Every May, Larry Scarber travels from his hometown of Snowflake, Arizona, to Baltimore to participate in a Johns Hopkins-led study of Alzheimer's disease.

He rolls up his sleeve for blood draws and patiently answers questions about paragraphs that were just read to him to see how much he can remember. He stays as still as he can in the MRI machine and during PET scans of his brain. He hunches over on an exam table so a needle can be inserted into his lower back to draw out spinal fluid.

It's a big commitment, and sometimes uncomfortable. He lives about three hours from the Phoenix airport, so he flies to Baltimore the night before his appointments. At Johns Hopkins, he tends to panic in the MRI machine and is considering having his personal physician prescribe a sedative for future visits.

Yet, he has dutifully shown up for these tests and procedures for more than 20 years, even though he knows there's little chance he'll personally benefit from the data that Johns Hopkins researchers are collecting from him.

Scarber, 68, along with three of his sisters, are part of a cohort of more than 470 participants in the BIOCARD study, an unusually detailed and enduring longitudinal study of Alzheimer's disease, which began in the National Institutes of Health in 1995 and moved to Johns Hopkins in 2009.

"We just felt like if there was a chance to find an answer or remedies, long- or short-term, whether it was for us or our kids or our grandkids, then it was worth trying," says Scarber, a retired police chief whose mother had the disease. He looks forward to the annual East Coast treks, he says, as this gives him an opportunity to see family members who live in the area.

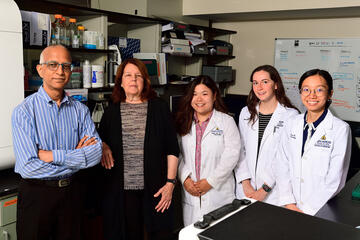

Neurology professor Marilyn Albert, who has led the study since it came to Johns Hopkins, says participants like Scarber are essential to developing new insights and eventual treatments for a debilitating and still incurable disease.

"The goal is to understand how early we can intervene, and what markers are going to tell us when that should be," Albert says. "To get this kind of information means following people for decades. We're so lucky to have people who volunteered and understand and are willing to commit the time."

BIOCARD's investigators are about to submit a request for the next round of five-year funding from the National Institute on Aging—money that covers the procedures that provide state-of-the-art information about brain structure and function in the participants.

Importantly, the Johns Hopkins Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, which helps support much of the infrastructure essential for the study, recently won funding for the next five years, resulting in 40 years of continuous support from the NIH.

Scarber and his siblings signed on when they were in their 40s and 50s, at a time when researchers did not know how or even when Alzheimer's disease began. Like most participants, they had a family connection to Alzheimer's, but were disease-free themselves.

Now, about a third of the participants have developed either mild cognitive impairment or dementia, and researchers have learned that the plaques and tangles that characterize Alzheimer's disease develop long before symptoms appear. They know the specific part of the brain where they form and are now looking at changes that occur long before they accumulate to an abnormal level.

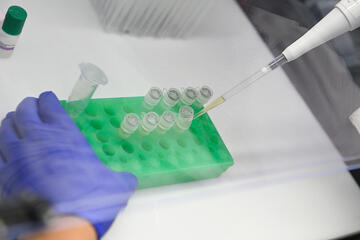

Recently, BIOCARD data contributed to the development and validation of a blood test for early Alzheimer's detection, approved by the Food and Drug Administration for people who are 55 or older, with diagnosed cognitive declines.

Unusually engaged participants

Four years after the NIH shuttered the BIOCARD study in 2005, Albert and Johns Hopkins won permission to continue it.

The project arrived in Baltimore in the form of 56 boxes of documents and six freezers full of blood and spinal fluid samples, she says. "We had to make sense of it, and that actually took us quite a while. We started contacting the participants right away."

Image caption: Marilyn Albert

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

Maura Grega and Leonie Farrington, nurses working with Albert, tracked down every participant still alive, told them the study was resuming, and asked if they wanted to get back in the routine of annual tests and appointments. Remarkably, all but a handful said yes.

"Typically, longitudinal studies have a high dropout rate," Grega says. "That is not the case with this group of people. This is an incredibly dedicated group of participants."

Of the original cohort of 350, about 325 are alive and participating, says Albert. An additional 150 have been added in the last few years. The original cohort started with a mean age of 56; the newer cohort has a mean age of 60, and more closely mirrors the ethnic diversity of the general population. Both groups are about 60% female, 40% male.

Participants are scattered across the United States and Canada—plus one in Fiji. They rely on Grega and Farrington to set up appointments, book hotels, set up car transportation to and from appointments, and even arrange flights when requested.

"We've developed a really wonderful relationship with all of these participants over time," Grega says. "It takes years and years to get to this point, and now we're there. It's incredibly important for us to be able to continue."

Participants can opt out of specific procedures, or even skip a year, yet few do. Albert also notes that the procedures have grown more technologically demanding, requiring more time from participants but allowing researchers to zero in on the specific parts of the brain where plaques and tangles develop.

Albert also leads an annual online symposium that keeps interested participants up to date on the research that their commitment supports. In 2024, the topics included updates on how researchers are pinpointing the precise location of biomarkers that are early indicators of disease.

Alzheimer's disease in the family

Like other participants, Scarber knows firsthand how grindingly difficult Alzheimer's can be. When his mother's disease progressed to the point that she could no longer live on her own, she moved in with Scarber and his family. He slept on a cot outside her bedroom door, to stop her from leaving the room and wandering around the house, getting more confused and frantic by the minute. "She didn't recognize anything," he said.

She lived her last few years in a memory care facility in Globe, Arizona, before she died in 2002.

Scarber's sister, Janet Bearden, who was living near Washington, D.C., at the time, had already enrolled in the BIOCARD study, and urged her siblings to sign on. Scarber agreed, as did two more sisters—Linda Crooks, who lives near Portland, Oregon, and Louise Flanagan, of Missoula, Montana. Each participant also has a study partner, usually a spouse or sibling, who is interviewed every year.

"Having seen firsthand the effects of Alzheimer's disease, I'm glad that there is research being done," Scarber says. "If there's a cure out there that can slow the progression, I'm all for that. There's hardly anyone who is not affected by dementia. I hear from friends who say, my sister has this, or my mom had it, or a co-worker had early onset."

Another participant, Patricia Coffey, 84, of Potomac, Maryland, remembers an aunt who was so debilitated that she forgot how to eat. The former International Monetary Fund employee worried about her own memory and joined BIOCARD in 2002, rejoining when it moved from the NIH to Johns Hopkins.

"They make it a privilege," she says of the annual trips to Baltimore, where the study pays for her hotel, meals, and transportation to and from Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.

She says even the spinal tap is "a piece of cake" because the technicians are so skilled. "My vertebrae are compressed, so they use a child-sized needle and it takes longer to get the spinal fluid out," she says. "It's not comfortable, but it's not bad."

The researchers do not diagnose participants, but they can provide an annual letter, if requested, saying whether the patient's cognition is in the normal range. They'll also give information to a participant's physician, if requested. Both Scarber and Coffey say they look forward to getting that letter each year, which so far has been reassuring.

"I am single with no immediate family, and I don't think my more distant relatives should have the responsibility of looking after me in my old age," Coffey says. "Being in the study enables me to stay on top of my cognitive status so that if it looked like I was developing Alzheimer's, I could make plans for my senior years while I still know my nose from my toes.

"It is very important to me with respect to how I will continue to lead my senior years, but it is even more important that I feel like I'm contributing to a study that I can see is extremely valuable."

Posted in Health

Tagged alzheimer's disease, aging, johns hopkins medicine, nih