Larcia Premo keeps track of her empties—pearlescent pink, burnished bronze, clear lacquer, matte black. When she hears the telltale hollow rattle of a spray paint canister on its last aerosol breath, she makes a note on a makeshift inventory she keeps on a scrap of paper. She urges her students to get every last drop of paint—they can use as much as they want but shouldn't be wasteful with the classroom inventory.

It's the last day for students to finalize the clay and papier-mâché masks they created during Intersession, and Premo, an instructor in the Johns Hopkins Center for Visual Arts, is buzzing around advising students on paints and sealants to use. Taught for the first time this year, The Many Faces of Masks challenges students to create decorative or functional masks using an array of techniques and the supplies that Premo provides.

For Premo, teaching studio art to students on the Homewood campus is a joy and part of a journey she began when she herself was a student at Hopkins. After dropping an organic chemistry class because of an illness, she took history of art instead, sparking a change in her college and career paths that would take her from aspiring doctor to artist.

When she looks at the students in her Intersession class—with majors in biomedical engineering, political science, molecular and cellular biology, and public health studies—she's reminded of her own early experiences with art.

"I think that in general, art and science are really linked," she says. "They're both steeped in curiosity about life."

Before the class embarked on its own mask-making earlier this month, students learned about the history of masks, their cultural roles, their practical purposes, and how they affect the human psyche. A major theme Premo explored is how masks help heal emotional wounds. She shared a 2015 National Geographic article on the use of mask-making to help veterans cope with post-traumatic stress disorder.

"I think in the process of any kind of art, not just masks, if you're expressing something that might be related to trauma, it finally brings words to the surface," Premo says.

Some students created masks with personal and cultural connections, like senior Jared Mosher, a biomedical engineering major who created three decorative masks. The first two, he says, draw from ancient Japanese and Chinese traditions of displaying the faces of demons to provide protection. The final mask he made was derived from images of ancient Colombian deities and was sculpted as a gift.

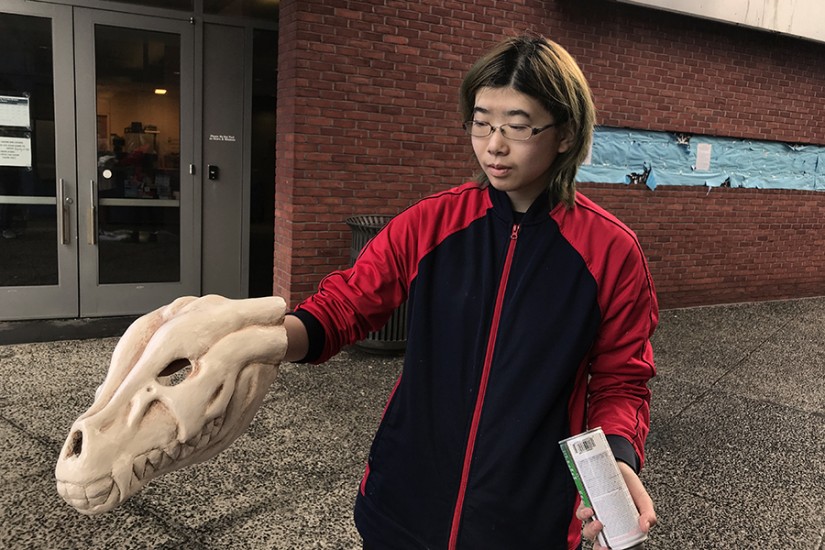

Other students created masks with more practical applications. Alex Yu, a junior public health major, made a wearable skull mask inspired by an anime character.

Image caption: Alex Yu's mask is inspired by an anime character

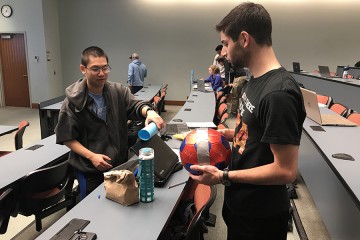

And others did the best that they could despite their limited artistic abilities. Stan Chu, a second-year student double majoring in molecular and cellular biology and political science, laughs when he displays his mask, which resembles a Mexican luchador wrestler. It didn't turn out how he had planned, he says, but he still he sees it as a win.

"The hands-on approach to this class was really conducive to actually learning the techniques," Chu says. "This was one of the most enjoyable classes I've taken so far."

If Premo could change anything about the class, she would expand the studio space, invest in more tools, and open it up to more students.

"I always have a waitlist for my classes," she says. "Usually it's about 20 students, but I've had as many as 45 students trying to get in. My two loves are medicine and being an artist, and I wish I could share that with more students."

Student masks are now on display in the Ross Jones building of the Mattin Center on the Homewood campus.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged homewood arts programs, intersession, center for visual arts