- Name

- Amy Mone

- amone@jhmi.edu

- Office phone

- 410-614-2915

A new study from researchers at Johns Hopkins shows that an immunotherapy drug appears to treat Merkel cell carcinoma, a rare but aggressive form of skin cancer, more effectively and with better survival rates than does conventional chemotherapy.

The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, supported the recent move by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to accelerate approval of pembrolizumab, marketed as Keytruda, as a first-line immunotherapy treatment for adult and pediatric patients with advanced Merkel cell carcinoma.

The study, co-led by Suzanne Topalian, associate director of the Bloomberg–Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, is the longest observation to date of Merkel cell carcinoma patients treated with any anti-PD-1 immunotherapy drug used in the first line.

In the 50-patient study, more than half of the patients (28, or 56 percent) had long-lasting responses to the treatment, 12 of whom (24 percent) experienced a complete disappearance of their tumors. Nearly 70 percent of patients in this study were alive two years after starting treatment.

"This is the earliest trial of immunotherapy as a front-line therapy for Merkel cell carcinoma, and it was shown to be more effective than what would be expected from traditional therapies, like chemotherapy," says Topalian. "Immunotherapy provides an effective treatment for patients with Merkel cell carcinoma who before had few options. Immunotherapy is unique in cancer treatment, because it does not directly target cancer cells but rather removes constraints on the immune system's natural ability to find and destroy cancer cells."

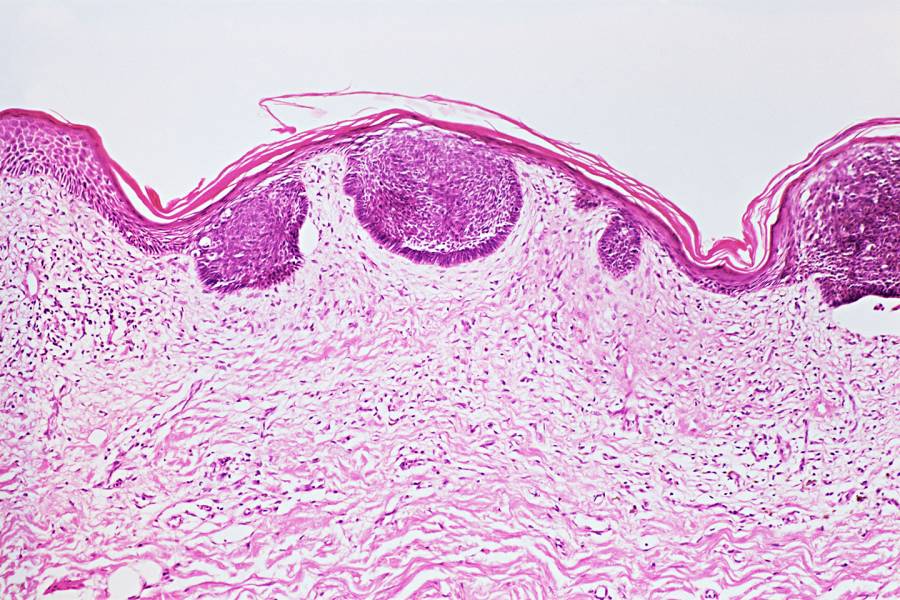

The National Institutes of Health classifies Merkel cell carcinoma as an "orphan disease," as it is diagnosed in fewer than 2,000 people annually in the U.S. It typically occurs in older people and in those who have suppressed immune systems. About 80 percent of Merkel cell carcinomas are caused by a virus called the Merkel cell polyomavirus. The remaining cases are attributed to ultraviolet light exposure and other unknown factors.

In the study, treatment with pembrolizumab worked well against both virus-positive and virus-negative Merkel cell carcinomas, resulting in high response rates and durable progression-free survival in both forms of the disease. The findings also showed that tumors expressing a PD-1-related protein called PD-L1 tended to respond longer to treatment, although patients whose tumors did not express PD-L1 also responded.

"These findings could be a precursor to developing more effective treatments for other virus-related cancers, which account for about 20 percent of cancers worldwide," says William Sharfman, a professor of cancer immunology and melanoma research who served on the research team.

The non-virus-related subtype is characterized by high numbers of genetic mutations in cancer cells, which has also been shown by the Bloomberg–Kimmel Institute group to be a biomarker of response in various cancers to checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab.

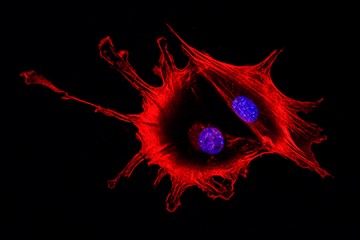

Pembrolizumab works against Merkel cell carcinoma by blocking PD-1, a molecule on the surface of immune cells that regulates immune responses, turning them on and off. Cancer cells often manipulate PD-1 to send a "stop" signal to the immune system. Blocking that signal with a checkpoint inhibitor, such as pembrolizumab, initiates a "go" signal, sending immune cells to attack cancer cells. A protein on the surface of cancer cells, called PD-L1, is one mechanism cancer cells use to manipulate PD-1 and disrupt the immune response.

"Under the microscope, PD-L1 looks like an armor around the cancer cell," says Janis Taube, an associate professor of oncology, dermatology and pathology. "Pembrolizumab interrupts PD-1 signaling by blocking the communication between PD-1 and PD-L1, removing the stop signal and re-engaging the immune system to go after cancer cells."

Patients in the study received the immune checkpoint blocking drug pembrolizumab intravenously every three weeks for up to two years. During this time, the status of their cancer was monitored periodically with imaging scans. Overall, most patients tolerated the treatment well. However, 28 percent of patients experienced serious side effects, including one treatment-associated death.

Posted in Health

Tagged cancer, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, bloomberg-kimmel institute