While her friends and peers were settling down, getting married, and leading seemingly stable lives, aspiring writer and comedian Audrey Murray was still floating in her late 20s. She had done a stint working for an environmental consulting company that required her to fly out to different regions of the country to count light bulbs in strangers' homes. She spent five off-and-on years in Shanghai, teaching English and taking up improv comedy in her spare time. And then, in 2015, she impulsively booked a one-way ticket to Kazakhstan, commencing a yearlong journey through the former Soviet Union.

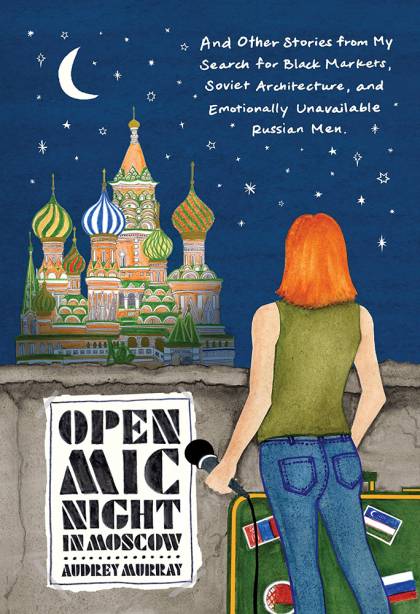

Image caption: Audrey Murray

In her memoir, Open Mic Night in Moscow (William Morrow, 2018), Murray, A&S '09, touches on a couple of motivations for her trip: a long-term obsession with all things Russian, sparked by a couple of Russian ex-boyfriends, and a personal struggle with whether she wanted to "settle down," as everyone around her seemed to be doing.

Her writing offers a warts-and-all glimpse into her experiences, unfolding diarylike as it details her earnest, awkward, thrilling, and profoundly human encounters in the 11 countries she visited. Tales of small kindnesses—a Lithuanian woman helping her find her Couchsurfing hosts in the middle of the night—interweave with short character studies, like the man Murray refers to as "the Kazakh cowboy," who lets slip some deeper anguish behind his stony exterior. When Murray mentions writing a book, the man tells her that he became sober as a result of a book his son wrote. "It was about how I drank too much," he tells her. "And I hurt my family."

These oft-enigmatic observations of passing faces and places—dilated with useful context on the lingering effects of authoritarian rule—are offset by the author's comical, persistent lack of preparation. On the flight to Kazakhstan, when she tries to "pantomime the not-so-charades-friendly phrase bottled water," she realizes that six weeks of Rosetta Stone wasn't enough time to teach her essential Russian phrases. She also erroneously includes Mongolia in her itinerary, not realizing until she gets there that it hadn't been part of the Soviet Union—but here she has a spiritual moment in a Buddhist temple and helps feed baby goats. Swaying from openness to anxiousness about what's around the corner, Murray considers the serendipity of accidents that compose life.

The book came together with a touch of serendipity, too. Murray's sorority sister Stephanie Delman, A&S '11, became the literary agent who would push the former Writing Seminars student to follow through on writing and revising the memoir. Delman and Murray sold the proposal to HarperCollins imprint William Morrow by way of editor Emma Brodie, A&S '11, whom the author befriended in a playwriting class her senior year. Her film and TV agent, Laura Gordon, A&S '09, was a classmate in a narrative fiction class their sophomore year.

Image credit: William Morrow

Murray's journey-as-escape from the pressures of entering into a contractually binding partnership takes an ironic turn, as nearly every person she meets immediately asks if she has a husband and kids. (The question is usually intended as a polite conversation starter.) In response, she often lies because it's easier and avoids possible judgment. But on the page, these exchanges trigger both long-winded rebukes of patriarchal expectations and memories of those aforementioned Russian ex-boyfriends, Oleg and Anton. Oleg remains a good friend, but she is particularly hung up on Anton, processing bits and pieces of their relationship throughout the trip, though they broke up two years earlier.

Every few countries—often after something terrifying or incredible happens—Murray's attitude pivots and her resolve strengthens. She visits Anton's birthplace of Belarus, figuring it ought to satisfy some malingering desire, even if it risks more emotional pain. Meeting up with Anton's friends in Belarus feels awkward and strange, but that's part of the appeal. "I'm showing myself that I can get through it," she writes. For a long time, she had thought she needed Anton to show her around Belarus and translate for her, but once there, she reckons with her feelings for him and considers how the relationship may have held them both back. "It's a weird moment," she writes, "when you realize the thing you think you want doesn't actually exist."

Murray's travels conclude in Moscow, where, true to form, she has nothing precisely planned, but she finds herself onstage at an open mic comedy night. Stand-up comedy is somewhat new in Russia, Murray notes, and the crowd responds to every joke "with long, reasoned reactions." But she wakes up the next morning with a sense of accomplishment. "Everything I've done in the former Soviet Union has seemed as inconsequential and simple as putting one foot in front of the other," she writes. It's just that a former version of Murray would've doubted her ability to pull it off.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged writing seminars, memoir