On Nov. 29, 1944, scores of Johns Hopkins surgeons and medical students crammed into the two-level observation gallery overlooking the Halsted clinic operating room theater. For the next four and a half hours, they watched as surgeons performed the first "blue baby" operation on a tiny child named Eileen Saxon. From behind, natural light filtered in from two large windows, bolstering the operating room's lamp light, as it did in a subsequent surgery shown above.

The frail 18-month-old, who weighed only 9 pounds, had a heart condition that was deteriorating fast. Every part of her body was blue—a sign that her ailing heart was preventing ample blood from reaching the lungs to provide enough oxygen to the rest of her body. The condition, known as Tetralogy of Fallot, is deadly.

As chronicled in Leading the Way: A History of Johns Hopkins Medicine by Neil A. Grauer, the team attending to the baby was led by Alfred Blalock, a 1922 Johns Hopkins School of Medicine graduate. He'd been a surgeon and researcher at Vanderbilt University until returning to Johns Hopkins in 1941 as the hospital's chief surgeon. Standing behind Blalock on a step stool was his indispensable technician, Vivien Thomas.

Assisting Blalock were chief surgical resident William Longmire, nurse Charlotte Mitchell, and surgical intern Denton Cooley, who would become one of the world's premier cardiac surgeons. Looking on was pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig, who, with Blalock, invented the shunt that would correct the heart defect.

Image caption:WARNING: This video depicts Alfred Blalock implanting a shunt into a heart. It contains graphic images of a surgical procedure; viewer discretion is advised.

Already renowned for his research on surgical shock when he came to Johns Hopkins, Blalock began advancing his blue baby heart studies, aided by Taussig and Thomas. Blalock refused to accept the then-prevailing opinion that cardiac surgery techniques had reached their limit to safely repair complex heart deformities.

Until the day of that milestone blue baby operation, most infants and children with the heart defect died. This surgery was deemed a success, thanks to implantation of the new shunt, which increased blood flow, allowing enough of it to pass through the lungs and pick up more oxygen.

The story behind the surgery was the subject of the 2004 HBO movie Something the Lord Made, filmed at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

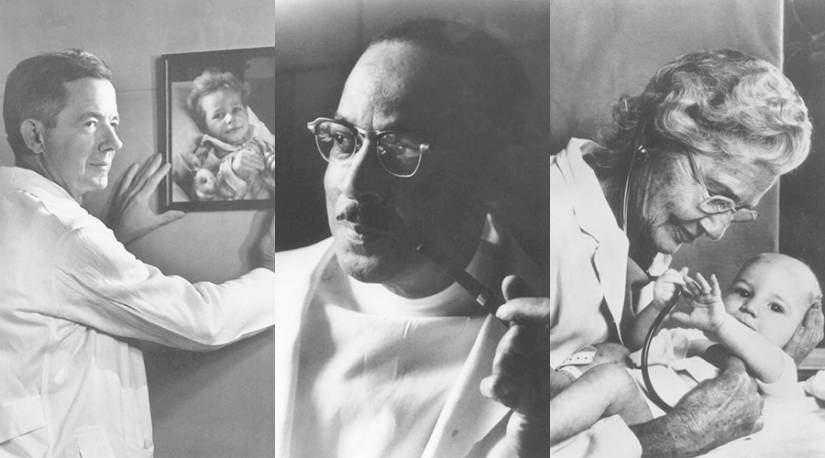

Image caption: From left: Alfred Blalock, Vivien Thomas, and Helen Taussig

Image credit: Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives

Michael Edenburn, blue baby No. 44, can attest to the technique's effectiveness. The 76-year-old businessman recently returned to Johns Hopkins and reported: "My doctors tell me my blood chemistry is that of a very healthy 25-year-old."

Along with saving the lives of thousands of children, the groundbreaking procedure is credited with creating and transforming the field of modern cardiac surgery.

William "Bill" Baumgartner, retired chief of cardiac surgery and creator of the Johns Hopkins heart and heart-lung transplant programs and surgical treatments for heart failure, says the impact has been gratifying.

"The story of Blalock, Taussig, and Thomas is one of the most compelling stories in medicine," he says. "The successful performance of the blue baby operation placed Johns Hopkins on the global map and opened the door for cardiac surgery, nationally and internationally. Patients flocked to Johns Hopkins from all over the United States and the world."

In January 2020, the Blalock–Taussig–Thomas Pediatric and Congenital Heart Center will open. The director of the center—a collaboration among pediatric cardiology, pediatric cardiac surgery, and pediatric anesthesiology—will be pediatric cardiac surgeon Bret Mettler, currently an assistant professor in the Division of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

This article originally appeared in The Dome.

Posted in Health, University News

Tagged johns hopkins hospital, cardiovascular health, johns hopkins history