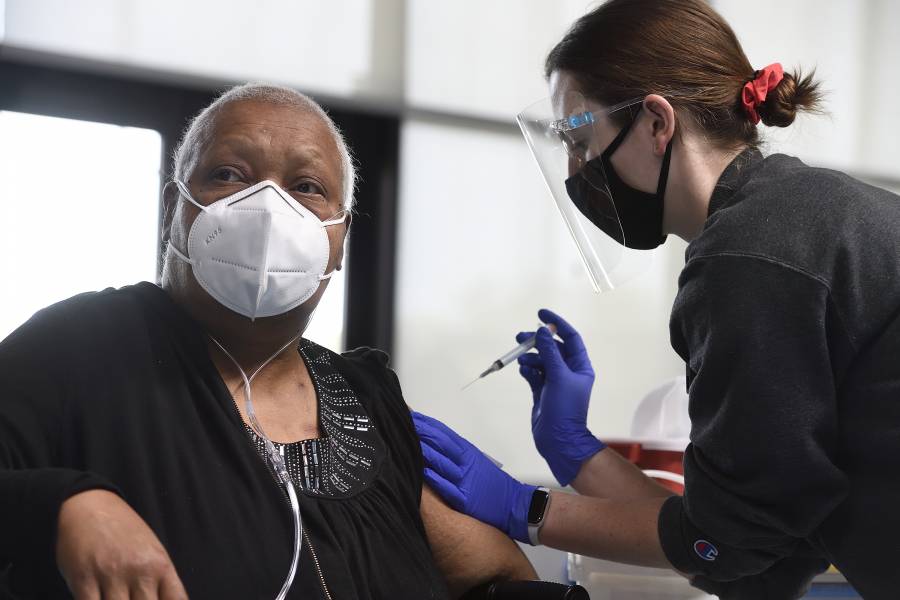

Despite substantial gains in vaccinating Americans against COVID-19, the United States must also grapple with new, sobering evidence about where the burden of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has disproportionately fallen: on minority communities.

A new study published Wednesday in The BMJ finds that, on average, U.S. life expectancy dropped 1.87 years from 2018 to 2020, when COVID-19 became the third leading cause of death in the United States. Life expectancy decreases were most significant among Black and Hispanic populations, which dropped by 3.25 and 3.88 years, respectively.

Importantly, the study indicates that COVID-19 deaths alone do not explain these life expectancy decreases. The researchers point to a constellation of systemic problems such as racial disparities in health care and a series of social and economic disruptions (such as unemployment, homelessness, and food insecurity) that have existed for decades among marginalized groups but were exacerbated by the pandemic, contributing to the dramatic declines in life expectancy seen among Black and Hispanic populations. "The large number of COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. reflects not only the country's policy choices and mishandling of the pandemic but also deeply rooted factors that have put the country at a health disadvantage for decades," the researchers write in the study.

Also see

Together, the facts paint a picture of a nation badly in need of resolving systemic racial issues and disparities and reveal an urgent need to continue vaccination efforts aimed at reaching vulnerable communities. During a media briefing Thursday, Johns Hopkins Health faculty members Lisa Cooper and Rupali Limaye, who were not involved in The BMJ study, discussed the scourge of racial disparities in health care and what it will take for vaccination efforts to reach vulnerable populations.

"We're really seeing [vaccine] hesitancy now in specific populations, and specifically within populations that have health disparities related to COVID morbidity, as well as mortality," said Limaye, an associate scientist in the division of Global Disease Epidemiology and Control in the Department of International Health at the Bloomberg School of Public Health. She is an expert in vaccine decision-making and hesitancy. "And this is really due to a lack of confidence in the vaccine, concerns about safety related to the vaccine, as well as distrust in government."

Image caption: Rupali Limaye (left) and Lisa Cooper

And while vaccine access and vaccine hesitancy may appear to be two distinct challenges, Limaye added that during the pandemic, the two have become intertwined.

"Earlier on in the pandemic, because states were requiring older individuals or all individuals to gain a vaccine appointment online, [many older adults] gave up trying to get a vaccine appointment and it essentially led to distrust in the overall health care system," Limaye said.

Limaye said there are a handful of policy strategies that could help address both vaccine access and hesitancy among vulnerable populations:

- Build trust in vaccines by selecting trusted community leaders to serve as messengers of vaccine efficacy and safety

- Lower the barriers to accessing vaccines by making them more readily available within the communities where there is need and providing vaccine options—such as the single-dose Johnson & Johnson vaccine—to populations that may have trouble following up with a second dose of the mRNA vaccine options

- Find innovative incentive programs for vaccination, whether it's food incentives or financial incentives

- Enlist employers as avenues for increasing vaccine access, whether by distributing vaccines themselves or allowing employees additional leave time for vaccination

- Ensure reliable, accurate information on vaccines is publicly available to counter misinformation and disinformation that is circulating online

Cooper, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor and pioneering researcher of health disparities, said the National Institutes of Health's Community Engagement Alliance Against COVID-19 Disparities, for which she is a steering committee member, has enacted similar strategies at sites across the U.S. to great success.

"Efforts to boost vaccine rates are still ongoing and are very strong, particularly in communities of color," said Cooper, whose new book, Why Are Health Disparities Everyone's Problem?, will be published by JHU Press June 29. "I think there may be places around the country where efforts have declined, but for the most part, in [communities where inequity is high], we're really still seeing a lot of efforts being made, fortunately. Because we do need them."

As more data on the impact of the coronavirus pandemic become available, Cooper said she is confident the evidence will serve as an alarm for policymakers and citizens alike about the importance of addressing health and racial inequities in the United States.

"Health inequities actually increase costs to our entire society," Cooper said. "They result in loss of productivity and competitiveness on an economic level; they result in community disharmony, stress, and civic unrest; [and they cause] a huge burden of human suffering."

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged health disparities, lisa cooper, race, coronavirus, covid-19 vaccine