As part of a multiyear effort to examine the legacy of slavery and segregation at Johns Hopkins University and Johns Hopkins Hospital, historians gathered for a forum Friday to discuss the methodologies of their ongoing research and the complexities of assembling greater understanding from the fragments of surviving evidence.

"I'm truly appreciative of the extent to which our historians, archivists, and our colleagues from fellow universities, as well as community members in Baltimore and beyond, have undertaken the hard, painstaking work of historical inquiry to forge a more complete and complex picture of our history as an institution and a nation," Johns Hopkins University President Ron Daniels said. "I look forward to learning more in the months and years ahead to better understand our past and ensure that this knowledge shapes our present and future as an institution."

Friday's forum, organized by the university's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and Hopkins Retrospective, explored the complexities of archival research and scholarship around the institution of slavery and its legacies at universities. The virtual event featured panels on research methodologies, how racism and slavery continue to affect institutions, and the future of such research. Panelists included several historians from Johns Hopkins and elsewhere who are engaged in this work.

"Though we may have come late to the writing of a comprehensive institutional history in general, and attending to our connections to slavery and institutional racism in particular, we've now entered into these fields with energy," said Chris Celenza, dean of the Krieger School.

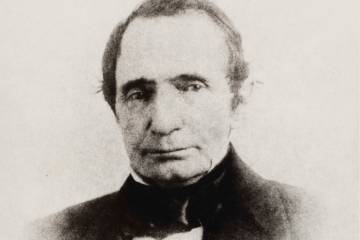

The event comes one year after the university announced the discovery of census records listing enslaved people among those living in the home of university founder Johns Hopkins in 1840 and 1850, with the latter record naming him as the slave owner. Those and other newly discovered or examined records contradicted previous accounts of him as an early abolitionist whose father freed the family's enslaved people in the early 19th century. Since those records came to light, Johns Hopkins faculty and staff have embarked on a multi-year investigation into the legacies of slavery and segregation on the institutions Mr. Hopkins founded, led by its own historians and archivists from the departments of History and the History of Medicine, as well as staff from the Sheridan Libraries and Hopkins Retrospective.

Over the course of the past year, these historians and students working alongside them have pieced together records and data to paint a clearer picture of Mr. Hopkins and the people who may have been enslaved by him and his family, as well as the broader story of the legacies of slavery, segregation, and racism on the university. The deeply researched historical examination is expected to take years to complete.

The team at Chesney Medical Archives at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine has identified collections that will be relevant to researchers as they assess racism and discrimination in the history of Johns Hopkins Hospital and the schools of Medicine and Public Health. This includes compiling a list of collections that document exclusionary policies and practices, the transition from segregation to integration, and the rise of policies for diversity and inclusion. Similarly, the Peabody Institute is in the early stages of plans for research on George Peabody, and the Homewood Museum is planning research into Samuel Wyman, whose family gifted land to Johns Hopkins University in 1902. These investigations are part of the university's pledge, made in July 2020, to examine the history of discrimination at Johns Hopkins and how the university has both reinforced discrimination and served as a force to combat it.

The university has pledged additional institutional resources to the effort, including new investments in the Hopkins Retrospective team to include three additional permanent staff who will expand JHU's capacity for archival work and dissemination and public history education around the sustained reexamination of Hopkins history.

Panelists Friday reflected on the difficulties of reconciling the contradictions of the historical record and the need to avoid simplistic conclusions or uncritical appraisals of historical figures.

Image caption: Erin Rowe (left), associate professor of History, and Martha Jones, professor of History, discuss the ongoing examination of Hopkins history, which includes the university’s connections to slavery, racism, segregation, and discrimination.

"Abolitionists are thought of as so far removed from slavery, some think it inconceivable that an abolitionist could own slaves," said Sasha Turner, Johns Hopkins associate professor of history. "Not so."

Adam Rothman, professor of history at Georgetown University and curator of the Georgetown Slavery Archive, said this work matters because it is so relevant to students.

"Examining the history of our own university is a wonderful opportunity to think about how history affects every one of us, that the history of slavery and racism are not issues for somewhere else," he said. "They happened in our own back yards."

Martha Jones, Society of Black Alumni Presidential Professor at Johns Hopkins and director of Hard Histories at Hopkins, taught courses in the spring and fall semesters seeking to lead students in the development of a more complete picture of the university's history, both as it relates to Mr. Hopkins and to the development of the institutions he founded into the 20th century.

"We are here to forthrightly look at the kinds of founding stories, the myths, the half and partial truths, that undergird our institution as they undergird so many American institutions, and to bring a lens and the light of historical research to those questions … to really pave the way to at least the possibility of a different kind of future, a most just future," Jones said. "We research that history for history's sake because we love that work, but we also do it to contribute to a much broader reckoning."

Posted in University News, Politics+Society