, and other forms of activism have pushed some universities to join the Universities Studying Slavery project. He notes the spike of interest during the summer 2020 nationwide protests following George Floyd's murder by Minneapolis police.

A diverse range of contemporary scholars are seeking underrepresented narratives in archival materials, producing new scholarship that's challenging conventional histories in their fields. "Archivists and librarians themselves," as Seyler told me, "are recognizing that the ways in which institutions collect and provide access to materials also need to be more diverse and inclusive, addressing the inclusivity of what items are deemed historical and increasing accessibility of who's able to conduct research in them." None of which may be explicitly related to the university's own investigations, but it is important to recognize multiple viewpoints. Yes, Johns Hopkins' relationship to slavery is of interest to the Hopkins and Baltimore communities. But the relationship to slavery of a 19th-century Quaker businessman in a Mid-Atlantic border city whose wealth created institutions that continue to exert cultural, economic, and political power in the 21st century is an interesting American narrative.

Universities recognize that the enlightened self-interest of reexploring their relationships with the cities in which they reside has a contextual element, too, given that anchor institutions historically have not always been good neighbors. This can make connecting those dots between the past and the present complicated and potentially conflictive.

"You're going to run into the sort of fear-based perspective about this work, that talking about Hopkins' past in ways that don't shed positive light on him is somehow bad for the brand," von Daacke says. "We're learning that's not really true. This work is actually good for the brand because it fits with everyone's mission and strategic visions about education, producing new knowledge and creating engaged citizen leaders. You can't do that if you're completely unwilling to investigate your own past."

The UVA President's Commission on Slavery that von Daacke co-chairs led the charge to build and approve the Memorial to Enslaved Laborers on campus in response to student calls for memorialization and honoring contributions of the enslaved people who constructed the university. But contemporary truth-telling about slavery, and its enduring legacies, doesn't always connect with university-led equity and inclusion efforts around areas such as housing, health care, and education in disinvested Black communities. The work of making those connections "requires really profound listening and humility, and that's where universities often struggle," von Daacke says. "Even though we have a large arsenal of expertise and resources that we can use to address problems, we have to stop, let someone else tell us what the problem is, and then propose solutions to it."

Christopher S. Celenza, the new dean of the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, agrees. The former Krieger School vice dean and Johns Hopkins University vice provost became dean of Georgetown College at Georgetown University in 2017, a year after Georgetown leadership announced its investigation into the 1838 sale of enslaved people. Celenza says by the time he arrived Georgetown had completed its initial findings and plans to rename two buildings named after two Jesuits who played significant roles in that transaction. "What stayed with me is the fundamental consciousness behind what they were doing," he says. "One, of course, is recognizing the past truthfully, memorializing it, and in their case apologizing for it. But what became as important to me was committing to doing a deep institutional dive into what things are we doing now that might 200 years from now seem equally cruel or misguided."

That focus on the present is on Celenza's mind as he returns to Hopkins, where he's part of a senior leadership group that will support Jones' work and help develop a set of initiatives that explore our historical connections to slavery. "The whole point about confronting the past is asking how we can make sure that we're committed as an institution to addressing, first and foremost, anti-Black racism," he says. "We have to say that. We really need to understand that the Jim Crow period through redlining in urban areas had immense structural effects on Black communities. We need to reach out and make sure we're listening, openly and humbly, to what our community has to tell us—because I do think that this revelation about Johns Hopkins has caused understandable pain to members of our community, even if they weren't surprised."

Lawrence T. Brown wasn't. "I knew in East Baltimore they had a nickname for Hopkins—the plantation—so finding this out actually helps illuminate and clarify why people use that language 150 years later," says Brown, a public health researcher whose recent Johns Hopkins University Press book, The Black Butterfly, connects the structural racism that Celenza mentions above to the historical trauma of generational displacements of Black populations.

"I'm not from Baltimore, so hearing how born-and-raised Black people in Baltimore weren't surprised when hearing the news, that on some level showed me this cultural truth was rooted in historical evidence," Brown continues, adding that he doesn't know if that cultural truth would've been any different if the historical evidence proved Hopkins didn't own enslaved people. "I think the cultural truth may be in some ways stronger than some of the historical evidence. I mean, you didn't have to be a slave owner to benefit from slavery. The Baltimore Sun ran ads about runaways and selling people. Bars and hotels had agreements with slave traders scouting for runaways. I think for Black folks, the entire economy was built around this."

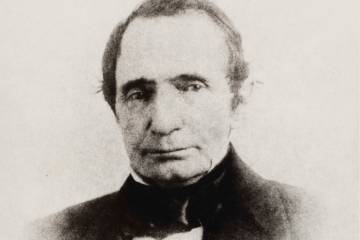

Brown's observation of one East Baltimore cultural truth echoes the cultural question that Martha Jones says the university has to face when confronting its own mythmaking. Johns Hopkins was not a man of letters, and whatever correspondence and personal paper ephemera he possessed were destroyed or lost to time. What we know about our namesake comes primarily from Johns Hopkins: A Silhouette (1929, Johns Hopkins University Press), a short and generous biography written by his grandniece Helen Hopkins Thom. The book's first chapter is a melodramatic rendering of Johns Hopkins' father's faith-informed decision to free the enslaved people on his Anne Arundel County plantation in 1807. Jones found some earlier mentions of that manumission and Hopkins' ostensible abolitionism in his Baltimore newspaper obituaries, but when Hopkins' life story is recounted Thom's book provides the bulk of the broad strokes. Why that narrative is only being challenged now is one of those cultural questions for which Hard Histories at Hopkins may provide an answer.

Also see

The archival record, however, is only going to be able to illuminate so much. "I think it's going to be impossible to find something that's written in Johns Hopkins' own hand telling us about what happened, or his relationship with these enslaved individuals. That record likely just doesn't exist," Seyler says. "We can make educated suggestions or lay out scenarios that could've happened based on the archival evidence that we do find, but I think that people have to be prepared that there will be some ambiguity."

That ambiguity is the silence in archives that Jones identified as an artifact of slavery, reminders that "hard histories" being explored by this research project are the lives of the six enslaved men noted in those census records, men whose entire record of their existence on this planet, currently, is notations of their ages and gender made more than 170 years ago. Doing this kind of history research, Jones says, "certainly has made clear to me that as a country, as a collective, as a nation, we really have a distance to go in our shared understanding of what slavery was and how to regard it as a facet of the past," Jones says. She contrasts the U.S. with France, another country with a long and deeply troubled relationship to slavery and the slave trade. On May 21, 2001, the French Parliament adopted Act 2001-434, whose first article, translated, reads: "The French Republic recognizes both the trans-Atlantic and Indian Ocean Negro slave trade, on the one hand, and slavery itself, on the other, that were practiced from the 15th century, in the Americas, the Caribbean, the Indian Ocean, and Europe against African, Amerindian, Malagasy, and Indian populations, as constituting crimes against humanity."

"That is a very special and distinct designation when it comes to human atrocities of the past," Jones says. "And in this country, we're not so sure. Americans understand remarkably little about what slavery was and imagine that there might've been something benevolent or even humanitarian about holding other human beings as property, I'm afraid. That's remarkable to me, and an insight that really reaffirms my commitment to the research and to the teaching and to the public work around the history of slavery."

A previous version of this story misstated the number of enslaved men held by Johns Hopkins in 1850. The magazine regrets the error.