It's among the most evocative scenes in musical history: an unrelenting Ludwig van Beethoven, increasingly deaf, hammering away at the lower registers of his piano, determined to compose music despite losing his ability to hear higher frequencies. Although a long-celebrated story of perseverance, the complications of his disability forced Beethoven into an early retirement from his conducting career and plunged him into a persistent depression.

But what if, rather than struggling as Beethoven did, 21st-century musicians with disabilities could be provided with the accommodations and new technologies that make traditional musical performance and education within reach? This past weekend at the Peabody Institute of Johns Hopkins University, a small group of students worked tirelessly within a 24-hour span to build devices, design instruments, and develop software that address a broad range of issues relating to accessibility in music, performance, and music education.

Hunkered down in corners of the Arthur Friedheim Music Library on the Peabody campus in Baltimore's Mount Vernon neighborhood, participants worked Friday night and into Saturday to develop their hacks, which would be assessed by a panel of judges Saturday afternoon and awarded cash prizes.

"We have a long tradition of really serious study of music here at Peabody," says Kathleen DeLaurenti, head librarian at Friedheim and lead organizer of PeabodyHacks. "In the conservatory setting, there can be a very prescribed path that serious musicians follow for their careers. So I think a lot about how important it is to provide opportunities like this, for students to dip a toe into other interests and experiment more to see what's out there for them."

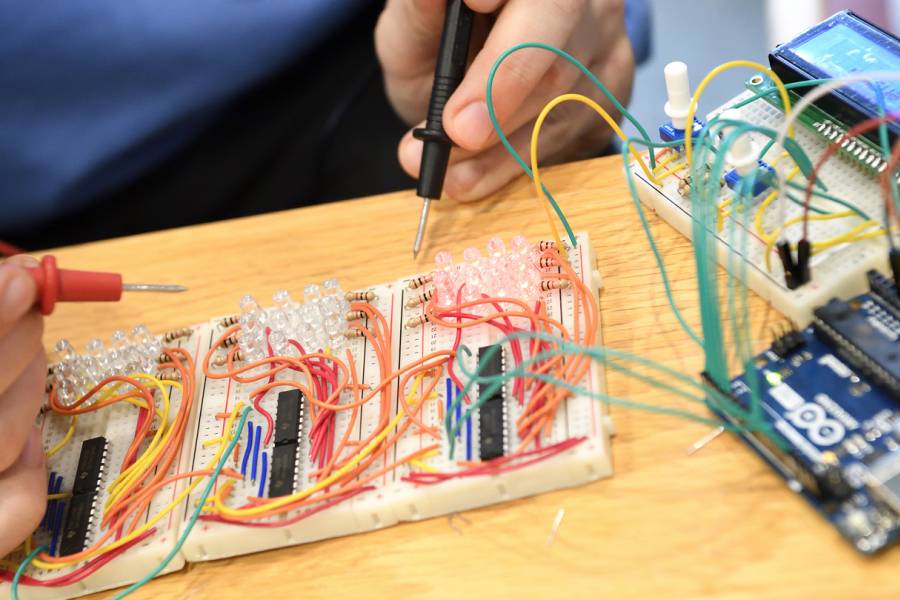

Image caption: Jacob Young (in foreground) and Collin Champagne troubleshoot their device, which aims to turn keyboard inputs into Braille for visually impaired composers

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Hackers Collin Champagne and Jacob Young barely broke for meals let alone sleep while they developed a device that would make it easier for visually impaired composers to write and read music. By Saturday afternoon, their prototype was ready for troubleshooting, and they obsessed over the software and hardware of their device, toggling wires and reconfiguring code to make it work.

Their device uses basic circuitry kits provided by hackathon organizers and an Arduino microcontroller that powers and controls a set of LED lights configured into Braille cells—a six-dot matrix that, when raised in specific patterns, corresponds with letters, numbers, or figures in the Braille alphabet. Their proof-of-concept device uses LEDs to represent Braille musical notation, and with the right tools, Champagne and Young say their device could be reconfigured to become a tactile Braille display device—similar to the pneumatic Braille e-reader displays developed at the University of Michigan—that would allow a composer to read back their work.

