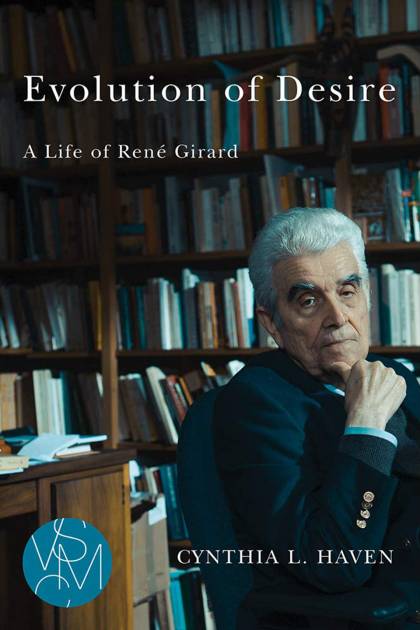

René Girard, the late French literary theorist and philosopher of social sciences, probably isn't the first intellectual who comes to mind when wrestling with the political tumult of 2018. But as cultural journalist Cynthia Haven notes in Evolution of Desire, her recent Girard biography, he very well might be the thinker we need.

In a series of books published in the 1960s and '70s, Girard analyzed literature to unlock what makes humans tick, why they do the things they do, and why they scapegoat the people they do. And Haven, who blogs about literature at Stanford University's The Book Haven, writes that the explanatory power of these ideas "roams from international politics to the memes on the daily Twitter feed."

Girard wrote and published many of the books that form the core of his thinking during his time at Johns Hopkins University. He spent nearly 15 years at the university's Homewood campus, arriving as an associate professor of French in 1957. He left in 1968 for the State University of New York and came back in 1976 to join the faculty of the Humanities Center (known today as the Department of Comparative Thought and Literature) before moving on to Stanford in 1981, where he would remain until his death in 2015.

During his time at Hopkins, Girard published his first book, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel: Self and Other in Literary Structure—first in French, and then in English translation by the Johns Hopkins Press in 1965—and worked on what would become his breakthrough text, Violence and the Sacred, which Hopkins Press published in English translation in 1977. He also helped organize, alongside now Professor Emeritus Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato, "The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man" conference that imported French literary theory to America.

Girard's Hopkins career, which Haven calls "one of the catalytic periods of his life," occupies the middle section of Evolution of Desire. The Hub caught up with Haven, who today was named a 2018 National Endowment for the Humanities Public Scholar, via email to talk about Girard's time at Homewood, his ideas, and what makes them not only relevant today, but necessary.

Use the links below to jump to a specific question in the conversation.

- How would you describe Girard's theory to a general audience?

- What made the '60s such a fertile period for the humanities—at Hopkins and beyond?

- To what do you attribute Girard's more niche popularity in the U.S.?

- How did your personal relationship with Girard inform your understanding of his ideas?

- What effect did witnessing the Jim Crow era in the South have on Girard?

- What effect did his religious conversion have on his work?

- What qualities of art, music, literature, and theater drew Girard?

- What do you think Girard has to tell us about today?

While Evolution of Desire is written for a general reader, I imagine that general reader is probably going to have some interest in and familiarity with literary criticism. How would you describe Girard's theory of mimetic desire for a layperson, and why it has such lasting significance?

I'd start this way: We want what others want. We want it because they want it. These desires are shaped by our restless imitation of others. When the coveted goods are scarce, these desires pit us against one another—on an individual level, on a community level, and on a global scale as well. It causes divorces and it causes international wars. It causes children to fight over a five-buck toy in the sandbox.

