"If it weren't for Johns Hopkins, I'd have been a postal clerk," Russell Baker once said to me.

That actually wasn't far from the truth.

After graduating from Baltimore City College in 1941, Russ had gotten into Hopkins on a scholarship. In 1943, however, he dropped out to join the Navy during World War II. Inspired by Hollywood films showing heroic, goggle-wearing pilots, perhaps with a scarf flapping behind them in the wind, he enlisted in the air corps. "I wanted to die for my country," he'd say with just the right touch of wry irony.

He never got out of the United States—although he did learn to fly. (Sort of.)

After the war, he returned home. His scholarship gone, he went to work in the post office. Then he learned about the G.I. Bill and happily took advantage of it to end his postal clerk career and go back to Hopkins. Like any alumnus, he occasionally would grumble about something at the old alma mater of which he disapproved, but his pride in having attended Hopkins was undiminished and palpable. Once, when he was driving me around Morrisonville, the Virginia hamlet in which he was born, we went by the site where his grammar school had stood. He pointed to it and said, "It's from there that I began on the road to Johns Hopkins."

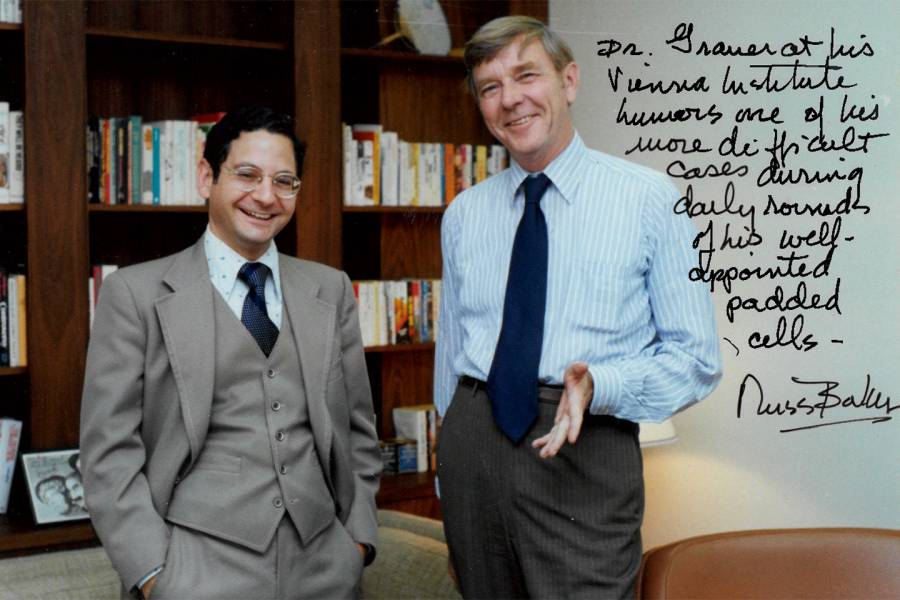

I met Russell Baker in 1968. I had seen him speak at Hopkins a few years earlier, knew he was an alumnus who'd willingly show up to talk to student journalists, and having long admired his Observer column in The New York Times, I wanted to seek his advice on pursuing journalism as a career.

I called his office at the Times' Washington bureau, asked if I could come discuss my post-graduate options. With the unfailingly sympathetic generosity that I came to learn was central to his being, he invited me down.

We would remain friends for the next 50 years—exchanging letters, inscribed books, getting together for lunch, and commiserating on the state of the nation, the world, ourselves.

Despite our 22-year age difference and the identical lapse between his graduation in 1947 and mine in 1969, we found that some aspects of Johns Hopkins in the 1940s and the 1960s really hadn't changed. We even had taken a few courses from the same professors—since ones who were in mid-career when Russ was at Hopkins still were on campus during their pedagogical twilight when I was a student.

We both had taken G. Wilson Shaffer's course in abnormal psychology. So had my father when he was a student at Hopkins from 1932 to 1936. And like my father, Russ and I both had taken Frederick C. Lane's course in occidental civilization.

Russ told me that it was Dr. Lane who offered a critique of a term paper or exam he had written that stayed with him for the rest of his life: "You find it too easy to be smart."

Humor was one thing; flippancy another.

Great care had to be taken, no matter what you were writing, whether it was meant to be serious or funny. Writing was hard work. In July 1980, when Russ was working on what would become his Pulitzer Prize-winning autobiography, Growing Up, and I was working on what would be my first book, Wits & Sages (profiles and caricatures of syndicated columnists, Russ among them), he wrote me: "I hope your book is going easier than mine, which feels dead in the water at present. Summer is a hard time to toil at such dim work." He later told me—perhaps hyperbolically—that he knew his book was in trouble when he began reading a draft and he fell asleep.

Two years later, after Growing Up had been published and received an avalanche of well-deserved acclaim, I still was working on Wits & Sages. Sending Russ my copy of Growing Up to be inscribed, I mentioned in my cover letter that I was about to embark on the fourth re-write of a chapter. He replied: "As for your forthcoming 4th or 5th rewrites, remember: You have to write it seven times to make it sound like you only wrote it once."

Dr. Lane's influence had endured—for both of us.

When we got together for lunch, Russ always wanted news about Hopkins—whether I thought it still was as good as it had been during our undergraduate years. He doubted it, but had no nostalgic illusions about the good-old-days. The course catalog listed great courses that never seemed to be given, he complained.

"Charles Singleton, the Renaissance scholar, always was away on sabbatical or something. I never got to take any course with him."

I felt a tad guilty—but not much—to tell Russ I'd been able to take two courses with Singleton.

Russ also enjoyed making fun of Hopkins' reputation as a place where students worked hard. In 1993, when Inside Edge, a magazine for college students, published a list rating 300 colleges and universities as those that were the most-fun and the least-fun, he wrote a column full of mock umbrage that Hopkins had not been listed as the "least-fun" school. It ranked only 297. The University of Chicago was 300.

"The assertion that the University of Chicago is less fun than Hopkins strikes me as outrageous," he wrote. He listed all the un-fun things at Hopkins—including lacrosse, which he considered an obscure sport; the incomprehensibility of some professors; and a lack of "school spirit."

Yet Hopkins' "heavy concentration on the chalky pursuit of academic splendor had to leave you with some compensating satisfaction for the funlessness, didn't it? So we got tremendous fun out of our contempt for having fun."

"The Hopkins spirit is still in my marrow," Russ declared—and he demonstrated it for decades by working tirelessly to make sure we had fun reading what he wrote.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

Tagged in memoriam