Enslaved families once lived and worked for the people who owned the land that Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus now occupies.

Simply acknowledging that fact and exploring the historical significance of it occupies the heart of a multiyear research project at Johns Hopkins, part of a broader movement toward reconsidering the way we talk and think about historic house museums and heritage sites in America. The project inspired a spring semester class on the topic as well as a new, soon-to-debut tour script at Homewood Museum.

"We're trying to rethink the stories we present here and shift toward a social history focus," says Julie Rose, the museum's director and curator.

The Palladian-style, Federal-era mansion that is home to Homewood Museum was built in the early 19th century for Charles Carroll of Homewood; his wife, Harriet Chew Carroll; and their five children. Rose notes that since it opened as a museum in 1987, the curatorial focus has been similar to that of most historic house museums in the latter half of the 20th century, with a focus on the architecture of the building and its affluent principal occupants.

Charles Carroll of Homewood came from one of Maryland's most distinguished families. His father, Charles Carroll of Carrollton, was a Declaration of Independence signatory and Maryland's first senator. His grandfather, Charles Carroll of Annapolis, was the son of one of Maryland's early settlers, Charles Carroll the Settler, who acquired nearly 50,000 acres of land before his death in 1720. That land produced tobacco, cotton, wheat, and other grains, and it provided a fair share of the family's wealth over the next two centuries. And from the time of Charles Carroll the Settler's arrival in 1688 on through emancipation, the Carroll family was one of the largest slave-owning families in the state.

The Homewood estate was never a large-scale working farm, but it was an affluent family's country house and home to several families. Rose says that, to their current knowledge, up to 36 enslaved people lived at Homewood when the Carrolls were there.

"The new tour, Families at Homewood, focuses on three of the families that lived at Homewood: two enslaved and one that was slave-holding," Rose says. "We're telling the stories of Cis and Izadod Conner, who raised a family here. They had six children and, later, they had as many as 13 children. What happened to them? What were their lives like? These are the kinds of questions we can ask when we start to look at this [historic house] with fresh eyes."

More Than A Name: Enslaved Families at Historic Homewood, an exhibition co-curated by eight undergraduates in a spring 2018 class offered by the Program in Museums and Society, focuses on those three families: the Carrolls, the Conners, and William and Becky Ross and their children. The exhibition, which runs through May 27, grew out of the "Enslaved at Homewood" research project, an effort to uncover more information about these enslaved families and individuals that is funded by a Maryland Heritage Areas Authority grant.

"The historic house story has traditionally always been about the family, the white family that owned the house," says Abby Burch Schreiber, the researcher who, along with Rose, taught the More Than a Name class and co-curated the exhibition. "As a way to kind of emerge from that tradition in a fresh way, we're thinking of families. The family, and the numerous families here—because there has never been a concerted effort to systematically understand even the basic circumstances of slavery here."

Image caption: Julie Rose and Abby Burch Schreiber

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Schreiber, who graduated from Johns Hopkins in 2006 with degrees in history and anthropology, worked as a Homewood Museum staff member for a year before going on to earn a PhD in history. Her dissertation focused on Baltimore merchants from 1790 to 1830.

Catherine Rogers Arthur, Homewood Museum's previous director and curator, knew of Schreiber's interest and expertise in mid-Atlantic material culture and history during the era of Homewood 's construction and early years, so she reached out to her about the "Enslaved at Homewood" project.

"As we started this project about three and a half years ago, family letters were mostly what we used," Schreiber says. "Those were the sources that we had available."

In April 2015, Schreiber delivered a talk during an alumni weekend panel discussion that drew heavily on stories she gleaned from Carroll family correspondence and newspapers. Titled "Enslaved at Homewood: Sources on Individual Experiences," it was a frank, sobering discussion of the people and what their lives might have been like. Schreiber made clear that if one of the missions of a museum is to tell the stories of history, leaving out certain participants in that history paints an incomplete picture.

Also see

"You can't understand an estate like Homewood, a farm that had agricultural laborers but also a grand mansion that had a number of household staff, [without understanding the people who were doing the work]," Schreiber said during the talk, noting that Homewood was part of a larger system of labor and agriculture among the Carroll family properties. The story of the Carrolls and their lifestyle at the estate, by necessity, she said, needs to include the stories of everyone else who lived on the farm. "We need to talk about slavery more at Homewood," she said.