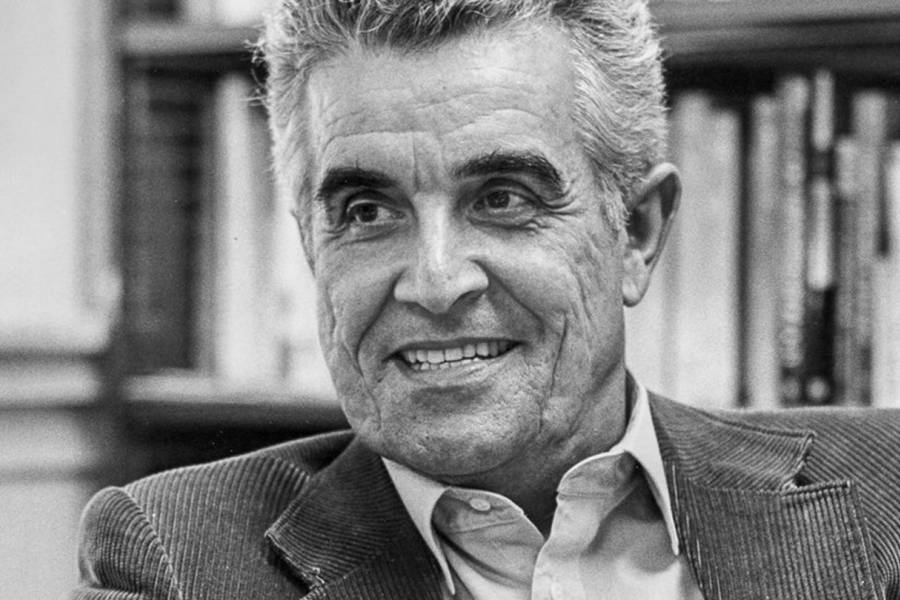

Image caption: "Talking with him was always such an adventure. Writing Evolution of Desire was an adventure, too," says Cynthia Haven.

René Girard wrote: "All desire is a desire for being." It's a phrase I use often because this imitated desire is powered by the wish to be the person who models our desire for us. We think that this person possesses metaphysical qualities we do not. We imagine the idolized individual has the power, charisma, cool, wisdom, equanimity. So we want that person's job, shirt, car, spouse. The relationship, as he wrote, is that of the relic to the saint.

The nature of desire is mysterious. René said: "Desire is not of this world. That is what Proust shows us at his best: it is in order to penetrate into another world that one desires, it is in order to be initiated into a radically foreign existence." No wonder he was such a devotee of Proust!

That passage succinctly answers the second part of your question as well. Our most fundamental longings—throughout the centuries—are addressed in his corpus. That is why it is important, and always will be important.

Girard's stint at Hopkins was a significant period for him but also for Hopkins' emerging Humanities Center and for French intellectuals in the U.S. in general. As you show in Evolution, the personalities involved contributed a great deal to the intellectual life of the times. I'm curious: what do you think made this era—at Hopkins, in the U.S.—such a fertile period for the men, as it seems to have been exclusively men, of that era?

It was a time when so many of the best professors were refugees. Certainly the humanities at Johns Hopkins benefited by taking in scholars who were fleeing war or impending war in Europe. The list includes Nathan Edelman of France, Ludwig Edelstein of Germany, and influential literary critic Leo Spitzer of Austria. At Johns Hopkins, Girard also met literary critics such as Georges Poulet and Jean Starobinski, as well as the Spanish poet Pedro Salinas. Enlightened leadership played a role at Johns Hopkins; no doubt the brand new Humanities Center did, too. It was a special moment in Johns Hopkins' history. Everyone who was there at the time felt the electricity.

And it wasn't entirely for men—although, as I note, not a single woman was on the program for the 1966 symposium. Change was already in the air, however. By the time of the conference, Girard's first graduate student, Marilyn Yalom, had already received her PhD from Johns Hopkins, a degree she earned while she was the wife of a medical intern and mother of several children. She would go on to be a leader in feminist studies and a prominent author in her own right.

I greatly enjoyed the chapter devoted to The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man symposium in 1966, and I appreciated how you accurately point out that whatever knock-off version of Derrida's ideas that persists in culture today, they're poorly understood and even more inadequately used. You point out that interest in this symposium persists more than a half-century on. Aside from being the launching pad of Derrida across America, why do you think that is?

Dick Macksey says he still gets correspondence from people who are "addicted to one or another of the players." I flinched at that because I suppose I am one of them. The Structuralist Controversy, the book of the proceedings, is a rare academic best-seller and is still in print all these years later.

Also see

That said, I'm not sure the symposium does get much attention. It's not very well-known outside rarified academic circles. America may have been ground zero for deconstruction, but most American students aren't familiar with much philosophical thought from the last 50 years. "Deconstruction" has become, in the popular culture, a lazy synonym for "analyze." The average student maybe gets a little bit of Plato's Republic or Machiavelli's The Prince. Perhaps a little Locke in political science classes. But you can easily get a bachelor's degree from a major university without much more than this. Meanwhile, our French counterparts are able to play with abstract philosophical concepts in a way we cannot. It's in their bones. They get it in high school.

That's why deconstruction could sweep America. I compare it to a smallpox epidemic, finding a population with no immunities. It's not the only case where ideas have swept over large portions of America without balance or moderation.

It's a great argument for the humanities, isn't it? When people are more grounded in philosophy, when they're conversant with the history of ideas, they can recognize intellectual fads or even frauds—think of the gurus of the 1970s—and don't mistake them for wisdom or truth. It requires a philosophical sophistication and flexibility that's not part of the STEM agenda.