"People without vision loss can have all of their musical notation exportable in PDF form, but if you're blind you obviously can't do that," says Young, a first-year PhD student in computer engineering at the University of Maryland. "So this system allows inputs from different instruments to be converted into Braille cells. Ideally, we'd build something with little actuators within the cell that pop out and form the Braille so people could read, but we don't have the tools or the time yet."

Despite meeting for the first time Friday afternoon, Young and Champagne quickly formed a bond over their shared interest in engineering and their mission to develop a device that supports accessibility in music.

"There are a lot of barriers to studying and performing music, especially in the classical music world," says Champagne, a second-year graduate student studying acoustics and vocal performance at Peabody. "There are socioeconomic barriers, so if you come from an underserved community you might not have access to training. Music also often requires athleticism, so there are physical barriers. We discovered that there aren't a lot of resources out there for visually impaired people, especially for digital composition, which makes writing music so much easier."

Added Young, "It's not difficult to make a device like this, someone just has to do it."

Their efforts paid off—the duo took home first place and a $2,000 prize in the hacking category.

Their design is available online for anyone to use and build on. Part of the hackathon's mission is to support open access—meaning participants were invited to share all device designs and schematics openly and freely online so that others can expand on their ideas.

Image caption: The hackathon also held pop-up performances by students enrolled in the Peabody dance and computer music programs. Left, Chase Benjamin, Rush Johnston, and Rebecca Lee perform "\dis\connected." Right, Rush Johnston and Scott Li dance while holding Nintendo Wii remotes, which have been programmed to create expressive sounds based on movement.

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

This was the second year that John Reynolds, a junior musical education major who plays jazz saxophone, participated in PeabodyHacks. This year, he developed an interactive metronome that helps address issues of "beat deafness," a rhythm disorder marked by an inability to match a beat with a physical action like clapping. In Reynolds' design, users must perform an action in time to a beat within a game. His approach, titled Zombeat and inspired by the game Mother 3, helps users improve their rhythm in a fun and personal learning environment, as opposed to group or individual music lessons that can be costly or distracting, Reynolds says. An added bonus is the ability to change the difficulty settings, allowing users to train themselves with increasing or decreasing strictness.

Reynolds shared a third-place prize and $1,000 with another winning game design. But his efforts aligned with a personal philosophical drive.

"Technology is just one tool we can use to really emphasize the philosophy that everyone deserves an education," Reynolds says. "I follow the philosophy of psychologist Jerome Bruner who said anyone can learn anything if given enough time. Yes, there are some people who have difficulty keeping a steady pulse, but I would never want to give up on anyone and say, 'Oh, you can't learn this.'"

Second place in the hacking category went to a team of graduate students in the Department of Computer Science at the Whiting School of Engineering. Dylan Lewis, Winston Wu, and Ankur Kejriwal, who are all amateur musicians, created software that simplifies complex sheet music for beginners. The third-place prize was shared by Adam Orla-Bukowksi, whose "Ribbit" software challenges players to memorize and perform musical patterns in order to advance in the game.

Jacquelyn Deshchidn and Miranda Brugman, both graduate students studying vocal performance, took home the Innovative Instrument prize worth $1,000 for their homemade synthesizer that uses proximity sensors and loop pedals to create sounds based on voice and body movement.

Organizers included programming specifically designed for young Peabody Preparatory students, who, DeLaurenti says, are eager for opportunities to explore different ways of learning and making music and want to work alongside older musicians. During a workshop held Saturday morning, preparatory students took part in an interactive workshop about DIY instruments led by musician and educator Bonnie Jones.

"We don't currently offer electronic music classes at Peabody Preparatory, and there's some interest in seeing if this is an area where students are excited and want to learn more," DeLaurenti says. "We had a 15-student limit for this workshop, and it filled up in a day. So I think it's a really promising avenue for exploration."

The first Peabody hackathon, held last year, was funded by a Johns Hopkins Digital Education and Learning Technology Acceleration, or DELTA, grant, which supports innovative uses of digital technologies to enhance education. This year, the Conservatory independently funded the program and opened it to any student enrolled in a college with a campus in Baltimore City.

"We wanted to start locally and build bridges across Johns Hopkins between our musicians who are working with technology and our engineers who work with music," DeLaurenti says. "We used the DELTA grant as sort of an incubator to see if we could get collaboration going across campuses. This year, we wanted to open it up to other universities and see who might come."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Student Life

Tagged computer science, peabody conservatory, peabody-composition, hackathon, peabody preparatory