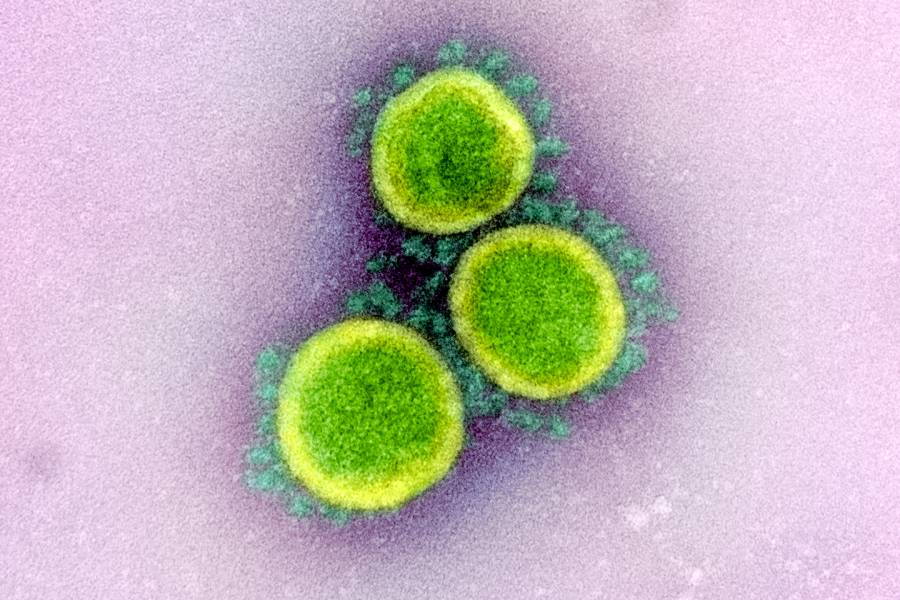

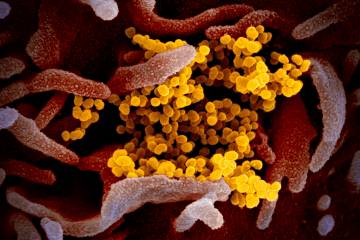

According to a recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can live in the air and on surfaces between several hours and several days. The study found that the virus is viable for up to 72 hours on plastics, 48 hours on stainless steel, 24 hours on cardboard, and 4 hours on copper. It is also detectable in the air for three hours.

Carolyn Machamer, a professor of cell biology whose lab at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine has studied the basic biology of coronaviruses for years, joined Johns Hopkins MPH/MBA candidate Samuel Volkin for a brief discussion of these findings and what they mean for efforts to protect against spread of the virus. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Volkin: According to this report, it sounds like the COVID-19 virus is potentially living on surfaces for days. How worried should we be about our risk of becoming infected simply by touching something an infected person was in contact with days ago?

Machamer: What's getting a lot of press and is presented out of context is that the virus can last on plastic for 72 hours—which sounds really scary. But what's more important is the amount of the virus that remains. It's less than 0.1% of the starting virus material. Infection is theoretically possible but unlikely at the levels remaining after a few days. People need to know this.

While the New England Journal of Medicine study found that the COVID virus can be detected in the air for 3 hours, in nature, respiratory droplets sink to the ground faster than the aerosols produced in this study. The experimental aerosols used in labs are smaller than what comes out of a cough or sneeze, so they remain in the air at face-level longer than heavier particles would in nature.

What is the best way I can protect myself, knowing that the virus that causes COVID-19 lives on surfaces?

You are more likely to catch the infection through the air if you are next to someone infected than off of a surface. Cleaning surfaces with disinfectant or soap is very effective because once the oily surface coat of the virus is disabled, there is no way the virus can infect a host cell. However, there cannot be an overabundance of caution. Nothing like this has ever happened before.

The CDC guidelines on how to protect yourself include:

- Clean and disinfect surfaces that many people come in contact with. These include tables, doorknobs, light switches, countertops, handles, desks, phones, keyboards, toilets, faucets, and sinks. Avoid touching high-contact surfaces in public.

- Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds immediately when you return home from a public place such as the bank or grocery store.

- When in a public space, put a distance of six feet between yourself and others.

- Most importantly, stay home if you are sick and contact your doctor.

There has been speculation that once the summer season arrives and the weather warms up, the virus won't survive, but we don't yet know if that is true. Does the weather or indoor temperature affect the survival of the COVID-19 virus on surfaces?

There is no evidence one way or the other. The virus's viability in exposure to heat or cold has not been studied. But it does bear pointing out that the New England Journal of Medicine study was performed at about room temperature, 21-23 degrees Celsius.

How does the virus that causes COVID-19 compare with other coronaviruses, and why are we seeing so many more cases?

SARS-CoV-2 behaves like a typical respiratory coronavirus in the basic mechanisms of infection and replication. But several mutations allow it to bind tighter to its host receptor and increase its transmissibility, which is thought to make it more infectious.

The New England Journal of Medicine study suggests that the stability of SARS-CoV-2 is very similar to that of SARS-CoV1, the virus that caused the 2002-2003 SARS global outbreak. But, researchers believe people can carry high viral loads of the SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract without recognizing any symptoms, allowing them to shed and transmit the virus while asymptomatic.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged q+a, cell biology, coronavirus