I ask because though Girard was one of the symposium's co-organizers who provided a cultural bridge to French intellectuals, I kind of feel like he and his works can feel less well-known in America. To what do you attribute his, shall we say, more niche awareness? I mean, he lived in the U.S. for the majority of his adult life. And, since your book encouraged me to go back and reread some Girard, his ideas feel more direct, and his writing certainly less aggressively complex, than some of the French thinkers who have occupied rock-star status in the States.

You're right. His writing is powerful, incisive, lucid. It invites you to change your life. Not in the sense of becoming a camp-follower or a professional "Girardian," but rather encouraging awareness of how we scapegoat others, how easily we join crowds, and how we hunger for the wrong things for the wrong reasons. These are at once the lineaments of human history and the contours of our personal life stories as well. And let's not forget that his writing is great fun to read, too.

Certainly part of the reason is Americans' general disinterest in European thought, as we've discussed already. How many know the work of Michel Serres, another major French thinker?

Jean-Pierre Dupuy, yet another French intellectual largely unknown here, suggests a different reason. It's an obvious one: Girard's Christianity alienated audiences in secular France. Even in American academic circles, bringing up Christian thought can be a little like burping at dinner. I was keenly aware it would not be so if he were a practicing Muslim or Buddhist.

There's one reason he's not well-known that I tried to tackle singlehandedly: No one has tried to explain his ideas through the man himself, embedding them in his life and times. I wanted to reach readers who might not pick up a book that drills down into abstruse theory on the first page, but who would be willing to give him a hearing if the life and work were woven together in such a way to present a living man, rather than a summary of a couple of dozen books.

I also tried to situate him among his peers, not as man standing alone in an empty field. That's one reason I spent so much time discussing the 1966 conference. He was embedded in an intellectual history, and his thought paid tribute to the work of others, from Aristotle to Max Scheler's Ressentiment—and even Derrida. Girard had respect for Derrida, devotes two pages to "Plato's Pharmacy" in Violence and the Sacred.

You note in your introduction that you came to Girard and his ideas not through his works but through personal friendship. You know him. How did this personal relationship inform your understanding of his ideas?

It certainly made writing more of a tightrope act. As many have noted, the book is, in part, a memoir, and I try to make my friendship apparent—I didn't want to fake an "objective" stance. I got to know him at a certain time in his life, in a certain place, and my understanding of him is inevitably torqued accordingly.

As to how it affected my understanding of his ideas, his life was a seal on his work. I saw that he practiced what he preached and got better as he practiced. I'm a firm believer that, as the Slavic scholar Carl Proffer wrote, "Dostoevsky insisted that life teaches you things, not theories, not ideas. Look at the way people end up in life—that teaches you the truth."

One of the greatest influences in education—I say this in an era when online learning is all the rage—is to be around men and women who are not merely giants of the intellect but giants of being. Wise people who exemplify their profoundest thoughts. Mimetic models are unavoidable, but we can put ourselves under the influence of those who will transform our thinking and our lives.

In my experience, there can be a certain leeriness about literary criticism and theory because it's considered obstinately intellectual and removed from life as lived. And yet, and as I think you show in writing about Girard and his ideas, there's a wealth of the lived experience that informs intellectual labor. So I want to ask you about three examples of that in Girard's life that came to mind when reading Evolution. The first concerns Girard's understanding of the racial violence of the South during his year at Duke University in 1952–53. I get the impression from that chapter that you suspect the Jim Crow South had a marked effect on him.

How could it not have affected him? He had arrived from France only five years before and was suddenly fully immersed in the Jim Crow South for a year. That's why I spent pages explaining what it was like: For the millennial generation, this will be as alien to them as Mars. I recall what a shock it was for me traveling briefly through the South in the 1960s—and I'm an American.

René wrote about his impressions in an autobiographical fragment that I quote in Evolution of Desire. He would make passing references over the years. But he was silent about so much in his life. He once said, "I'm not concealing my biography, but I don't want to fall victim to the narcissism to which we're all inclined." That made my job a little harder.

But there's more to it than that. He and his wife, Martha, had a way of not "seeing" the faults of their friends, and not "remembering" the trauma, upheaval, and even wickedness around them. They don't gossip. They came of age well before the confessional era, remember, and a stiff upper lip policy was not confined solely to the British. They extend much forbearance and charity to their friends. Frankly, I think I'd be a much better person if I were more like them.

From the point of view of the intellectual biographer, what do you think Girard's religious conversion experiences in 1958–59 made him feel about his work? Perhaps what I'm asking comes from being raised with a hearty variety of Mexican-American mystical Catholicism, but it seems like what his conversion introduced was a need for a more complex sensitivity to moral ideas in his explorations of ethics.

