On a quiet plateau in Wyman Park Dell, two Confederate leaders immortalized in metal once sat astride their horses looking toward Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus.

On Saturday, the now-empty platform where the Jackson-Lee statue formerly stood will be rededicated in honor of Harriet Tubman.

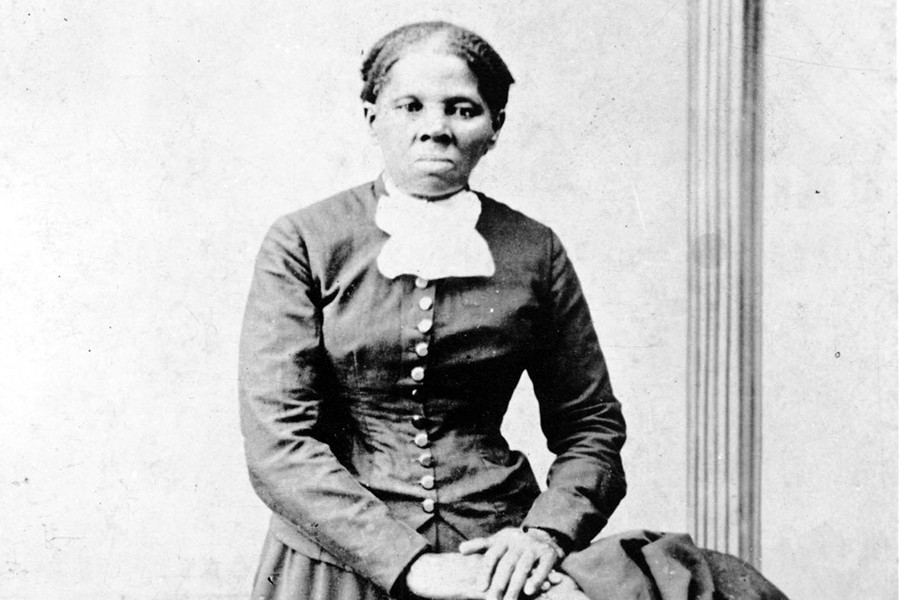

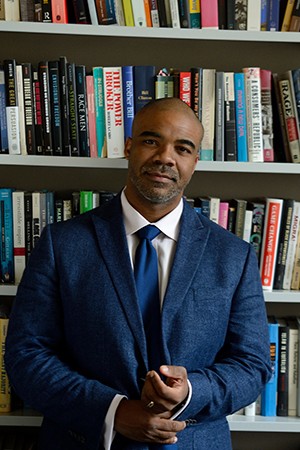

The city ordinance to rename the Wyman Park Dell plateau in honor of Tubman on the 105th anniversary of her death is a meaningful gesture, says Johns Hopkins historian N. D. B. Connolly. Too often, he says, her legacy has been diminished.

"I think sometimes we reduce her to a Black History Month fact," says Connolly, an expert in politics, capitalism, and racism. "We should try to take the fullness of her contributions into account—she is absolutely an American hero."

The Hub spoke to Connolly for insights into the life of Tubman, an American abolitionist and humanitarian born on Maryland's Eastern Shore in the 1820s whose life has become shrouded in mythology.

Who was Harriet Tubman?

Harriet Tubman is a central figure in mid-19th-century history, culture, and politics. She helped to free enslaved people as part of the Underground Railroad—a conductor of the Underground Railroad who was critical to creating and running a network of safe houses between the South and the North. But her life was a very tragic one.

Image caption: N.D.B. Connolly

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

She was a child slave, and she was constantly rented out to work in a variety of homes with cruel masters. If you can imagine the way a tenant would rent an apartment, a worker in the context of slavery could be rented out by the master, and people would often be more abusive than they would if the slaves were actually their property. For most of her childhood, Tubman suffered serious, serial instances of abuse at the hands of her various masters. She was whipped about the face and neck, she was scarred, she had bones broken, and she suffered a very severe head injury.

The early part of Tubman's life really prepares the foundation for her later heroic deeds in flouting slavery. But it's also important to note that she took to aiding runaways after failed attempts to use legal channels.

During her youth, there was an elaborate system of wages between masters, renters, and slaves, and during that process Tubman actually made a little bit of money and tried to get lawyers to keep her relatives from being sold, to keep families from being broken up. It was really only after failing to seek redress through the courts that she decided to take action into her own hands in the 1840s with spiriting people away to free lands.

I never knew about her efforts with the courts. What else do you wish more people knew about her?

Well the first thing to know about Harriet Tubman is that she really is an action hero. We have a lot of ways of thinking about the heroism of John Brown or Nat Turner, but Harriet Tubman is an action hero, too. She literally sprung people, multiple times, from bondage, sometimes the same people more than once. And if you think about the kind of rescue work that she had to do to get people out of slavery—estimates say at least 70, but some say as many as 300 people—and she never lost one en route. I mean, I know how hard it is to get my kids out the door—moving another person anywhere is a challenge! And she did this across hundreds of miles under the harshest conditions, with people constantly seeking her and wishing her death.

It's important, right off the top, to understand that she is as heroic as it gets.

Tomorrow, the Baltimore City Council will dedicate the plateau where a Confederate statue once stood in Wyman Park Dell in her honor. Why is it important to dedicate a space for reflection and a space to honor black heroes, especially in a city like Baltimore?

I think it's critical, first, to recognize that Maryland was a slave state. Rather than honoring those who defended slavery, we should honor those who fought against slavery and those who fought injustice. They fought on the side of what was morally right, even if it wasn't always legal. "Stealing" slave masters' "property"—people—was illegal. And this is really important because we have a hard time now even allowing people to challenge laws through direct action.

Image caption: The plinth where the Lee and Jackson Monument once stood has been the site of graffiti as well as protest art, including Pablo Machioli's statue, 'Madre Luz'

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

We've come to vilify a lot of protest means, even those who operate within legal channels. Anything that memorializes and immortalizes the heroism of someone like Harriet Tubman really helps to fix in place, as part of our culture, the idea that protesting immoralities, despite them being legal, remains a hallowed and necessary tradition.

Also, making the space to recognize the heroism of a black woman is critical. Black women are by every possible measure the foundation of the plantation system, of the Jim Crow labor system, and of the current inequalities relating to mass incarceration, eviction, public health—all of these things fall disproportionately on black women. Anything we can do to help to claim public space to honor and respect the contributions of black women is really important.

In addition to honoring her on March 10, in addition to having a space in Wyman Park Dell that commemorates her, I would hope that we begin to have frank and consistent conversations about what Harriet Tubman did in her life and what the analogs are for that in the present. Anything that can create much more explicit public engagement and helps bring the humanities more into our political debates is going to be necessary going forward.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged history, baltimore, civil rights, nathan connolly, women's history month