- Name

- Roberto Molar Candanosa

- rmolarc1@jh.edu

- Office phone

- 443-997-0258

- Cell phone

- 443-938-1944

The James Webb Space Telescope has captured its first direct images of carbon dioxide in a planet outside the solar system in HR 8799, a multiplanet system 130 light-years away that has long been a key target for planet formation studies.

The observations provide strong evidence that the system's four giant planets formed in much the same way as Jupiter and Saturn, by slowly building solid cores. They also confirm Webb can do more than infer atmospheric composition from starlight measurements—it can directly analyze the chemistry of exoplanet atmospheres.

Key Takeaways

- The Webb Telescope captured its first direct images of carbon dioxide in an exoplanet.

- The findings suggest planets in a system 130 light-years away likely built up solid cores before attracting gas, much like our solar system’s gas worlds.

- Webb’s coronagraphs allow direct atmospheric analysis, paving the way for deeper studies of distant worlds.

"By spotting these strong carbon dioxide features, we have shown there is a sizable fraction of heavier elements, such as carbon, oxygen, and iron, in these planets' atmospheres," said William Balmer, a Johns Hopkins University astrophysicist who led the work. "Given what we know about the star they orbit, that likely indicates they formed via core accretion, which for planets that we can directly see is an exciting conclusion."

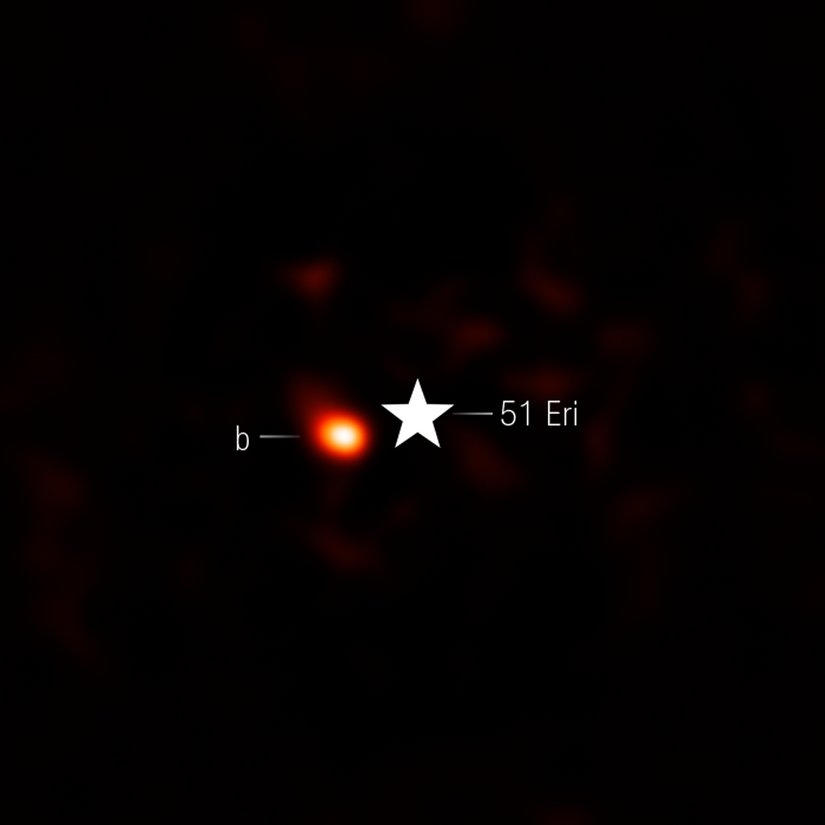

An analysis of the observations, which also included a system 96 light-years away called 51 Eridani, appears in The Astrophysical Journal.

Image caption: The clearest look yet in the infrared at the iconic multi-planet system HR 8799. Colors are applied to filters from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera). A star symbol marks the location of the host star HR 8799, whose light has been blocked by the coronagraph. In this image, the color blue is assigned to 4.1 micron light, green to 4.3 micron light, and red to the 4.6 micron light.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, W. Balmer (JHU), L. Pueyo (STScI), M. Perrin (STScI)

HR 8799 is a young system about 30 million years old, a fraction of our solar system's 4.6 billion years. Still hot from their violent formation, HR 8799 planets emit large amounts of infrared light that give scientists valuable data on how their formation compares to that of stars or brown dwarfs.

