- Name

- Kait Howard

- kehoward@jhu.edu

- Cell phone

- 443-301-7993

Scientists studying a special kind of semimetals have found a material with an unusually pristine nature that could be crucial for developing powerful new quantum technologies and discovering new phases of matter.

In an open access paper published in Science Advances, Johns Hopkins physicists and colleagues at Rice University, the Vienna University of Technology (also know as TU Wien), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology present experimental evidence of naturally occurring quantum criticality in a material.

Criticality is the point at which a material hovers between two phases—like the slushy transition between water and ice—without ever settling. Useful materials often exploit this point. For example, air conditioners use compressors to change refrigerant from gas to liquid, and the "liquid crystals" of a commonplace liquid crystal display or LCD screen are situated at a transition between liquid and solid, enabling precise control of their optical properties.

Scientists believe that the quantum version of criticality where a phase change is driven by quantum fluctuations could offer a springboard for discovering entirely new forms of matter and for developing disruptive technologies in the quantum realm. But reaching quantum criticality is difficult, with scientists usually having to resort to pressure or a magnetic field to force the material's phase change temperature lower and lower, where quantum fluctuations can take over.

"Getting close to this point is usually extremely tricky, and you're never entirely sure that your material would make it to the true quantum critical point," said Wesley Fuhrman, a lead author of the paper who worked on the project as a graduate student at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Quantum Matter. "Imagine a dartboard where the bullseye gets smaller and smaller as you lower the temperature."

The team studied a semimetal made at TU Wien from one part cerium, four parts ruthenium, and six parts tin, called CeRu4Sn6. After initial experiments at TU Wien, Fuhrman and Johns Hopkins physicist Collin Broholm probed the quantum critical fluctuations in CeRu4Sn6 using a beam of neutrons at the MACS spectrometer of the NIST Center for Neutron Research. They then brought in Qimiao Si of Rice University to help interpret the results.

What the team discovered is groundbreaking, they say. The single crystalline material CeRu4Sn6 appears to be naturally quantum critical without any external influences.

"In our case, CeRu4Sn6 seems to be at the quantum critical point without any of that mucking around—a pristine quantum criticality where the dart always hits the bullseye," said Fuhrman, adding that the future of quantum technology will rely on the ability to manipulate quantum states. "A material at a quantum critical point is ideally suited for manipulation, being at the precipice of multiple phases."

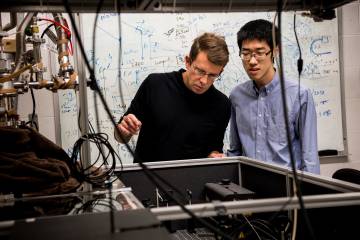

Image caption: Collin Broholm and Jose Rodriguez-Rivera during construction of a sensitive new spectrometer

Image credit: Yiming Qiu, NIST Center for Neutron Research

Quantum technology is one of the fastest-moving fields in physics and engineering, with the potential to create more secure communications, refine medical imaging, discover new lifesaving drugs, and much more. Perhaps the ultimate quantum technology, quantum computers, rely on quantum bits, or "qubits," to store information, but currently it is challenging to access, maintain, and manipulate qubits' quantum states.

More study is needed, but the researchers hope that CeRu4Sn6 could provide a design template for exploring a rich new class of quantum materials. "There's no reason to believe this is the only material where this happens," said Broholm, who directs the Institute of Quantum Matter.

In order to be realized, quantum technologies like quantum computers will require a whole host of quantum materials to make them work, Furhman explains. "A car is much more than just combustion in a cylinder. To get quantum technology rolling, we need quantum refrigerators, quantum sensors, as well as the qubits at the heart of quantum computers," he said.

For Fuhrman, the study, along with the rest of the work that's coming out of IQM, is exciting because of its potential applications. "IQM is looking at how quantum mechanics becomes tangible," he said. "You can hold these materials. And that's one of the amazing things to me about working in this domain: quantum mechanics is the physics of the ultra-small, ultra-cold, but we're pushing it to a scale that's more human."

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged physics and astronomy, quantum physics, collin broholm