- Name

- Jason Lucas

- jlucas27@jhu.edu

- Cell phone

- 443-301-7993

Johns Hopkins University students are working to uncover details about the lives of African American girls who lived at an orphanage once located where the Wyman Park Building now stands, near the southwest corner of the university's Homewood campus.

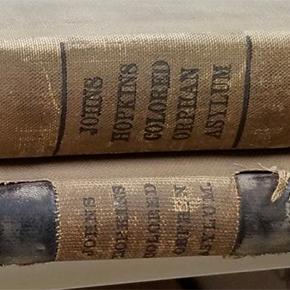

The students were offered an opportunity to discover more when they learned that Heather Cooper—project archivist at the Chesney Medical Archives for the Reexamining Hopkins History initiative, led by Hopkins Retrospective—had recently reprocessed and developed an extensive and detailed new finding aid for the Orphan Asylum collection. Committed to discovering the human side of the asylum's history and telling the story of the boys and girls who lived there, the Hopkins students have learned the identities of more than 200 children. The students accomplished this by researching census data, financial records from the Chesney Archives, and minutes from Johns Hopkins Hospital board of trustee committee meetings.

"What we did not anticipate is that our lab, in the Wyman Park Building, sits on the very site where the orphan asylum once stood," said historian Martha S. Jones, who is leading the course called A Tale of Two Orphanages.

Image caption: The Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum was founded in 1873 and operated from the mid-1890s through the mid-1910s in a building on 31st Street between Remington Avenue and what is now Wyman Park Drive, a location where located the Wyman Park Building now stands.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

The course is part of the ongoing Hard Histories at Hopkins project that examines the role that racism and discrimination have played at Johns Hopkins. Jones and Cooper will be among the participants in a virtual discussion today about what the medical archives can teach us about the history of the institution and its relationship to slavery, racism, and discrimination.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum was founded in 1873 as part of the university founder's death bequest to fund the university and hospital. Starting in 1875, the institution housed African American children ages 5 to 18 who had lost one or both of their parents. It operated from the mid-1890s through the mid-1910s in a building on 31st Street between Remington Avenue and what is now Wyman Park Drive.

"Learning bits and pieces of information has been like finding gold for us," said Matthew Palmer, a senior majoring in history.

In the students' quest to uncover what life was like at the asylum, they've discovered that girls lived there part- or full-time, and the majority of them received training to be domestic servants.

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Alan Mason Chesney Archives

"It's striking for us that at the same time that Johns Hopkins Hospital was steering the lives of Black girls toward domestic service, across the way on the new Homewood campus the university was building a school to prepare young white men for leadership," said Jones, the Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor and director of Hard Histories at Hopkins.

Because the collection doesn't include any of the girls' letters or diaries, Jones said the students' discoveries are important to gain a better understanding about the facility and its inhabitants.

Receipts found in the collection's financial records show how the institution's matrons and "lady managers," prominent white women in Baltimore who managed the asylum, purchased everything from food and sewing materials to medicine and Christmas trees.

"We are at the beginning of recovering the names of the girls from the asylum and trying to transform the story from one about them being unnamed and faceless into a narrative that reveals what they experienced," Jones said.

As the students learn more about the girls who lived at the orphanage, they'll develop blog posts that will be posted on the Hard Histories Substack site.

"I think it's powerful the students realized that it's possible to piece together details about the girls," Cooper said, "even with a collection like ours that reveals more about the people overseeing the asylum than those living there."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society, Community

Tagged community, hopkins retrospective, johns hopkins history, martha jones