Giant planets can take shape in two ways: by slowly building solid cores that attract gas, like our solar system, or by rapidly collapsing from a young star's cooling disk into massive objects. Knowing which model is more common can give scientists clues to distinguish between the types of planets they find in other systems.

"Our hope with this kind of research is to understand our own solar system, life, and ourselves in comparison to other exoplanetary systems, so we can contextualize our existence," Balmer said. "We want to take pictures of other solar systems and see how they're similar or different when compared to ours. From there, we can try to get a sense of how weird our solar system really is—or how normal."

Very few exoplanets have been directly imaged, as distant planets are many thousands of times fainter than their stars. By capturing direct images at specific wavelengths only accessible with Webb, the team is paving the way for more detailed observations to determine whether the objects they see orbiting other stars are truly giant planets or objects such as brown dwarfs, which form like stars but don't accumulate enough mass to ignite nuclear fusion.

"We have other lines of evidence that hint at these four HR 8799 planets forming using this bottom-up approach," said Laurent Pueyo, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute who co-led the work. "How common is this for long period planets we can directly image? We don't know yet, but we're proposing more Webb observations, inspired by our carbon dioxide diagnostics, to answer that question."

The achievement was made possible by Webb's coronagraphs, which block light from bright stars as happens in a solar eclipse to reveal otherwise hidden worlds. This allowed the team to look for infrared light in wavelengths that reveal specific gases and other atmospheric details.

Targeting the 3-5 micrometer wavelength range, the team found that the four HR 8799 planets contain more heavy elements than previously thought, another hint that they formed in the same way as our solar system's gas giants. The observations also revealed the first-ever detection of the innermost planet, HR 8799 e, at a wavelength of 4.6 micrometers, and 51 Eridani b at 4.1 micrometers, showcasing Webb's sensitivity in observing faint planets close to bright stars.

Image caption: Webb captured this image of Eridani 51 b, a cool, young exoplanet that orbits 11 billion miles from its star. This image includes filters representing 4.1-micron light as red.

Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, W. Balmer (JHU), L. Pueyo (STScI), M. Perrin (STScI)

In 2022, one of Webb's key observation techniques indirectly detected carbon dioxide in another exoplanet, called WASP-39 b, by tracking how its atmosphere altered starlight when it passed in front of its star.

"This is what scientists have been doing for transiting planets or isolated brown dwarfs since the launch of JWST," Pueyo said.

Rémi Soummer, who directs the Russell B. Makidon Optics Laboratory at the Space Telescope Science Institute and previously led Webb's coronagraph operations, added: "We knew JWST could measure colors of the outer planets in directly imaged systems. We have been waiting for 10 years to confirm that our finely tuned operations of the telescope would also allow us to access the inner planets. Now the results are in, and we can do interesting science with it."

The team hopes to use Webb's coronagraphs to analyze more giant planets and compare their composition to theoretical models.

"These giant planets have pretty big implications," Balmer said. "If you have these huge planets acting like bowling balls running through your solar system, they can either really disrupt, protect, or do a little bit of both to planets like ours, so understanding more about their formation is a crucial step to understanding the formation, survival, and habitability of Earth-like planets in the future."

Other authors include Jens Kammerer of the European Southern Observatory; Marshall D. Perrin, Julien H. Girard, Roeland P. van der Marel, Jeff A. Valenti, Joshua D. Lothringer, Kielan K. W. Hoch, and Rèemi Soummer of the Space Telescope Science Institute; Jarron M. Leisenring of University of Arizona; Kellen Lawson of NASA-Goddard Space Flight Center; Henry Dennen of Amherst College; Charles A. Beichman of NASA Exoplanet Science Institute; Geoffrey Bryden, Jorge Llop-Sayson of Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Nikole K. Lewis of Cornell University; Mathilde Mâlin of Johns Hopkins; Isabel Rebollido, Emily Rickman of the European Space Agency; Mark Clampin of NASA Headquarters; and C. Matt Mountain of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

This research was supported by NASA through grant 80NSSC20K0586, with additional support from NASA through the JWST/NIRCam project, contract number NAS5-02105, and the Advanced Research Computing at Hopkins (ARCH) core facility (rockfish.jhu.edu), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) grant number OAC1920103. Based on observations with the NASA/ESA/CSA JWST, obtained at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by AURA Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-03127.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged astrophysics, physics and astronomy, planetary science, national science foundation