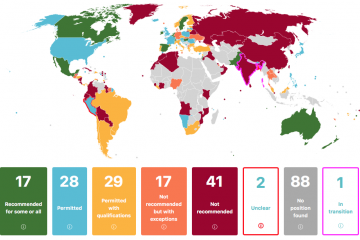

As several countries including the United States move forward with booster programs for COVID-19 vaccines, the World Health Organization continues to issue firm rebukes of such policies, pointing to glaring global inequities in vaccine access.

Just last week, WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus urged countries to halt plans for booster shots for their general populations until 2022. "I will not stay silent when companies and countries that control the global supply of vaccines think the world's poor should be satisfied with leftovers," Tedros said at a Sept. 8 news conference.

Those statements follow the WHO chief's earlier call for holding back all COVID-19 boosters until all countries can vaccinate at least 10% of their population, and an Aug. 10 WHO document pointing to "limited and inconclusive evidence" on the need for boosters as well as the danger of exacerbating inequities.

In the U.S., the Biden administration has announced its intent to offer a third booster shot to the country's residents eight months after their initial vaccination series—a contentious plan Food and Drug Administration advisers will deliberate Friday, following a published review from two departing FDA regulators questioning the imminent need for booster shots. According to remarks from White House press secretary Jen Psaki, the U.S. has donated about 140 million vaccine doses to over 90 countries, more than all other countries combined.

With its booster plans, the U.S. joins a number of countries including Israel, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom that have already announced or begun offering such programs amid the surge of the delta variant.

For insight on the ethical stakes at play, The Hub turned to Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Faden serves on a working group of experts advising the WHO on COVID-19 vaccination policy.

How can the concept of booster shots be approached from a moral standpoint?

We can start with the idea that human rights—including the right to essential vaccines and medicines—are universal and belong to each of us, regardless of where we live. Yet we also understand that the first line of protection, the first guarantor of human rights, is the nation state. Some degree of partiality toward one's own residents is appropriate for a country's political leaders to take. Residents expect that. But there is no defensible moral stance I'm aware of, no moral theory, no line of justification, that could argue that this partiality is limitless—that any country should advance the interests of its own citizens no matter the consequences for other people in the world, no matter the stakes for the entire world.

This imbalance between the partiality of nations versus the goals of global justice has defined the entire COVID-19 tragedy. Booster shots are just the latest issue in the unsavory implications of vaccine nationalism.

Globally, it's impossible to not describe the current situation as an ethical disaster. If current projections are credible, it does look like vaccine supply will be picking up significantly toward the end of this year and into 2022. There's a lot that could be accomplished in the next several months, until that happens. There's a lot that could be done with the hundreds of millions, if not billions, of doses that will essentially be removed from the global market with large wealthy countries going for boosters for everybody in their population.

Does the basic rationale for booster programs hold up right now?

Let's acknowledge that there's tremendous pressure for policymakers to act preemptively, to get out in front of the evidence in the pandemic. But a lot of policy questions right now still require data to be answered, and continued discussion. For example, what is the objective of a booster program? Is it to maintain the same level of protection that was secured in the initial primary doses of vaccines? For the entire population? And protection against what?

In the U.S., the vaccines we're using offer extraordinarily high levels of protection against severe disease and death, higher than anyone expected or hoped for. But is our goal to keep everybody in our country at these high levels of protection we never anticipated, when so many people in other countries are completely unprotected?

Are there cases when booster shots might be justified in the near term, for example for high-risk patients?

More limited policies may be justifiable to protect those most vulnerable to serious disease and death, like the immunocompromised and our oldest groups. We want to offer them protection against the most severe outcomes when that is realistically possible.

In countries that already have vaccination programs, these groups were among the first to be vaccinated, so they're the furthest out from their primary doses while we're dealing with the delta variant. The data are not yet clear, but suggest some waning protection over time. And for certain categories, such as the severely immunocompromised, it's possible the data may tell us eventually that three doses rather than two should be their appropriate primary vaccine regimen, for baseline protection.

But even if we serve our most vulnerable, we could hold off on boosters for the rest of the population until we see better evidence.

What might be a reasonable course of action for the U.S. to take right now?

It would be unreasonable for the U.S. to implement the same booster program that Israel is following. The pragmatic reality is that Israel is a much smaller country. You could argue against Israel's course of action, but it's just not nearly as consequential as what happens in the U.S. and Europe.

Now, there is a way we can walk and chew gum at the same time. For example, if the U.S. were to address the near-term shortage of vaccines in the continent of Africa, which is in a terrible state right now—maybe we could sort of square the ethics circle. A lot of us are hoping and waiting for a big move by the U.S. soon.

Also, the announcement of boosters has already been made, but the administration has since qualified its position as contingent on rulings and recommendations from the FDA and CDC. There's still time to refine the rollout of the booster program in ways that align better with global justice and global equity obligations. A lot will turn on what the technical experts in these agencies and their advisory committees conclude. The jury is still out on what level of additional real-world protection a third shot provides, against what outcomes, for what groups of people, and against what variants. I'm hoping that, for the near term, the bottom-line policy will be no more than a very limited booster program for those at highest risk of severe disease and death.

Even if we understand and respect all of the ethical complications of a booster shot, it's likely many will want one as soon as it's available in their country. So how do we reconcile our individual decisions within the larger global framework?

This is always so hard. Surely if countries are justified in showing some partiality to their residents, so are we as individuals when it comes to our nearest and dearest. But as with nations, there are limits to what levels of partiality are appropriate. At minimum, those of us who are not at high risk of severe disease should wait and rely on the protection afforded us by our primary vaccine series. Also, as a general matter, it's best for people to follow the rules. The success of the pandemic response depends heavily on everyone following expert guidance and recommended public health policy.

And finally, I want to underscore that we just don't know yet how much added protection in the real world a third shot will provide. Don't think about getting a booster as your ticket back to July 4th. People should not be relaxing their risk mitigation behaviors if they get a third shot.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged bioethics, berman institute of bioethics, ruth faden, coronavirus, covid-19 vaccine