I don't think it was anywhere near that intellectual. You don't "decide" to see a butterfly.

He had been writing Deceit, Desire, and the Novel, a study of several novelists whose protagonists went through an end-of-life conversion, a conversion that was not necessarily "religious" in any overt sense but seemed to involve an element of self-abandonment, self-renunciation.

To his surprise, he found that he was undergoing the same experience that he had been describing in his book, in which he said the novelists had realized that they were nothing but "a thousand lies that have accumulated over a long period, sometimes built up over an entire lifetime."

It's often said that we take things too personally. But perhaps a greater error is not taking things personally enough. Suddenly, it was personal for him. Suddenly, his own life went under the microscope. How does that change your writing? It changes nothing. And everything.

After his experience, the words on the page became real to him. He wanted to engage the authors on their own terms—his new experience had given him the evidence to do so. Whether he was working in anthropology, history, literature, myth, he began to trust that the texts were real, and trying to tell us about real events. This deep understanding became a cornerstone of his work.

We don't know exactly what happened to him, other than his words and the few remarks he made to others. We only have the clues he left us, like this one: "Conversion is a form of intelligence, of understanding."

What can you tell me of Girard's aesthetic world? I mean, I know intellectuals choose to write about the works they do because they fit into the larger ideas and theories they have, but I also think intellectuals write about works that genuinely move them in some way. What qualities of art, music, literature, theater, whatever, did Girard like? What was he drawn to? What novel or piece of music might he, say, suggest to a friend simply because he wanted to pass along its aesthetic experience?

He once said to me, "I tend to have the taste of my mother, you know, who was classical." That was about music. But art? He told me he wondered if today's art might be "a conspiracy of merchants."

I don't remember him passing along recommendations, but he certainly did communicate his enthusiasms. Way back in the late 1960s, he saw a performance of Shakespeare that led him to a passion that resulted in the only book he conceived and wrote in English, A Theater of Envy.

His tastes remained very French. At the end of his life, he told me he wanted to write a book about Countess of Ségur, who had been born Sofiya Feodorovna Rostopchina, whose father was supposed to have burned Moscow in 1812. She became the greatest writer of children's stories in the 19th century—something like 35 million, ultimately. And he also said that he was rereading Madame de Staël.

But recommendations? I can't think of anyone he would recommend more strongly than Proust. But that takes us back to that earlier quote about desire. That madeleine, the longing, the desire for beauty.

Both The Marriage of Figaro and chant have this in common: It is music that reaches beyond itself and touches the eternal, that penetration into another world "in order to be initiated into a radically foreign existence."

Finally, I know it's a bit of folly to ask such things, but as you point out in both your introduction and postscript, Girard is actually somebody who might have something to tell us about right now. He died in 2015, prior to the elections in 2016 and 2017 in Europe and the U.S. What do you think Girard has to tell us about our current time and the highly polarized world in which we currently live?

He'd tell us it's always imitative behavior. And we fight not because of our differences but our similarities. Is the world as polarized as we think? Both sides want the same thing: power and supremacy. As they fight, they come to resemble one another more and more, all the while insisting they have nothing in common. They echo and amplify one another's public accusations, campaign tactics, social media tantrums, fundraising pitches, legal actions, and even violence in their escalating tit-for-tat retaliation.

Watch as each side successively finds scapegoats on which to hang all the blame, with increasing hysteria and hyperbole. Eventually, the political leaders and the media turn toward one person, or one small group of people, on which to pin the responsibility for the conflict. The targets may not be entirely innocent, but the blame heaped upon them will be disproportionate and fantastical. The vox populi will demand their punishment, resignation, incarceration, expulsion. And when that fails to restore social harmony, they will find a new scapegoat.

René and I often discussed the news together—he was an indefatigable news-watcher. The people who were drawn to his work crossed all sorts of partisan divides, and he accepted everyone impartially.

In 2008, he pointed out to me how general anxieties in the nation would be repeatedly funneled into public duels between two people. At that time, the financial instability was creating public unease, and the media pitted Clinton and Obama against each other again and again to further inflame public opinion. It's our own cheesy reprise of Sophocles and Euripides, without the artistry.

He was always seeing something I didn't. I remember asking him for his own impressions of the financial crisis. And he pointed out that Europeans would have rushed the banks under the same circumstances, precipitating a worse crisis. He marveled at the American trust in its institutions, which allowed us to ride out national crises. He came at events from a different angle, like a visitor from another planet.

That's why talking with him was always such an adventure. Writing Evolution of Desire was an adventure, too.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged literature, humanities, q+a