In recent years, many historic homes, heritage sites, and history museums have begun exploring ways to tell such "difficult history." Historian and curator Phillip Seitz worked with the Cliveden historic mansion in Germantown, Pennsylvania. In an essay for Curator: The Museum Journal titled "No More White History," he discusses the challenges of incorporating the history of slavery into a historic house's curatorial program but notes that, in doing so, the strong public response has the capacity to turn historic homes into spaces of deep reflection.

Rose, Homewood Museum's director and curator, agrees. In her 2016 book, Interpreting Difficult History at Museums and Historic Sites, she writes about the Magnolia Mound Plantation house in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which introduced the stories of enslaved people into its tours and storytelling to develop strategies for making difficult history part of a curatorial practice.

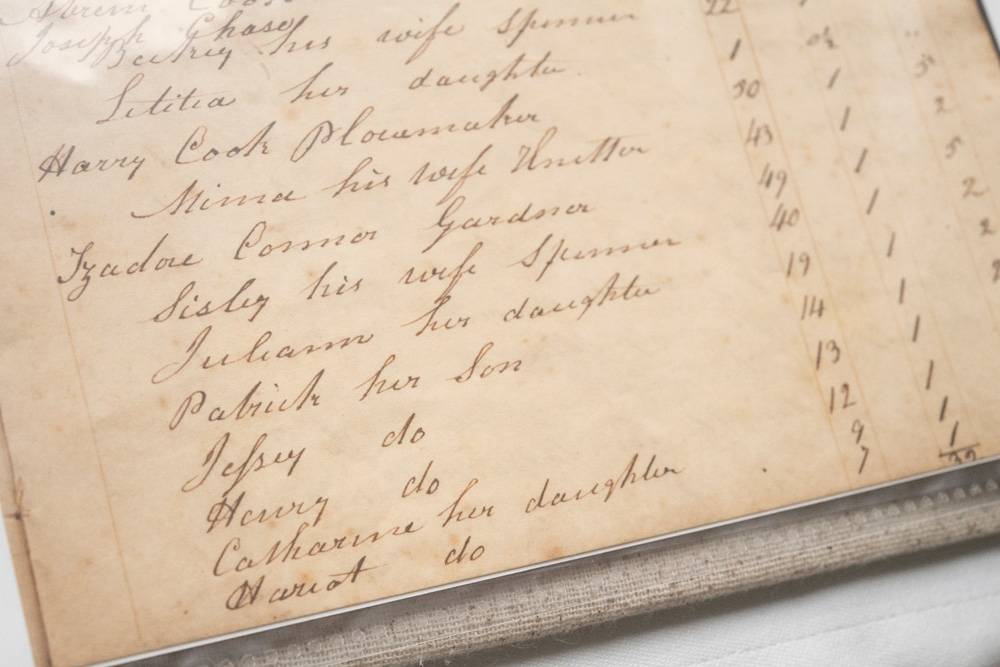

Image caption: A 19th century ledger lists the names and ages of people enslaved on the Homewood estate

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

She notes that there will be pushback, as the telling of oppressive history can make people uncomfortable. One common argument against incorporating the history of enslaved people, she says, is that, due to the scarcity of primary sources, the history is difficult to tell meaningfully and accurately. But, Rose explains, "resistance to interpreting slavery is not about scarcity of documentation." Rather, using the supposed scarcity of documentation to excuse engagement is a form of resistance, as are denial, sarcasm, and apathy.

Thanks to the "Enslaved at Homewood" grant and the digitization of archival materials, Schreiber was able to explore a much wider selection of material. She dug through tax records; church records; manuscripts at the Maryland State Archives, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the Maryland Historical Society; and more.

"Once we got the funding for the project, I was able to uncover many more sources, and as we've been continuing to develop the tour, we've been finding even more," Schreiber says. "The Maryland State Archives has done a huge project on the digitization of the records related to slavery, so there's a lot more available online now than there was even 10 years ago."

Rose and Schreiber understand that the history of Homewood is an evolving narrative, as they and their students turn the information they encounter into the stories that are part of the exhibition and the new tour script. What the "Enslaved at Homewood" grant has enabled the museum to achieve is a step toward presenting a more inclusive interpretation at Homewood Museum and providing a richer understanding of the place where the Johns Hopkins University is located. But it's still just a first step.

Rose says that when she and Schreiber first started writing the new tour script last summer, they had a certain set of questions they assumed they wanted to answer.

"As we found new material, we started to ask different questions," Rose says. She notes that the museum's docents will be the first trained with the new tour, and she imagines that once the public engages with it, new questions will emerge from that process, too. "This [project] is really just the beginning of the story."